FCPA Winter Review 2021

International Alert

Introduction

2020: Year in Review

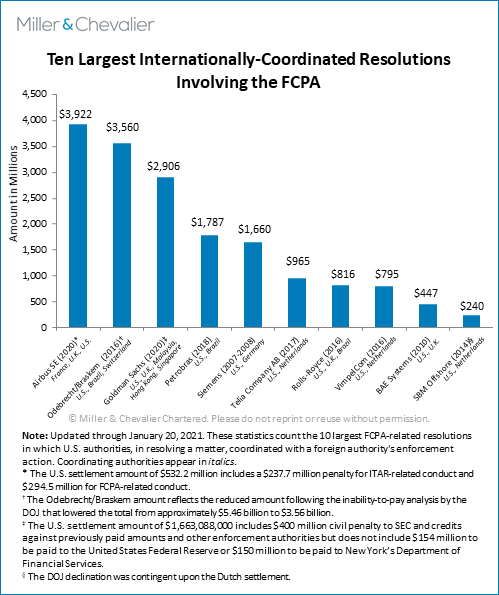

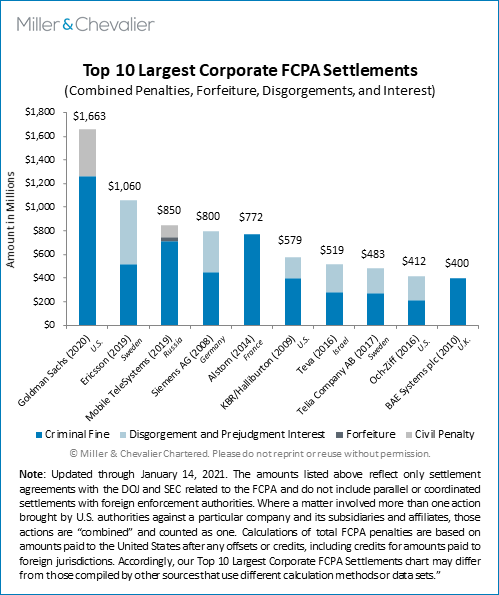

Calendar year 2020 saw a decline in the number of announced enforcement actions related to the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA), in part due to the effects of the global COVID-19 pandemic. That said, 2020 also saw new FCPA enforcement records set by the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) and Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Specifically, the January 2020 Airbus disposition involved almost $4 billion in fines and disgorgement shared among the enforcement agencies of the U.S., France, and the U.K. and was the largest internationally-coordinated matter involving the FCPA to date (though a substantial amount of the penalties resulted from export control violations). Later, the October 2020 resolution of DOJ and SEC investigations of Goldman Sachs (involving $2.3 billion in penalties and fines and $606 million in disgorgement, reduced to $1.663 billion total paid to the DOJ and SEC after allowing offsets for amounts paid to other regulators) was the largest-ever settlement under the FCPA itself, based on amounts actually collected by the U.S. government. The Goldman Sachs disposition broke the record-setting resolutions that U.S. authorities entered into in 2019 with the telecommunications companies Telefonaktiebolaget LM Ericsson and PJSC Mobile TeleSystems. Moreover, although the DOJ and SEC did allow offsets for amounts paid in Brazil, the DOJ and SEC resolutions in 2020 with J&F Investimentos and its subsidiary JBS were not coordinated with the Brazilian authorities – which reached a leniency agreement with J&F in 2017. But if the resolutions had been coordinated, the combined amount would easily qualify for the top 10 list below, with a grand total potentially above $3 billion, depending on the exchange rate used in calculating the total fines.

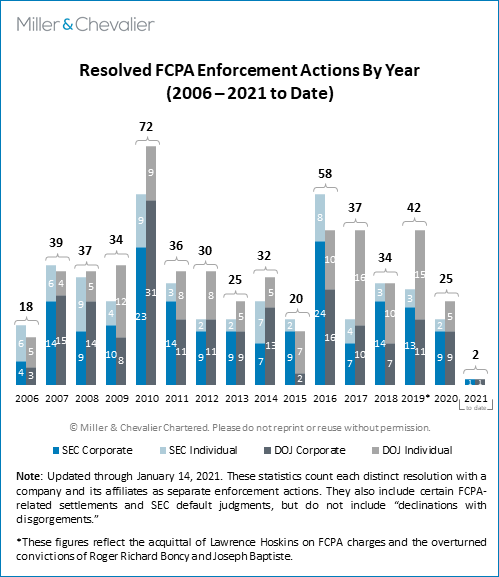

Overall, the DOJ resolved nine cases against companies and three actions against individuals in 2020, while the SEC concluded nine settlements with companies and two actions related to individuals. As usual, the DOJ and SEC enforcement activity overlapped to some extent, with a net total of 14 companies (counting subsidiaries or affiliates as one company for this purpose) concluding FCPA resolutions. The total number of 25 resolved FCPA enforcement actions by the DOJ and SEC in 2020 was more than 43 percent lower than the 2019 total of 44 resolutions and is tied with the year 2013 as the year with the second lowest total since 2007 — only 2015, in which 20 FCPA enforcement actions were publicly announced, had fewer concluded cases.

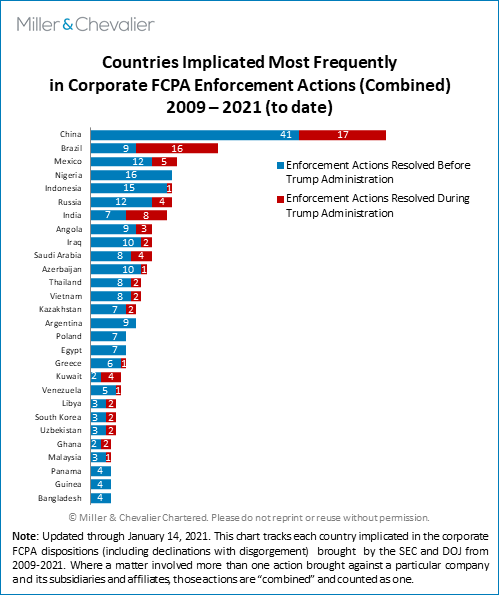

Regarding countries implicated most frequently in corporate FCPA enforcement actions, China and Brazil remain at the top in the spotlight, with China implicated in 17 enforcement actions and Brazil in 16 under the Trump administration. In 2020, the resolutions with Airbus, Novartis, Herbalife Nutrition, and Cardinal Health all involved alleged misconduct in China, while Brazil seems to have been the focus of the resolutions in the second half of the year, with Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Sargeant Marine, J&F Investimentos and its Brazilian subsidiary JBS, and Vitol all reaching settlements with the U.S. authorities related to issues in Brazil. As indicated in the chart below, India is the third most frequently implicated country, which was involved in a total of eight enforcement actions in the past four years (including one case resolved in 2020 – Beam Suntory), and Mexico (five enforcement actions) and Saudi Arabia (four enforcement actions) took the fourth and fifth places.

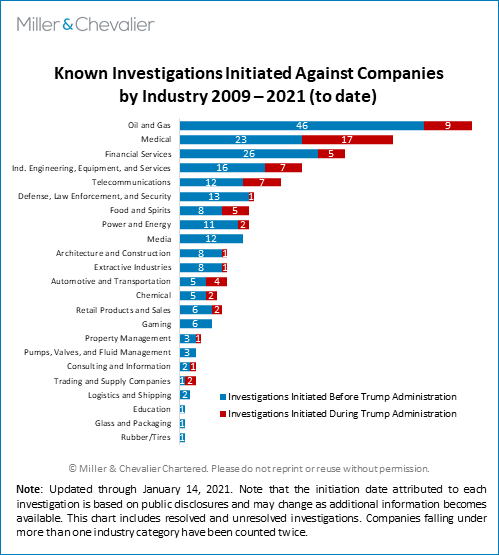

The following chart provides an update on known FCPA investigations initiated against companies by industry over the past 10 years. Certain industries have historically attracted and continue to attract FCPA enforcement attention, partly due to the inherent risks in sectors with heavy government regulation or nature of the transactions and partly due to the nature of the investigations, which often focus on multiple companies implicated in the same or similar conduct. The Trump administration initiated a total of 17 publicly disclosed enforcement actions against companies in the medical industry, which nearly doubled the number of cases in the runner-up industry—oil and gas (nine enforcement actions). The telecommunications industry and the industrial engineering, equipment, and services industry tied for third place, each facing seven enforcement actions under the Trump administration, with the fourth place claimed by the financial services industry and the food and spirits industry, each facing five enforcement actions. The 2020 resolutions show general consistency with this overall pattern, with actions involving the financial sector (Goldman Sachs, J&F Investimentos, and World Acceptance Corporation), the medical industry (Novartis, Alcon PTE, and Cardinal Health), the energy sector (Eni and Vitol), and the food and spirits industry (Herbalife Nutrition, Beam, and JBS).

