FCPA Autumn Review 2012

International Alert

Introduction

As this quarterly Review went to press, the FCPA bar and company compliance personnel were scrambling to determine when the U.S. enforcement agencies would release the long-awaited FCPA Guidance. Anonymous statements reported in the press had suggested that the agencies were planning to release the Guidance by October 10, 2012, when the OECD Working Group on Bribery gathered in Paris for its annual consultation with the private sector and civil society. The OECD Working Group had in part prompted the agencies to promise the Guidance when, in an October 2010 report, it urged the agencies to "clarify" FCPA requirements and "increase . . . transparency and consistency" of the agencies' primary enforcement methods. (See OECD Phase III Report on the U.S. Implementation of OECD Anti-Bribery Convention, October 21, 2010.) However, that day came and went with no word from the agencies. The next possible release date for the Guidance is October 21, 2012, when the United States is scheduled to provide a written update to the OECD Working Group's October 2010 report. If the release does not occur by then, it likely will occur only after the U.S. election.

While the FCPA bar was planning for the Guidance release, on October 9, 2012, the Serious Fraud Office ("SFO") in the United Kingdom quietly released updated guidance for the U.K. Bribery Act. The primary theme of the update is an expressed re-emphasis on the SFO's role as investigator and prosecutor, rather than provider of corporate guidance, with the result being less detailed commentary on the SFO's views of specific compliance issues. The update revised prior statements regarding: self-reporting of violations and resulting treatment in enforcement actions, "business expenditures" related to hospitality, the treatment of facilitation payments, and the scope of "adequate procedures" for company programs to prevent and detect corruption. Miller & Chevalier will provide detailed analysis of this updated guidance in our next quarterly Review. In addition to updating the Bribery Act guidance, the SFO also enhanced the transparency of its enforcement methods when, earlier this quarter, it publicly released – for the first time – its settlement documents related to a foreign-corruption prosecution, against Oxford Publishing Ltd. (discussed below).

Below, we examine cases and trends from this last quarter. Continuing on the theme of agency transparency (or lack thereof), we will look at two standing areas of concern to the FCPA bar – declinations and "foreign official" definition – that the Department of Justice ("DOJ") and the Securities Exchanges Commission ("SEC") have recently addressed. Before diving into detailed case reports, we will also examine the continued slowing pace of enforcement and the continuing focus on the healthcare industry.

Declinations

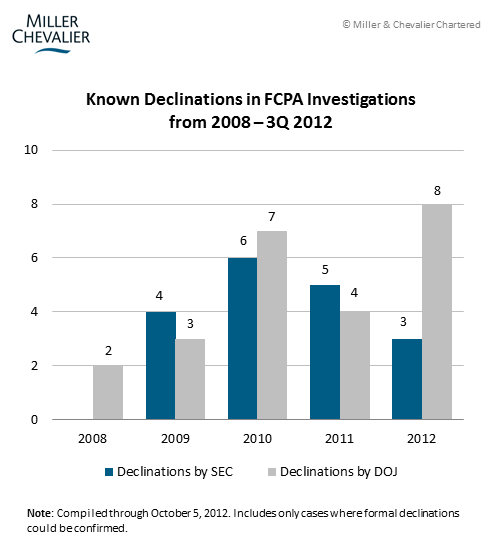

We have noted previously that FCPA declinations – decisions by the agencies to not prosecute a company after initiating an FCPA investigation – are almost never publicized or explained by the authorities. (See Declinations During the FCPA Boom, August 2011.) By scouring SEC filings and other public reports, Miller & Chevalier has tracked the number of known declinations over the past several years.

In terms of raw numbers, we have seen a striking increase in the number of known declinations by the DOJ in 2012, as shown in the chart below. We also note that the SEC data, thus far, does not follow the DOJ's upward trend. Available data does not allow us to determine whether the increase is due to an actual increase in the number of DOJ declinations, or other factors, such as an increase in the public disclosure of declinations. It is possible that the data reflect a response by the DOJ to public and Capitol Hill pressure for more details regarding declinations.

The agencies also appear to be changing their historical practice of neither acknowledging nor explaining their declination decisions. In April of this year, the DOJ and the SEC both publicly announced that they had declined to prosecute Morgan Stanley for misconduct in China traced to a single employee, Garth Peterson, and both articulated several reasons for their decisions in disposition documents (see our detailed coverage in FCPA Summer Review 2012). Since then, based on press reports and SEC filings, we know that the agencies have offered specific reasoning in at least three other declinations, and in one of the three cases, have publicly announced the declination. This table summarizes the four cases:

|

Company |

Reasons given for declination |

Agency announcement? |

| Morgan Stanley | "considering...Morgan Stanley constructed and maintained a system of internal controls, which provided reasonable assurances that its employees were not bribing government officials, the [DOJ] declined to bring any enforcement action against Morgan Stanley related to Peterson's conduct. The company voluntarily disclosed this matter and has cooperated throughout the department's investigation." "Mr. Peterson...actively sought to evade Morgan Stanley's internal controls in an effort to enrich himself and a Chinese government official." |