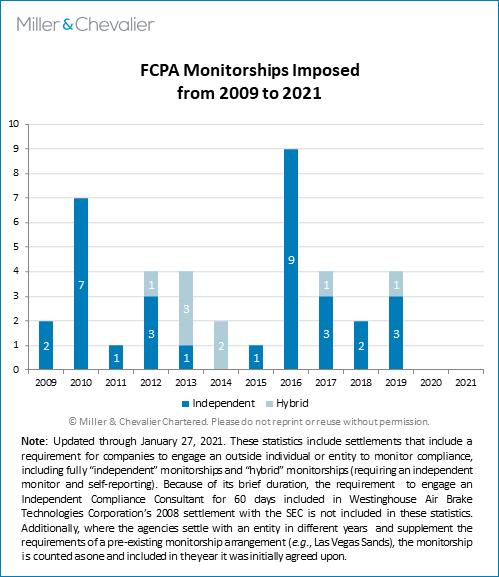

A couple of other trends on the corporate enforcement side are worth noting. First, 2020 was the first year in a decade in which the U.S. authorities did not impose an independent compliance monitor in a corporate settlement. A caveat to this statement is that Airbus accepted auditing and supervision of its compliance program by France's AFA for a term of three years, a fact specifically cited by the DOJ in its determination that a U.S.-appointed monitor was "unnecessary." The U.K. Approved Judgement also noted that Airbus had already established a three-member Independent Compliance Review Panel "to complete an independent review of Airbus' ethics and compliance procedures," issuing reports in 2018 (with 55 recommendations) and 2019, with a third report expected in 2020. Similarly, the DOJ did not impose a compliance monitor for J&F Investimentos in part because the entity has its compliance program audited annually by an independent entity. That said, the last U.S.-imposed independent compliance monitorship occurred in the December 2019 Ericsson disposition.

There are likely several reasons for this trend. First, as stated in various 2020 resolutions, the agencies have considered compliance program remediation efforts undertaken by the companies under investigation prior to the disposition and found them to be sufficient in light of the circumstances at issue. The FCPA Corporate Enforcement Policy highlights the importance of remediation as a mitigating factor in case outcomes – including the need for companies to be able to show the DOJ data on the effectiveness on program upgrades – and companies appear to have responded to this imperative as expected. This trend may also reflect the effects of the October 2018 DOJ monitor policy issued by then-Assistant Attorney General Brian Benczkowski, which focused in part on the costs of monitorships – not only monetary costs but also whether the "proposed scope of a monitor's role is appropriately tailored to avoid unnecessary burdens to the business's operations." The policy instructs DOJ attorneys to favor the imposition of a monitor only in cases where there is a "demonstrated need for, and clear benefit to be derived from, a monitorship relative to the potential costs and burdens." Despite some 2020 cases in which the public documents detail significant breakdowns in compliance program elements, related internal accounting controls, or support for compliance by senior management, ultimately the DOJ found no such demonstrated need for a monitor, usually insisting instead on company self-evaluation and reporting. One question going forward is whether the new administration follows the same path.

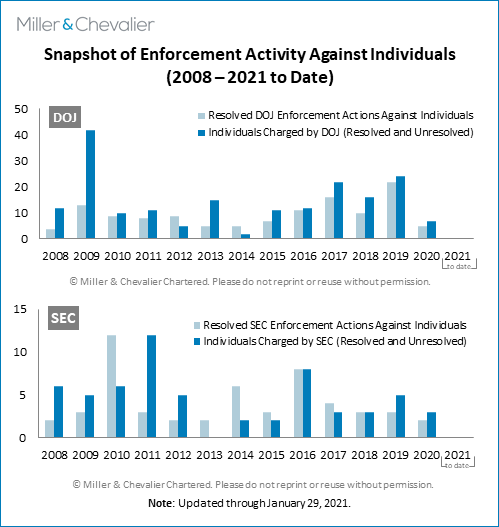

Despite public statements reaffirming the commitment of both agencies to the pursuit of culpable individuals, the number of publicly announced resolutions against individuals was substantially below 2019 levels and levels for the last few years. The chart below shows that this decline was precipitous for the DOJ, while the SEC levels were more in line with past years – though such levels are generally lower than the DOJ numbers. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic likely weigh heavier here than on corporate actions, since most cases involving individuals require extensive court-based activities, which have been substantially curtailed for much of 2020. The agencies certainly continue stating publicly that they remain committed to enforcement actions against individuals, and it is likely that the numbers will start to bear this out as pandemic issues that interfere with such cases continue to be addressed in various ways.

In 2020, the DOJ and SEC resolved seven FCPA enforcement actions against individuals (five by the DOJ and two by the SEC). In January 2020, Armengol Alfonso Cevallos Diaz, an Ecuadorian businessman based in Miami, pleaded guilty to one count of conspiracy to violate the FCPA and one count of conspiracy to commit money laundering. In February 2020, Tulio Anibal Farias-Perez, a Venezuelan citizen and U.S. resident, pleaded guilty to one count of conspiracy to violate the FCPA. In September 2020, Sargeant Marine had pleaded guilty and agreed to pay more than $16 million in criminal fines to resolve FCPA charges. In December 2020, Jorge Luz and his son Bruno Luz, who worked as third-party intermediaries on behalf of Sargeant Marine, each pleaded guilty to one count of conspiracy to violate the FCPA. Also in December 2020, Deck Won Kang, a U.S. citizen based in New Jersey, pleaded guilty to an information charging him with violating the anti-bribery provision of the FCPA. On the SEC side, Brazilian nationals Joesley Batista and Wesley Batista and their companies J&F Investimentos S.A. and JBS S.A. reached a settlement with the SEC in October 2020 to resolve their bribery charges, whereby JBS agreed to pay approximately $27 million in disgorgement and the Batistas each agreed to pay a civil penalty of $550,000. J&F also pleaded guilty to conspiracy to violate the FCPA and agreed to pay a criminal penalty of over $256 million.

As noted in earlier Reviews, the U.S. authorities announced several important policy developments in 2020. These included, among others, the June 1, 2020 update by the DOJ of its guidance on Evaluation of Corporate Compliance Programs, the July 3, 2020 publication by the DOJ and SEC of a long-awaited "Second Edition" update to the FCPA Resource Guide, and the August 14, 2020 release by the DOJ of its first FCPA Opinion Procedure Release since November 2014 in response to a request from a multinational investment advisor firm.

Further, U.S. courts issued several key FCPA-related rulings in 2020, with mixed results for U.S. authorities. Most notably, in Liu v. SEC, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld – but limited – the SEC's authority to seek the equitable remedy of disgorgement – though the National Defense Authorization Act passed by Congress on January 1, 2021 contained provisions addressing that decision, as discussed below. In December 2020, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit affirmed a lower court's 2018 jury conviction of Hong Kong businessman and former government official, Patrick Ho, on several FCPA and money laundering charges. On the other hand, the U.S. District Court for the District of Connecticut granted Lawrence Hoskins' motion for acquittal and conditionally granted Hoskins motion for a new trial on the FCPA charges in February 2020, although the court denied Hoskins' motions for acquittal and a new trial on the conviction of three substantive money laundering violations. Hoskins is a former Senior Vice President at Alstom, S.A., who was convicted of six substantive FCPA violations, three substantive money laundering violations, and two conspiracy violations. Similarly, the U.S. District Court for the District of Massachusetts in March 2020 tossed out the convictions of Joseph Baptiste and Roger Richard Boncy, who were previously found guilty of corruption charges arising out of an investigation into allegations of solicitation of bribes in connection with a port development project in Haiti, and ordered a new trial for both Baptiste and Boncy.

International anti-corruption enforcement actions and multilateral cooperation efforts continued in 2020. For example, the year kicked off with authorities in the United States, the United Kingdom, and France announcing the settlement with Airbus, which agreed to pay almost $4 billion in combined global penalties to resolve allegations of bribing government officials and non-governmental airline executives in exchange for lucrative business deals. In February 2020, the Sanctions Committee of the French Anti-Corruption Agency (AFA) found for the first time that a French company, Imerys S.A., had failed to comply with the compliance requirements articulated in Sapin II—France's anti-corruption law—though the committee declined to impose any penalties requested by the AFA. In July 2020, a Malaysian court found former Malaysian prime minister Najib Razak guilty of seven counts of abuse of power, money laundering, and breach of trust, related to the 1MDB scandal, sentenced Mr. Najib to 12 years in prison, and issued him a fine of nearly $50 million dollars.

On the international policy front, major developments include, among others, the U.K. Serious Fraud Office's (SFO) issuance of guidance on evaluating the effectiveness of companies' compliance programs on January 17, 2020 and an update by the SFO of its Operational Handbook with guidance on SFO's approach to deferred prosecution agreements (DPAs) on October 23, 2020; AFA's publication of its Annual Activity Report that highlights its guidance and monitoring activities during 2019; the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)'s issuance of its Phase 4 Report of the United States, commenting on U.S. enforcement of the FCPA and compliance with OECD treaty obligations; and China's establishment of the National Supervisory Commission—the highest-ranked anti-corruption agency in the country.

Q4 2020

The fourth quarter of 2020 continued the third quarter's trend of greater activity by U.S. enforcement authorities after an unusually quiet first half of 2020 (which was driven in large part by the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic). The quarter saw the announcement of four enforcement actions against companies (J&F Investimentos, Goldman Sachs, Beam Suntory, and Vitol). Two of those actions (J&F Investimentos and Goldman Sachs) included significant monetary penalties, with Goldman Sachs taking the title of the largest corporate FCPA resolution with the DOJ and SEC based on the net amounts paid to the U.S. government under the resolution. The Goldman disposition was also the third largest internationally coordinated set of resolutions ever, behind the cases involving Airbus in early 2020 and Odebrecht/Braskem in 2016. The fourth quarter also saw the U.S. Commodities Future Trading Commission (CFTC) resolving its first foreign bribery case (related to Vitol) since the agency's announcement in March 2019 of its intention to have foreign bribery be subject to enforcement actions brought by the CFTC. Among the disposition of other investigations, the Goldman case also included a resolution with the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank that also covered bribery-related issues and compliance program remediation obligations. In addition, the DOJ announced enforcement actions against three individuals in the last quarter of 2020 – all of which involved guilty pleas. Meanwhile, the SEC resolved two corporate enforcement actions (against J&F Investimentos and Goldman Sachs) as well as dispositions involving two individuals in connection with the J&F Investimentos matter. There was also one FCPA-related sentencing in the last quarter of 2020.

The fourth quarter of 2020 also witnessed several significant policy, litigation, and international developments, including a notable appellate decision in an FCPA case that, among other important aspects, addressed several FCPA-related issues for the first time in a precedential case and demonstrated the expansive jurisdictional reach of the anti-money laundering laws; a dissent by two SEC Commissioners from what they characterized as an "unduly broad view" of the FCPA's internal accounting controls provision by the SEC's enforcement arm; the issuance by the OECD Working Group on Bribery of the final Phase 4 report on the United States; and the issuance of SFO's guidance on disclosures/DPAs.

We summarize this quarter's corporate enforcement actions, individual enforcement actions, and other policy, litigation, and international developments below.

Corporate Enforcement Actions

J&F Investimentos. On October 14, 2020, J&F Investimentos (J&F), a Brazilian investment company with operations in the meat and agriculture industry, pleaded guilty to one count of conspiring to violate the anti-bribery provisions of the FCPA and agreed to a criminal monetary penalty of more than $256 million. The company admitted to paying tens of millions of dollars in bribes to government officials in Brazil in order to ensure that Brazilian state-owned and state-controlled banks would enter into debt and equity financing transactions with the company and its affiliates or approve corporate acquisitions. The disposition documents state that up to half of the $256 million in criminal fines that J&F agreed to in connection with the plea agreement with the DOJ would be offset against penalties that the company would pay to Brazilian authorities in connection with the same misconduct and as part of J&F's leniency agreement with them. As we noted in our FCPA Summer Review 2017, J&F previously reached an agreement with the Brazilian authorities and – according to the DOJ agreement – agreed to pay a criminal fine of more than R$8 billion and to contribute to social projects for approximately R$2.3 billion. (At the time, this amounted to a total resolution of approximately $3.2 billion; because the Real has weakened vis-à-vis the US dollar, the DOJ noted that the current amount is approximately $1.8 billion.) On the same day, the SEC announced that J&F settled a related action with the SEC, pursuant to which JBS, a company controlled by J&F, agreed to pay $27 million in disgorgement -- thus bringing the total U.S.-related corporate sanctions for J&F to approximately $156 million after accounting for the $128 million paid to the Brazilian authorities.

Goldman Sachs. On October 22, 2020, the DOJ announced that Goldman Sachs, a global investment bank and financial services company headquartered in New York City, had entered into a $1.66 billion FCPA settlement with the DOJ in connection with an illicit payments scheme, in which $3.5 billion was misappropriated from 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB), a Malaysian state-owned fund for investment and development of projects that was "established to drive strategic initiatives for the long-term economic development of Malaysia." As part of the resolution, Goldman Sachs Group, Inc., the parent company of Goldman Sachs, entered into a DPA with the DOJ and agreed to approximately $2.3 billion in criminal penalties. According to DOJ's press release and the DPA, between approximately 2009 and 2014, Goldman Sachs conspired with others to violate the anti-bribery provisions of the FCPA by engaging in a scheme to pay more than $1.6 billion in bribes to government officials in Malaysia and Abu Dhabi in order to obtain and retain business for Goldman Sachs from 1MDB, including securing the company's advisory role on energy acquisitions, as underwriter on three bond deals worth $6.5 billion, and a potential role in a lucrative IPO for 1MDB's energy assets. In a related case, Goldman Sachs's Malaysian subsidiary, Goldman Sachs (Malaysia) Sdn. Bhd., pleaded guilty to one count of conspiracy to violate the anti-bribery provisions of the FCPA and was fined with a criminal penalty of $500,000.

On the same day, the SEC announced that Goldman Sachs had settled a related enforcement action with the agency. The SEC's Cease-and-Desist Order found that Goldman Sachs violated the anti-bribery, internal accounting controls, and books and records provisions of the FCPA in relation to the conduct also discussed in the DOJ documentation. Pursuant to the Order, Goldman Sachs agreed to pay civil monetary penalty of $400 million and disgorgement of approximately $606.3 million.

As we have reported in past FCPA Reviews (here and here, for example), the funds raised by 1MDB were allegedly misappropriated by intermediaries, including the financier Jho Low, and two of the bank's managing directors at the time, Ng Chong Hwa and Tim Leissner. As we previously reported in our FCPA Spring Review 2020, Leissner, a former Southeast Asia Chairman and Managing Director of Goldman Sachs, pleaded guilty to conspiracy to violate the FCPA and conspiracy to commit money laundering. Ng Chong Hwa, known as "Roger Ng," a former Managing Director of Goldman Sachs and Head of Investment Banking for GS Malaysia, was charged with conspiracy to violate the FCPA and conspiracy to commit money laundering; Ng is fighting the charges in court.

In parallel actions in several other countries arising from the same conduct, Goldman Sachs agreed to pay $126 million, $122 million, and $350 million to the authorities of U.K., Singapore, and Hong Kong, respectively. In addition, the company agreed to pay $150 million to New York state investigators and $154 million to the U.S. Federal Reserve. The DPA and other documents note that the DOJ took action to credit payments to these other agencies (and the SEC) in its penalty payment requirements.

Beam Suntory. On October 27, 2020, the DOJ announced that Beam Suntory Inc., a Chicago -based producer of distilled beverages and subsidiary of Suntory Holdings of Osaka, Japan, agreed to resolve the Department's FCPA investigation by entering into a three-year DPA and paying a criminal monetary penalty of approximately $20 million. According to the DOJ, Beam Suntory bribed Indian government officials from 2006 to 2012, mostly through third-party promotors and distributors, to obtain business at government-controlled depots and stores. DOJ's investigation into Beam Suntory arose from the same conduct covered in the SEC's resolution with the company in July 2018, when the company had agreed to pay approximately $8.2 million (approximately $5.3 in disgorgement, approximately $918,000 in prejudgment interest, and $2 million in civil penalty) to settle civil charges arising from improper payments made by the company's Indian subsidiary. Specifically, according to the SEC's Cease-and-Desist Order, between 2006 and 2012, Beam Suntory's Indian subsidiary used third-party sales promoters and distributors to make improper payments to government employees in order to boost sales orders, process license and label registrations, and facilitate the company's distilled spirit products.

Vitol Inc. On December 3, 2020, the DOJ announced that Vitol Inc., the U.S. affiliate of Geneva-based Vitol Group, one of the largest energy trading firms in the world, agreed to enter into a DPA to settle two charges that it had conspired to violate the anti-bribery provisions of the FCPA by bribing foreign officials in Brazil, Ecuador, and Mexico in order to win contracts with state-owned companies in the oil and gas sector in the three countries. According to the DOJ, Vitol entered into sham consulting arrangements through shell companies and created fake invoices to pay bribes to foreign officials. Vitol agreed to a criminal penalty of $135 million to resolve the DOJ's investigation, and the DOJ agreed to credit $45 million that the company will pay to the Brazilian authorities.