Yes (April 25, 2012) |

| Hercules Offshore Inc. | "The DOJ...terminated its investigation...'based on a number of factors, including...the thorough investigation undertaken by Hercules and the steps that Hercules has taken in the past and continues to take to enhance its compliance program, including efforts to ensure compliance with the FCPA.'" | No (reported in 8-K dated August 7, 2012) |

| Pfizer Inc. | "In 18 months following its acquisition of Wyeth, Pfizer Inc., in consultation with the department, conducted a due diligence and investigative review of the Wyeth business operations and integrated Pfizer Inc.'s internal control system into the former Wyeth business entities. The department considered these extensive efforts and the SEC resolution in its determination not to pursue a criminal resolution for the pre-acquisition improper conduct of Wyeth subsidiaries." | Yes (August 7, 2012) |

| Academi LLC | "Based upon the [Justice] Department's investigation...we [DOJ] have closed our inquiry..." "We have taken this step based on a number of factors, including...the investigation undertaken by Academi and the steps taken by the company to enhance its anticorruption compliance program." | No (reported in the Wall Street Journal on August 15, 2012, quoting DOJ letter to Academi) |

The declination for Pfizer comes with a caveat: as discussed below, the DOJ and the SEC declined to charge Pfizer, based on a pure successor liability theory, for actions of employees of Wyeth before its acquisition by Pfizer. However, as noted in the DOJ statement, the SEC charged and settled with Wyeth (now a Pfizer subsidiary) directly for the past conduct.

Given the small number of known cases so far, apart from having robust compliance programs and controls, very little can be surmised as to the detailed standards companies must meet to secure a declination. Whatever can be gleamed from the scant reasoning offered in these cases has no precedential weight, and thus offers little predictive value for companies. For those interested in the interplay of factors that drive a declination decision, these cases will not quench a desire for definitive standards that some hope will be found in the long-awaited FCPA Guidance.

"Foreign Official" Definition

A longstanding debate in FCPA compliance circles concerns the scope of the Act's "foreign official" definition – specifically, whether the definition reaches employees of entities owned by foreign governments whose activities are more commercial than governmental in nature. While several district courts have addressed this question in specific factual contexts, the first appeals court, the Eleventh Circuit, is now looking into the question in the Haiti Teleco appeal. During this quarter, the DOJ laid out its arguments in its appellee's brief, which the appellants challenged in their replies. Our detailed coverage of the sparring is below.

Pace of Enforcement & the Healthcare Industry Sweep

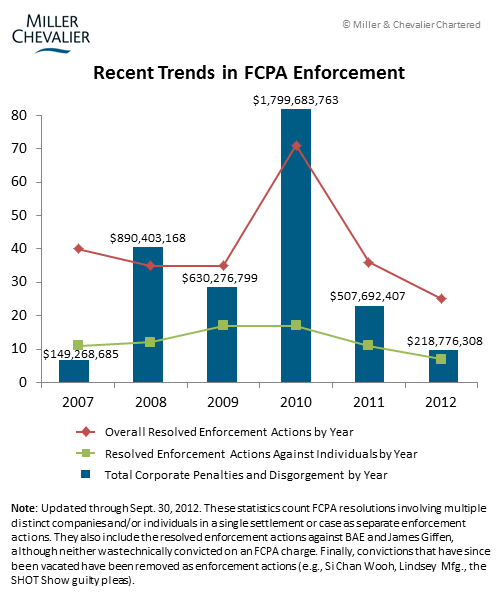

The often reported trend of the apparent slowing pace of FCPA enforcement continues in the third quarter. The chart below shows that since the high of 2010, there has been:

- A continual drop in the number of resolved actions;

- A correspondingly dramatic drop in the total amount of fines imposed; and

- A similar decline in the number of resolved individual prosecutions.