In a related settlement with the CFTC on the same day, Vitol agreed to a civil penalty and disgorgement of more than $95 million to resolve allegations that the alleged bribery defrauded the company's counterparties and harmed other market participants, among others. Taking into account that the criminal penalty to the DOJ will offset a portion of the penalty paid to the CFTC, Vitol's final monetary penalty to CFTC includes disgorgement of approximately $12.8 million and a civil penalty of $16 million, thus bringing the total cost of Vitol's settlement with the U.S. authorities to approximately $118.8 million after accounting for the $45 million to be paid to the Brazilian authorities. This is CFTC's first resolution of a foreign bribery case.

A common feature of all of the DOJ corporate resolutions in this quarter is a new Attachment E, styled as a DPA or plea agreement disclosure certification. These certification requirements reinforce the disclosure requirements that have been a feature of DOJ FCPA dispositions for several years. Such requirements vary, but generally require covered companies to disclose to the DOJ "any evidence or any allegations of conduct that may constitute a violation of the FCPA anti-bribery provisions had the conduct occurred within the jurisdiction of the United States" – language that can cover a potentially broad swathe of information that goes well beyond actual evidence of illegal conduct. The certifications require sign-off by the company's CEO and CFO – in an echo of the Sarbanes-Oxley 302 certifications – and reiterate the importance of such disclosures to the DOJ's consideration of whether a company has complied with the DPA or plea agreement requirements. Such certifications now appear to be standard practice going forward.

The reasons behind these more formal certification requirements have not been expressly stated by the DOJ; in our experience, such changes often are driven by DOJ policy goals or experiences with similar past agreements that reveal an issue or problem that existing agreement terms did not fully address. The addition of the certification language when the DPA is signed does remove any uncertainty at the end of the DPA term on the exact language to be used in the relevant certifications, thereby avoiding any last minute negotiations or surprises for either the DOJ or the corporate entities. This might well be a key reason for the change. If the DOJ continues to impose such certifications, affected companies likely will have to develop methodologies to support the CEO/CFO sign-off, such as sub-certifications or other confirmation processes – again, potentially similar to processes developed in the Sarbanes-Oxley space.

Individual Enforcement Actions

As mentioned above, the DOJ brought two enforcement actions against three individuals in the fourth quarter that concluded with guilty pleas. The SEC resolved an enforcement action against two individuals in connection with its corporate FCPA resolution with J&F Investimentos.

On October 14, 2020, the SEC found that Joesley Batista and Wesley Batista, two Brazilian nationals and J&F executives, caused violations of the books and records and internal controls provisions of the FCPA. Each individual agreed to pay a civil penalty of $550,000, undergo enhanced ethics and FCPA training, and submit annual certifications of completion to resolve the matter. Joesley Batista has been a long-standing focus of the Lava Jato (Operation Car Wash) for alleged bribes made by his company JBS S.A. to Eduardo Cuhna, the former president of the Brazilian parliament. As we reported in our FCPA Summer Review 2017, Batista had turned over to Brazilian authorities a March 2017 recording, in which Brazil's then-President Michel Temer purportedly assented to Batista paying bribes to Cuhna to prevent him from cooperating with Brazilian authorities. Notwithstanding his cooperation, the press reported that he was arrested later that year after his attorneys inadvertently provided prosecutors with a recording in which he stated that he had not provided all the evidence he held regarding corruption, contrary to the cooperation agreement that he had negotiated.

On December 10, 2020, Jorge Luz and his son Bruno Luz, who worked as third-party intermediaries on behalf of Sargeant Marine, each pleaded guilty to one count of conspiracy to violate the FCPA. As we reported in out FCPA Autumn Review 2020, Sargeant Marine Inc. pleaded guilty and agreed to pay more than $16 million in criminal fines to resolved FCPA charges. The DOJ had charged Jorge Luz and Bruno Luz with conspiracy to violate the FCPA the previous day, December 9, 2020. Jorge Luiz and his son were sentenced in Brazil to five years each for their role in arranging over $5 million in bribes to be paid by Sargeant Marine to Petrobras officials and are currently awaiting sentencing in the United States.

On December 17, 2020, the DOJ announced that Deck Won Kang pleaded guilty during a court videoconference to violating the anti-bribery provisions of the FCPA by paying $100,000 to a South Korean naval official. According to the Information, Kang, a U.S. citizen with primary residence in New Jersey, owned two companies that provided naval equipment and technology services. Between April 2012 and February 2013, Kang apparently sought to secure contracts with South Korea's Ministry of National Defense by making eight payments to a high ranking South Korean official in exchange for assistance with obtaining the contracts. Kang is currently awaiting sentencing.

On October 28, 2020, Mark Lambert, a former executive at Transportation Logistics International Inc. (TLI), was sentenced to a four-year prison term for paying $1.5 million in bribes to a Russian official at a subsidiary of a Russian state-owned entity. The sentence came almost two years after Lambert had been indicted on bribery, fraud, and money laundering charges in January 2018. As we previously reported in our FCPA Spring Review 2018, TLI reached its own FCPA-related DPA with the DOJ and agreed to pay a $2 million penalty in March 2018.

Lastly, although not counted towards our statistics for the last quarter of 2020, we report that the in the fourth quarter DOJ unsealed charges against Rodrigo Garcia Berkowitz, a Houston-based former Petrobras official, who received bribes in association with the Vitol bribery scheme. On February 8, 2019, Mr. Berkowitz had pleaded guilty to one count of conspiracy to commit money laundering. In addition, the DOJ unsealed charges against Luiz Eduardo Andrade, one of the intermediaries involved in the Brazil scheme, who had pleaded guilty on September 22, 2017 to one count of conspiracy to violate the FCPA in connection with a related bribery scheme. As we reported in our FCPA Autumn Review 2020, on September 22, 2020, Sargeant Marine, a Florida-based company that once operated a JV with Vitol, pleaded guilty to working with Andrade and others to bribe officials in Brazil, Ecuador, and Venezuela to win asphalt contracts. Berkowitz and Andrade were arrested in the United States in December 2018 as part of Operation Car Wash. Both individuals are awaiting sentencing.

Policy & Litigation Developments

The fourth quarter of 2020 also included several important policy and litigation developments, including the following.

On November 13, 2020, SEC Commissioners Hester Peirce and Elad Roisman issued a public dissent to the SEC's settlement in the matter of Andeavor LLC in which the company was ordered to pay a $20 million civil penalty. According to the dissent, the SEC had employed an "unduly broad view" of the FCPA's internal accounting controls provisions, although the investigation itself did not involve foreign bribery. A majority of the Commission had found that Andeavor had violated this provision when it used an "abbreviated and informal process" to evaluate the materiality of the company's acquisition by Marathon Petroleum Corporation yet went ahead and repurchased its stock after it had concluded that it did not possess material non-public information about the merger. In contrast, Commissioners Peirce and Roisman disagreed with the Commission's interpretation of the internal accounting controls provisions, which they noted "seem primarily to concern the accounting for a public company's assets and transactions to ensure that its financial statements are prepared in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles," to cover "internal controls" more broadly. This perspective is consistent with critiques by some compliance experts of the SEC's incorporation of elements such as employee training programs into the definition of "internal accounting controls" in past FCPA settlements. Whether this narrower reading influences the Commission's views more generally, especially under the new U.S. administration, remains to be seen.

On December 29, 2020, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, in an opinion that addressed several issues of first impression under the FCPA, affirmed the conviction and sentence of Chi Ping Patrick Ho for bribing foreign officials in Chad and Uganda. In December 2019, Ho, who was an officer and director of a U.S.-based non-governmental organization (NGO) funded by a Chinese company, had been found guilty of money laundering and violating and conspiracy to violate the FCPA's anti-bribery provisions. In March 2019, Ho was sentenced to three years in prison. Ho had challenged his convictions, arguing that he had not acted on behalf of a "domestic concern." Ho further argued that he could not be charged under the "mutually exclusive," according to him, domestic concern and territorial jurisdiction provisions of the FCPA. The Second Circuit rejected Ho's arguments and affirmed his convictions.

Finally, we note that the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2021 (NDAA) passed on January 1, 2021 clarified that the federal courts now have statutory authority to order disgorgement – and other remedies based in equity – for violations of federal securities laws, including the FCPA, and in certain cases the courts can do so for a period of up to 10 years from the latest date of a violation. These statutory provisions are in part a response to the Supreme Court holdings in the Kokesh and Liu cases. For further discussion of these provisions, please see this article by Miller & Chevalier attorneys Ann Sultan, Margot Laporte, and Paul Leder. The NDAA also included the new Corporate Transparency Act, which is discussed in our latest update on Money Laundering Enforcement Trends for Winter 2021.

We discuss the noteworthy policy and litigation developments in more detail below.

International Developments

There were several significant international developments during the last quarter of 2020.

In the United Kingdom, on October 23, 2020, the SFO published its new comprehensive internal guidance on how it approaches deferred prosecution agreements and engages with companies under investigation where a DPA is a "prospective outcome." The guidance outlines a process for the SFO to determine if a DPA is appropriate, discusses the requirements for companies to petition for a DPA, and highlights the importance for companies of self-reporting and open communication and continued cooperation with the SFO.

On October 30, 2020, the SFO announced that it has entered into a DPA with Airline Services Ltd. (ASL). This is SFO's ninth DPA since 2014 and the third in 2020 alone, according to the SFO. According to the terms of the DPA, ASL accepted responsibility for three counts of failing to prevent bribery arising from the company's use of an agent to secure contracts worth more than £7.3 million to refurbish commercial aircraft for Lufthansa. As part of the resolution with the SFO, ASL agreed to pay approximately £3 million: £1.2 million in financial penalty, approximately £1 million in disgorgement, and £750,000 to cover SFO's costs.

On November 17, 2020, the OECD Working Group on Bribery released to the public its final Phase 4 report on the United States' implementation of the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention. The report, which is part of OECD Working Group's ongoing monitoring process, focuses primarily on the United States' enforcement of the FCPA and highlights the country's foreign bribery enforcement efforts since 2010, the date of the OECD Working Group's Phase 3 report. The report generally paints a positive picture of U.S. enforcement trends, though the Working Group did advance several recommendations and noted some concerns with certain U.S. court decisions.

In Brazil, the fourth quarter of 2020 witnessed the end of Operation Car Wash, a global investigation into alleged improper payments to Petrobras personnel and high-ranking politicians and government officials from Brazilian state-owned or -controlled entities and which included non-Brazilian companies and led to criminal indictments of more than one thousand individuals.

We discuss these and other international developments in more detail below.

Corporate Enforcement Actions

Brazilian Investment Company Pleads Guilty, Resolves Criminal Foreign Bribery Charges

J&F Investimentos S.A. (J&F) and its owners Joesley and Wesley Batista have been central figures in the anti-corruption landscape in Brazil for many years. The company and the Batista brothers have been the subject of numerous investigations, enforcement actions, and cooperation agreements in Brazil. On October 14, 2020, J&F reached concurrent resolutions with both the DOJ and SEC (with the SEC resolution also covering the Batista brothers themselves and a J&F subsidiary), concluding another key chapter in the J&F saga.

Specifically, on October 14, 2020 the DOJ announced that J&F had pleaded guilty to conspiracy to violate the anti-bribery provisions of the FCPA and agreed to a criminal monetary penalty of $256,497,026 to resolve the matter, although the DOJ has reduced the amount based on J&F's payments to the authorities in Brazil, as summarized below. The DOJ detailed three different bribery schemes within the criminal Information and related plea agreement filed in the Eastern District of New York (EDNY): (1) payments to Brazilian officials related to the financing via Banco Nacional de Desenvolvimento Econômico e Social (BNDES) for J&F's acquisition of Pilgrim's Pride Corporation (Pilgrims), an issuer headquartered in the United States; (2) payments to facilitate a merger approval by Fundação Petrobras de Seguridade Social (Petros); and (3) payments to acquire financing from Caixa Econômica Federal (Caixa), a state-owned bank in Brazil. The DOJ Information explained that J&F used intermediaries to assist in paying bribes to the public officials (and that J&F Executive 1, almost certainly Joesley Batista based on publicly-available materials, also made payments to government officials as an intermediary on behalf of other companies). The DOJ detailed that the schemes involved shell companies incorporated in the United States as well as bank accounts and real estate in New York; the DOJ also noted that key personnel held meetings in the United States to discuss the improper payments.

First, the DOJ explained that during 2005 to 2014, J&F paid bribes to Brazilian officials to help ensure that BNDES would agree to financing and equity transactions for entities associated with J&F. In furtherance of the scheme, J&F used New York-based accounts to help pay over $148 million in bribes to high-level government officials in Brazil. J&F and its executives established accounts for shell companies created in the US and used the accounts to fund bribes to Brazilian public officials. Second, from 2011 to 2017, J&F paid over $4.6 million in bribes to Brazilian officials at Petros, a state-controlled pension fund. The bribes were paid in order to obtain approval from Petros for a merger that J&F wished to be granted. Related to this scheme, J&F and its executives purchased an apartment in New York City and transferred the apartment to a Brazilian official. Third, in order to obtain financing from Caixa, a Brazilian controlled bank, J&F used its bribery system to pay $25 million to a public official in the Brazilian legislative branch. The bribes were paid from 2011 to 2014, to ensure certain financing for J&F from Caixa. In addition, the illicit payments made under this scheme were discussed by J&F executives while in the US.

To resolve the DOJ charges stemming from the bribery scheme, J&F entered into a plea agreement with the agency which included among other things, a commitment to enhance its compliance program and to pay the criminal monetary penalty. In turn, the penalty was reduced by 10 percent due to the company receiving partial credit from the DOJ for remediation and cooperation with the agency. The DOJ explained that J&F did not receive full cooperation credit because "among other things, [J&F] initially declined to produce all relevant materials and failed to produce all relevant documents and information in a timely manner." With respect to the plea agreement, the DOJ also noted that it took into consideration the company's failure to voluntarily disclose the illicit activity and drew attention to the involvement of executives "at the highest level" and that bribes were paid to high-ranking officials over several years.

In a related action, the SEC also brought FCPA charges against J&F, JBS S.A. (JBS), and the Batista brothers. JBS is a Brazilian subsidiary of J&F that is publicly traded in Brazil and has over-the-counter share sales in the US. The SEC announced on October 14, 2020, that JBS agreed to pay approximately $26.9 million in disgorgement and that Joesley Batista and Wesley Batista each agreed to pay civil penalties of $550,000 to the SEC. With respect to J&F and JBS, the SEC did not impose a civil penalty in light of the resolution J&F had entered into with DOJ.

The SEC Order stated that the Batistas orchestrated a bribery scheme in order to assist JBS in its acquisition of Pilgrims in December 2009. Pilgrims was under Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection at the time. The bribery scheme entailed the Batistas paying bribes to Brazilian foreign officials, including the Brazilian Finance Minister, from 2009 to 2015 (after the acquisition), totaling approximately $150 million. In turn, the Finance Minister assisted the Batistas and JBS in securing $2 billion in equity financing from BNDES, which the Batistas used to assist JBS with the purchase of Pilgrims. Once Pilgrims was acquired, the Batistas joined the board of Pilgrims, and Pilgrims exited bankruptcy. While on the Board, the Batistas engaged in the bribery scheme unbeknownst to Pilgrims management. Among other things, the SEC maintained that JBS accounts were commingled with funds from Pilgrims obtained through certain intercompany transfers, and these funds were in turn used to pay bribes. However, the use of the funds for such bribes was not reflected in Pilgrims books and records. According to the agency, the illicit activity occurred between 2009 through 2015, all without the knowledge of Pilgrims management. As part of the Batistas' scheme to hide the bribes, Pilgrims and JBS shared management and systems – including "sharing the same senior officers and other key management positions" as well as the "accounting and SAP systems" and JBS policies. Consequently, Pilgrims books and records reflected false information regarding the transfers and payments. Further, during due diligence and audits, the Batistas failed to inform Pilgrims' accountants that funds transferred to JBS had been commingled with funds that were used for illegal payments to public officials. Under the Order, the SEC found that J&F, JBS, and the Batistas caused Pilgrims to violate the FCPA's books and records and internal accounting controls provisions.

Notably, in reaching its conclusion the agency stated that Pilgrims failed to enact its own code of conduct until 2015, which was several years after having been acquired. Moreover, Pilgrims was still in the process of establishing an anti-bribery and compliance program nearly nine years after its acquisition. Per the order, the Batistas also did not receive any anti-bribery training, made Pilgrims rely on JBS's code of ethics, SAP system, and policies, and knowingly caused Pilgrims to reflect false books and records. The SEC noted that the Batistas did not disclose their participation in the bribery scheme until 2017. As part of a leniency agreement with the Brazilian government, the Batistas agreed not to serve as a board member on a publicly traded company, and both resigned from the Board of Pilgrims. Pursuant to the SEC order, J&F, JBS, and the Batistas agreed to comply with a three-year requirement to self-report on remedial actions they will take, including implementing an integrity program and reporting on the effectiveness of compliance policies and internal accounting controls, among other things. The Batistas also agreed to undertake enhanced training on the FCPA and ethics and to submit certifications annually demonstrating the completion of such trainings.

Noteworthy Aspects

- Cooperation by the Batista Brothers. Joesley and Wesley Batista cooperated with the agencies, which helped lessen the fines they faced. The Batista brothers also had agreed to resign from management and Board positions at J&F and JBS. Further, the Batistas agreed to take enhanced FCPA trainings. As part of the agreement, the SEC acknowledged that it did not seek a penalty over $550,000 against the Batista brothers due to their cooperation with the investigation. It is also of interest that in May 2017, Joesley Batista secretly recorded then-Brazilian president Michel Temer endorsing payments to a politician that had been jailed due to political corruption. The recording was then used by Joesley Batista to help secure a plea bargain to avoid corruption investigations. However, Joesley Batista later accidentally provided prosecutors recordings of conversations where he stated he had violated certain terms of the plea bargain. The status of any criminal actions against the Batista brothers in Brazil and the United States is unclear at the moment.

- U.S. Imposition of Penalties and Disgorgement, Following Substantial Penalties in Brazil. In reaching the plea agreement the DOJ adjusted their fines in light of the Brazilian Leniency Agreement entered into by the defendants. Under the agreements in Brazil, as summarized in the plea agreement, J&F agreed to pay a fine of approximately $1.4 billion and to support "social projects" in Brazil through payments of $414 million. As such, the SEC did not seek a fine against JBS and instead only sought disgorgement. Both agencies also emphasized that the conduct covered by each agency's resolution had strong ties to the United States. For the charges raised by the SEC, much of the illicit conduct was related to a U.S.-based publicly listed company, Pilgrims. In turn, the DOJ also acknowledged the Brazilian Leniency Agreement and reduced the criminal fine against J&F in half, but still maintained a substantial fine, likely due to the extent of the criminal conduct that occurred in the United States. For instance, the Batistas used U.S.-based bank accounts as part of the bribery scheme, held meetings in the United States regarding the bribery system, and even purchased and transferred a New York City apartment as a bribe.

- J&F Compliance Remediation. J&F agreed to implement a compliance and ethics program to help prevent FCPA violations and agreed to continue to monitor internal controls and policies to ensure compliance with anticorruption laws. J&F also committed to establishing appropriate policies and procedures to prevent such illicit activity. Further, J&F agreed to certain reporting on the effectiveness of its ethics and compliance program for three years. Under the SEC Order, J&F agreed to establish a compliance committee and to train directors at J&F and its affiliates on anti-corruption. The DOJ declined to impose a compliance monitor for J&F, citing the fact that J&F will have its compliance program "audited annually by an independent party."

Goldman Sachs Settles FCPA Charges for $2.9 Billion, Losing Out on Maximum Cooperation Credit, But Escaping Imposition of a Monitor

As previously reported, on October 22, 2020, Goldman Sachs Group Inc. (together with its subsidiaries and affiliated entities, Goldman), a New York-based, multinational financial institution, agreed to pay criminal authorities and regulators, including in the United States, United Kingdom, Hong Kong, and Singapore, more than $2.9 billion to resolve allegations of FCPA violations in connection with the 1Malaysia Development Bhd. (1MDB) investigation. The resolution included $2.3 billion in penalties and fines and $606 million in disgorgement, although the DOJ and SEC reduced the amount Goldman had to pay. Goldman entered into a Deferred Prosecution Agreement with the DOJ and its Malaysian subsidiary pleaded guilty to conspiracy to violate the FCPA's anti-bribery provisions. The DOJ agreed to credit amounts paid to the SEC and other American and foreign regulators, resulting in a $1.26 billion criminal penalty owed to the DOJ, including $500,000 to be paid by the Malaysian subsidiary. The SEC announced a Cease-and-Desist Order against Goldman charging the company with FCPA anti-bribery, books and records, and internal accounting controls charges. The SEC assessed a $400 million civil money penalty and disgorgement of $606 million. The SEC agreed to credit against the disgorgement a payment previously made by Goldman to Malaysia and 1MDB in August 2020.

The parallel settlements cover conduct dating back to 2009, when 1MDB, an investment and development company wholly owned by the Malaysian government, was formed. According to the Information filed by the DOJ, Goldman and various of its employees conspired to provide more than $1.6 billion to, or for the benefit of, foreign officials and their relatives. The disposition documents state that, as a result of the bribe payments, Goldman was engaged on a number of projects, including to assist 1MDB in connection with three bond offerings in 2012 and 2013. The offerings raised approximately $6.5 billion for 1MDB and, along with a related acquisition and additional transaction, earned Goldman in excess of $600 million in fees and revenue.

According to the SEC's Order, rather than all of the funds from the offerings flowing to 1MDB projects for the economic benefit of Malaysia and its people, $2.7 billion of the money raised was misappropriated, not only going toward bribes and kickbacks to officials in Malaysia and Abu Dhabi, but also to the personal benefit of participants in the scheme, including former Goldman managing director Tim Leissner. As previously reported, in 2018, Leissner pled guilty to conspiracy charges related to his role in the scheme. The disposition documents note that approximately $18.1 million of the bribes were paid from accounts controlled by Leissner. Further, and as previously reported, Malaysian financier Low Taek Jho (Jho Low), who worked as an intermediary in relation to 1MDB and other government officials, also personally benefitted from the scheme, leading to a $700 million civil forfeiture of assets accrued by him and his family in October 2019.

The disposition documents state that each bond transaction required layers of review under Goldman's internal accounting controls, including by internal committees. Nonetheless, the documents assert that these controls were either circumvented or inaptly applied, allowing the involvement of Jho Low, who employees in the company's "control functions knew . . . posed a significant risk." For example, as described in the SEC's Order, the Goldman Sachs Capital Committee issued conditional approvals and identified follow-up steps in connection with the bond deals, but the results of these steps were not adequately documented.

The documents state that Goldman did not voluntarily disclose its conduct and did not receive full cooperation credit because the company "was significantly delayed in producing relevant evidence, including recorded phone calls." Goldman ultimately received partial cooperation credit for its production of evidence located in other countries, updates to regulators, and "making foreign-based employees available for interview in the United States." Moreover, despite the regulators' stated concerns regarding the company's internal controls and certain compliance systems, Goldman avoided the appointment of a monitor and instead is required to annually report to the DOJ for the next three years regarding its remediation and implementation of compliance measures. The company's DPA also contains language requiring Goldman to self-report "any evidence or allegation of conduct that may constitute a violation of the money laundering laws" or the FCPA.

Noteworthy Aspects

- Substantial Effect of Reduced Cooperation Credit for Delayed Production of Telephone Recordings: The Goldman disposition is by far one of the largest FCPA resolution to date (based on amounts actually paid to the SEC and DOJ), measured in penalties and disgorgement. Comparing it against the similarly large resolution with Airbus from early 2020 is insightful. The primary differences between the Goldman disposition and the Airbus resolution involve (1) disgorgement and (2) cooperation. Disgorgement calculations generally are heavily fact-specific, since they are based on calculated profits from transactions affected by the conduct under investigation. Cooperation determinations are also fact-specific but generally are within the control of a company once it is under investigation – that is, the salient facts relate to company actions that occurs after the conduct under investigation. And it is clear that cooperation was a significant factor in the differences in penalty levels between the Airbus and Goldman resolutions. Both companies faced criminal fines with the DOJ between $2.789 billion and $5.579 billion, based on relevant calculations using U.S. Sentencing Guidelines factors. However, Airbus received a 25 percent discount for its cooperation and remediation, the maximum permitted for companies that do not self-disclose under the DOJ's FCPA Corporate Enforcement Policy. Goldman, on the other hand, received only a 10 percent reduction despite providing "all relevant facts known to it." According to the DPA, Goldman did not receive full cooperation and remediation credit because of "significant" production delays, primary related to recorded telephone calls as noted above. Particularly in light of the size of the penalties at issue, the difference in cooperation discounts tangibly demonstrates the impact of the DOJ's assessment of "full cooperation."

- No Monitor Despite the Dispositions' Findings of Significant Controls and Compliance Program Failings: Goldman avoided an independent compliance monitor despite findings noted in the disposition documents of significant shortcomings in the company's compliance program and related internal accounting controls. Instead, Goldman agreed to implement heightened controls and additional policies and procedures related to electronic surveillance and investigation, due diligence on proposed transactions and clients, and the use of third-party intermediaries, and self-report on the status of those improvements to the DOJ. Goldman's parallel settlement with the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System also required Goldman to submit to the Federal Reserve within 90 days written plans to enhance Goldman's existing anti-bribery compliance program, including upgrades to transactional due diligence and corporate governance and management oversight. In addition, the Federal Reserve settlement required firm management, using personnel who are independent of the relevant business lines and acceptable to the Federal Reserve, to conduct a review at the appropriate time to validate that Goldman's revised anti-bribery compliance program complies with applicable U.S. laws and meets certain specified requirements. At the end of the process, the independent review personnel must submit a report of their findings to the Federal Reserve.

The DOJ's Information states that in addition to certain Goldman employees and agents circumventing controls, "other Goldman employees and agents who were responsible for implementing its internal accounting controls failed to do so in connection with the 1MDB bond deals." Specifically, according to the Information and as addressed above, "although employees serving as part of Goldman's control functions knew that any transaction involving Low posed a significant risk, and although they were on notice that he was involved in the transactions, they did not take reasonable steps to ensure that Low was not involved." For example, the due diligence process raised significant red flags, including Low's involvement, that were either ignored or "only nominally addressed so that the transactions would be approved and Goldman could continue to do business with 1MDB." The DOJ noted that "the only step taken by the control functions to investigate that suspicion [that Low was involved] was to ask members of the deal team whether Low was involved and to accept their denials without reasonable confirmation." At a conference shortly after the settlement, the head of the SEC's FCPA unit, Charles Cain, also called out Goldman's compliance program for failing to work at the most important time. "Even in the least robust programs, it will work with the least consequential transactions," Cain said according to media reports. "But it really needs to work when you have the most pressure to get a deal done by the most senior people involved."

The DPA noted that Goldman "ultimately engaged in remedial measures" including "enhanced" due diligence on third parties, training for management, and "implementing heightened controls and additional procedures and policies relating to electronic surveillance and investigation." The DOJ noted that, based on these measures and the self-reporting commitments regarding compliance program and controls improvements, an independent compliance monitor was "unnecessary." It is likely that a combination of Goldman's progress on compliance and controls remediation (as defined under the FCPA Corporate Enforcement Policy) combined with effective advocacy and the current DOJ policy inclination against imposing monitors (as indicated in the 2018 Benczkowski Memorandum and trends in recent dispositions) to reach this result. - Continued Coordination Among U.S. and International Enforcement Agencies: As is becoming increasingly common, Goldman's settlement went beyond resolving investigations with the DOJ and SEC. Goldman concurrently agreed to dispositions with the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System ($154 million penalty), the New York State Department of Financial Services ($150 million penalty), the U.K. Financial Conduct Authority and Prudential Regulation Authority ($126 million penalty split evenly between them), the Attorney-General's Chambers of the Republic of Singapore ($122 million), the Monetary Authority of Singapore, the Commercial Affairs Department of the Singapore Police Force, and the Hong Kong Securities and Futures Commission ($350 million). The DOJ agreed to credit $100 million of the penalty that Goldman paid to the Hong Kong Securities and Futures Commission, and the entire penalty paid to the other agencies, both international and domestic.

- DOJ Adds New Attachment E – Disclosure Certification Form: Paragraph 21 of the DPA requires Goldman's CEO and CFO to certify, at the conclusion of the deferred prosecution period, that Goldman has met its Paragraph 6 obligations to disclose "any evidence or allegation of conduct that may constitute a violation of the money laundering laws that involve the employees or agents of the Company, or should the Company learn of any evidence or allegation of conduct that may constitute a violation of the FCPA's antibribery or accounting provisions had the conduct occurred within the jurisdiction of the United States." Although the DOJ has required similar certifications in the past, the Goldman DPA includes a new required form certification at Attachment E (which was also used with J&F in that disposition announced the week before). In addition to reciting the Company's disclosure obligation as defined by Paragraph 6, the certification goes on to specify that the obligation "extends to any and all Disclosable Information that has been identified through the Company's compliance and controls program, whistleblower channel, internal audit reports, due diligence procedures, investigation process, or other processes." The certification form also emphasizes the importance of Paragraph 6 to the satisfaction of the company's obligations under the DPA and concludes by referencing the sections of the U.S. criminal code that apply to the form, including as to false statements to the U.S. government for purposes of 18 U.S.C. § 1001. The DPAs announced since Goldman's settlement, Beam Suntory Inc. and Vitol Inc., include a similar form certification at Attachment E.

U.S. Beverage Company Beam Suntory Inc. Resolves Investigation by DOJ into India Bribery Scheme for Over $19.5 Million

On October 22, 2020, the Chicago-based beverage company Beam Suntory Inc. (Beam) entered into a DPA with the DOJ Criminal Division's Fraud Section and the U.S. Attorney's Office of the Northern District of Illinois (USAO) to resolve an investigation under the FCPA. One of the largest producers of distilled beverages worldwide, Beam agreed to pay a criminal monetary penalty of $19,572,885 to resolve a charge of one count of conspiracy to violate the anti-bribery, internal controls, and books and records provisions of the FCPA, as detailed in a Criminal Information issued in the case.

According to the DPA, Beam engaged in a bribery scheme to pay a certain Indian government official to approve its bottling license for distilled beverage products that Beam sought to introduce into the India market. Related to that scheme, Beam also committed internal accounting controls and books and records violations. The disposition documents also note the role played by Beam's U.S. legal department in failing to follow up on evidence of improper activities and practices of Beam India's third-party contractors that presented corruption risks.

As we reported in our FCPA Autumn Review 2018, in July 2018, Beam settled with the SEC for allegations relating to the same conduct, paying over $8 million to the SEC, but the DOJ did not extend any credit to Beam for its earlier payment to the SEC.

Corporate Structure and History

Incorporated in Delaware and headquartered near Chicago, Beam was owned by Fortune Brands Inc., a holding company listed on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), making Beam a "domestic concern" and "U.S. person" within the meaning of the FCPA, until October 2011 when Beam was listed on the NYSE itself. As a publicly traded company, Beam was an "issuer" within the meaning of the FCPA from October 2011 to April 2014, and then it was taken private, again becoming a "domestic concern" under the FCPA, as a subsidiary of Suntory Beverage & Food Ltd, which is traded on the Tokyo Stock Exchange and is itself a subsidiary of the Japanese company Suntory Holdings.

In 2006, Beam acquired a company in India (Beam India), which was a wholly owned subsidiary of Beam throughout the relevant time period whose financial statements were consolidated into Beam's own. According to the DPA, when Beam acquired Beam India as a subsidiary in 2006, Beam did not conduct thorough due diligence on the company and did not replace the company's existing management, which had made improper payments to Indian officials in the past and then continued with such payments until 2012.

India Bribery Scheme

According to the disposition documents, from 2006 to 2012, Beam India used third parties such as sales promoters and distributors to make improper payments to various Indian government officials in order to obtain or retain business in the Indian market, such as securing "orders of Beam products at government-controlled depots and retail stores," "prominent placement of Beam products in government retail stores," "label registrations and licenses," and "distribution of Beam spirit products from Beam India's facility to warehouses in other states in India." Senior members of Beam India's management directed and gave authorization for the improper payments.

The DPA states that Beam India funded the improper payments made by third parties by paying fictitious or inflated invoices submitted by the third parties. Beam India's management kept a second set of financial records to track the amounts and uses of the funds distributed to third parties and disguised the improper payments in the company's books and records as legitimate business expenses such as "customer support," "off-trade promotions," "commissions to distributor/promotor," and "commercial discount ongoing." Regional managers of Beam overseeing the India operations also had knowledge of at least one significant improper payment. The DPA also notes that Beam India management submitted false certifications to Beam that resulted in issues tied to Beam's Sarbanes-Oxley certifications process.

According to the DPA, in 2011, Beam India initiated a rollout of certain Beam beverage products in India. In mid-2011, Beam India contracted a third-party bottling company, which then filed applications with the state Excise Ministry on Beam India's behalf for label registrations to operate the facility and bottle the products in that state. A senior government official of the ministry, who had discretionary authority to deny the application, solicited a bribe of one million rupees (approximately $18,000 at the time) to approve the label registration for Beam India. Senior management of Beam India and regional Beam managers instructed the business to have the third-party bottler make the payment and then conceal it for reimbursement using false invoices for "consulting services." The DPA also summarizes other types of smaller payments to various officials related to the business goals noted above.

Inadequate Internal Controls and Compliance Program Issues

According to the DPA, despite multiple red flags indicating that Beam India might be making improper payments, including serious deficiencies identified by internal and third-party audits, Beam failed to "implement and maintain an adequate system of internal accounting controls" in India. In particular, a global accounting firm hired to review Beam India's compliance efforts and controls reported several concerns in the beginning of 2011, including the lack of many anti-corruption policies and anticorruption training, management's belief that Beam India would not be liable for third parties' conduct, management's assertion that business in India was "very difficult" without making "grease/facilitation payments," employees' belief that "promoters are likely making grease payments" to government officials, Beam India's use of vendors who posed significant corruption risk, and the company's failure to "perform monitoring relative to corruption risks." The firm made several recommendations which Beam did not follow until later in the fall of 2012.

In addition, the disposition documents state that an Indian law firm also advised Beam in early 2011 concerning compliance with Indian laws and regulations. However, Beam regional executives raised concerns that the law firm's review could find indications of improper payments by third parties that, if stopped, could disrupt Beam India's business. The disposition documents state that, in response, the member of Beam's corporate legal department who was managing the Indian law firm's work asserted in an email that, "Beam Legal believes it is critical to approach a compliance review with the understanding that a U.S. regulatory regime should not be imposed on our Indian business and that acknowledges India customs and ways of doing business." Nevertheless, the Indian law firm's report repeated several of the accounting firm's recommendations, such as for FCPA training for employees (particularly on liability arising from third party conduct), due diligence for high-risk vendors, policies and accounting controls for gifts, petty cash, and reimbursement claims, and for third party contracts to include anti-corruption clauses and audit rights.

The DPA notes that a U.S. law firm confirmed and added to the Indian law firm's advice in late 2011. Yet Beam did not follow the recommendations, as the same legal department employee expressed concern to management internally that doing so likely would find information that the company could not affect, "specifically… activities and practices by our [third parties] that we cannot remediate or change." Beam only re-engaged on the issue in late 2012 when it received more allegations of corruption at Beam India.

Noteworthy Aspects

- Only Partial Cooperation and Remediation Credit. The DPA states that certain mitigating credits resulted in a 10 percent discount from the applicable fine as reflected in the penalty of over $19.5 million. The DOJ gave Beam credit for providing all known relevant information, including about individuals involved in the conduct. However, Beam received only partial credit for its cooperation. While Beam did give factual presentations to the DOJ, made foreign-based employees available for interviews in the U.S., and produced documents from foreign countries, the DPA stated that the DOJ considered Beam's cooperation to be "inconsistent and sometimes inadequate." For example, the DPA notes that at times Beam took positions that "were not consistent with full cooperation," caused "significant delays in reaching a timely resolution," and refused "to accept responsibility for several years."

Beam also received only partial credit for engaging in remedial measures. Specifically, the disposition documents note that Beam halted operations in India for a period and took some of the actions recommended by the various external advisors, such as enhancing the compliance program and related internal controls – particularly over disbursements and interactions with government officials, mandating in-person compliance training for employees, hiring high-level compliance officers for Beam India, and hiring new management in India. However, the DOJ stated that Beam did not receive full credit for remediation because the company did not take what the DOJ considered to be appropriate disciplinary action on certain individuals involved in the conduct. - No Voluntary Disclosure Credit or Credit for Payment to SEC. Although it apparently made a disclosure of the conduct at issue, Beam did not receive voluntary disclosure credit under the DPA because before Beam's disclosure a former employee had already alerted U.S. and Indian governmental authorities about "illegal cash transactions" involving Beam's distributors in India. The DPA notes that Beam also did not receive credit for its payment of over $8 million to the SEC in 2018 pursuant to cease-and-desist proceedings relating to the same conduct, because Beam "did not seek to coordinate a parallel resolution" with the DOJ.

- No Compliance Monitor Despite Discussion of Serious Compliance Program and Compliance Management Issues. Despite the variety of issues discussed in the DPA related to Beam's handling of compliance "red flags" and actions taken by members of the company's legal team, the DOJ did not impose a requirement for an independent compliance monitor. The DOJ cited Beam's remedial measures and commitment to continued enhancement of its compliance program and internal controls, as well as a formal requirement for company reporting on the continued upgrades to its compliance program pursuant to Attachments C and D to the DPA, as a basis for this decision. Viewed in conjunction with the DOJ's similar decision in the Goldman Sachs disposition, this result is further evidence of the now-past administration's strong disinclination regarding the imposition of monitors generally, even in cases exhibiting significant compliance program and controls breakdowns and management failures.

Vitol: First Ever DOJ-CFTC Coordinated Resolution

As we discussed in our FCPA Autumn Review 2020, the DOJ charged a former employee of Vitol Inc. (Vitol) in a scheme to make improper payments to government officials in Ecuador, and media reports indicated that Vitol itself was under investigation. Vitol is part of the Vitol Group, which is "one of the largest oil distributors and energy commodity traders in the world," according to the DOJ. On December 3, 2020, the DOJ and Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) announced that they had reached a coordinated resolution with Vitol (which was effectively co-signed by Vitol's parent, Vitol S.A. of Switzerland, from 2004 to 2009), in which Vitol would pay between $90-135 million (depending on any resolutions in Brazil) to the DOJ to resolve criminal charges, and $28.8 million to the CFTC in disgorgements and penalties.

As set out in the DOJ's DPA with Vitol, the DOJ alleges Vitol conspired to violate two FCPA provisions: 15 U.S.C. § 78dd-2 and 78dd-3. Vitol's FCPA violations occurred within two separate arrangements: one of the arrangements focused on Vitol do Brasil's (Vitol Brazil) conduct with Petróleo Brasileiro S.A. (Petrobras) in Brazil from 2005 to 2014, while the other arrangement focused on Vitol's conduct with Empresa Publica de Hidrocarburos del Ecuador (Petroecuador) in Ecuador and Petróleos Mexicanos (PEMEX) in Mexico from 2015 to 2020. The DPA has a three-year term and requires both Vitol and Vitol S.A. to report on the development of their compliance program.

In addition, according to the CFTC's Order, Vitol, without admitting or denying the CFTC's findings, agreed to pay $16 million (down from $83 million, as the DOJ payment and/or any future payment to Brazilian authorities was credited towards the CFTC penalty) as a civil monetary penalty for conduct not covered by the DOJ's DPA, and $12.8 million in disgorgement covering both the profits from foreign corruption and from the alleged Commodity Exchange Act violations.

The DPA and the Order focus on Vitol's bribery activities in Brazil, Ecuador, and Mexico, wherein Vitol would pay officials and corporate insiders for both confidential internal information that benefitted Vitol's trading activities and to gain an improper advantage in obtaining and retaining business in the purchase and sale of oil products. The CFTC's Order also focuses on Vitol's manipulation of the "global physical and derivatives oil markets."

Brazil

As described in the DPA, between 2005 and 2014, Vitol and its individual co-conspirators made a total of $8 million in payments to at least one Brazilian executive official within Petrobras and eight other Petrobras officials in exchange for two forms of confidential Petrobras information. Petrobras officials were given various code names in emails, including "Batman," "Phil Collins," "Golfino," "Beb," "Popeye," and "Tiger," among others. According to the DPA, Vitol earned at least $33 million from its "corruptly obtained contracts with Petrobras."

The DPA describes two separate bribery schemes in Brazil. The first took place between 2005 and 2014 and involved $3 million in payments in exchange for two types of confidential information: "market intelligence" and "last look" information. Market intelligence information included internal Petrobras import and export forecasts, production volume and quality, shipping routes, and cargo loading details. Last look information related to information on confidential competitive bids Petrobras would receive from other companies; Vitol having a "last look" would allow them to match or beat the final bids to allow Vitol to secure Petrobras' business.

Around August 2005, a Vitol trader requested a Vitol Brazil executive find a Petrobras insider who would have market intelligence; the executive was told to focus in the planning/scheduling department. In September 2005, a Petrobras employee agreed to provide the information for bribes ranging from $5,000/month to $12,000/month. These payments went until at least 2014.

Around February of 2006, the same Petrobras employee offered the Vitol Brazil executive last look information, which the executive accepted. Vitol would pay the Petrobras employee 8 cents a barrel for each successful tender. This information was shared with Vitol traders and helped them determine the exact price they would need to bid to win Petrobras tenders – a number Vitol internally referred to as the "gold[en] number." From March 2006 to December 2014, the DPA states Vitol paid for and received last look information for over 50 Petrobras tenders in Brazil, and at least five other occasions for tenders outside of Brazil.

These payments were made through transfers by Vitol S.A. (Vitol's parent company from 2004 to 2009, according to the DPA) to Swiss and U.S. bank accounts held by a "Brazil Sham Company," who would then make payments to a Brazilian "doleiro;" a doleiro is a professional money launderer and black-market money exchanger. These payments were made to accounts in locations including the Bahamas and the Grand Cayman. The doleiros then converted the money into Brazilian Real to pay cash to the Vitol Brazil executive, who would then share the bribe payments with the relevant Petrobras officials.

The second bribery scheme involved payments of more than $5 million to five officials at Petrobras in exchange for confidential pricing information that Vitol used to bid or offer on fuel oil contracts from Petrobras. Vitol engaged consultants who secretly negotiated with one of the Petrobras officials to determine the bribes for the officials and the "commissions" for the consultants, and then held sham negotiations to legitimize these dealings.

In this situation, the Petrobras official solicited a company to pay bribes. Specifically, according to the DPA, in 2011, one of the Petrobras officials sought out a Brazilian consultant to find an oil company who would pay bribes for fuel contracts with Petrobras through Petrobras's trading operation in Houston. The consultant then suggested Vitol, who agreed to pay the bribes in exchange for confidential product and pricing information to allow Vitol to "determine its interest in pursuing a deal for that particular Petrobras cargo shipment."

Vitol, using its own Brazilian consultant, negotiated with the Petrobras consultant on a "final price" which would be different than the actual sale price. The difference in value between the price Vitol actually paid and what Vitol should have paid went to bribes for the Petrobras officials and "commissions" for the Brazilian consultants. Vitol engaged in more than 30 transactions with Petrobras in this matter.