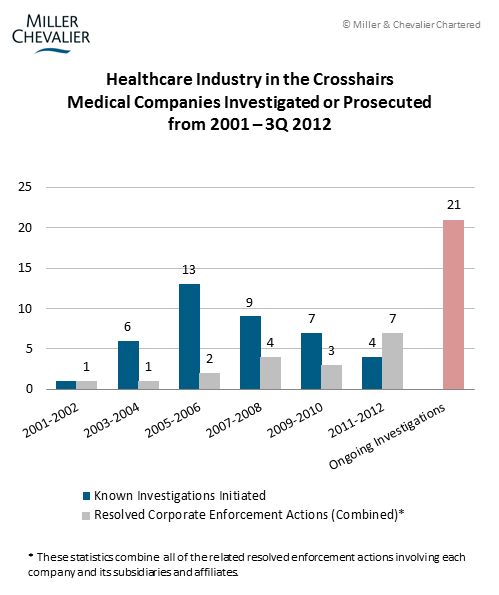

However, to a company in the healthcare industry, hearing about the declining number of FCPA prosecutions may be exasperating, as 11 enforcement actions have been brought so far in 2012 against six companies in the healthcare sector. These cases account for more than 60% of the 18 total corporate dispositions this year to date. Indeed, the numerous cases appear to show that the agencies are developing a standard set of compliance obligations unique to healthcare companies, which we discuss below in relation to Pfizer. New prosecutions from this quarter include: Orthofix, Pfizer, Wyeth, and Tyco. Overall, as the chart below suggests, the almost ten-year old healthcare industry sweep may be entering a phase where the agencies are resolving more cases than they are starting them – this year, at the current rate, the number of resolutions will outnumber new investigations, reversing the growth trend in prior years. But with ongoing investigations against at least 21 companies – some of which have been ongoing for five to eight years – the sweep will likely continue to play out for at least the next few years.

There are other industry sweeps reportedly ongoing, such as the financial services and movie studio sweeps. One industry that is back in the spotlight is defense. It received particular attention from Transparency International UK ("TI-UK"), which, on October 4, 2012, released a corruption ranking of global defense companies, and declared that "[t]wo thirds of defence companies do not provide adequate levels of transparency." The TI-UK study does not assess actual corruption, only compliance and anti-corruption indicators and program elements found on each company's website. This is not the first time the defense industry has come under the spotlight – most recently with the SHOT Show trials, before then, with actions involving companies such as Lockheed and BAE. (See FCPA Summer Review 2012; FCPA Spring Review 2010.)

Also Notable

- FCPA related shareholder derivative litigation: We have reported previously on the rise of private suits linked to FCPA investigations and settlements. Below, we take stock of major resolutions of shareholder derivative suits in the past six months, characterized by their general lack of success.

In addition, as we went to press, Alcoa Inc. announced that it settled its civil suit with Alba, an aluminum smelter owned by the Bahrain government, agreeing to pay $85 million to Alba in two installments. The suit, filed by Alba in 2008, alleged that Alcoa paid bribes to Alba employees and caused Alba to enter into unfavorable contracts. The suit led to a DOJ investigation of Alcoa for FCPA violations. (See FCPA Summer Review 2010 and FCPA Spring Review 2008.) We will provide more detailed analysis in our next quarterly Review.

- International prosecution: Every quarter brings more evidence that countries other than the United State are accelerating their prosecutions of foreign corruption; this time, we discuss prosecutions and settlements in the United Kingdom, France, and Greece.

Actions Against Corporations

Orthofix Settles FCPA Violations by Its Mexican Subsidiary

On July 10, 2012, Orthofix International N.V. ("Orthofix"), a Dutch medical device manufacturer with offices in Texas and shares traded on U.S. exchanges, resolved FCPA charges brought by the DOJ and SEC based on allegations involving its wholly-owned Mexican subsidiary, Promeca S.A. de C.V. ("Promeca").

According to the DOJ Information and SEC Complaint, from 2003 until 2010, Promeca paid routine bribes, which its employees referred to colloquially as "chocolates," to Mexican officials at the state-owned health care and social services agency Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social ("IMSS") in order to obtain sales contracts for orthopedic products with government hospitals. While Promeca also supplied private hospitals in Mexico, approximately 60% of the company's revenues came from sales to IMSS.

The "chocolates," which the pleadings state totaled approximately $317,000, allegedly were transferred in the form of cash, laptop computers, televisions, appliances, and vacation packages. Promeca provided such benefits either directly to Mexican government officials or indirectly to front companies owned by the officials. Over the course of the seven-year period, the bribery scheme reportedly generated approximately $8.7 million in total sales for Promeca, resulting in approximately $4.9 million in illegal profits.

According to the pleadings, from 2003 to 2007, the bribe amounts ranged from 5% to 10% of the value of sales by Promeca to the hospitals in question and were paid to local hospital employees — primarily purchasing directors. In order to fund these illicit payments, Promeca executives allegedly took cash advances which they would account for by submitting falsified invoices for imaginary expenses (e.g., meals, tires). As the size of the bribes increased, the Promeca executives allegedly began to account for them instead as promotional and training expenses.

Beginning in 2008, IMSS instituted a new national tender system under which a special IMSS committee, rather than individual hospitals, selected the companies that would supply IMSS nationally. To ensure that it was awarded business under this new system, Promeca allegedly began making payments to front companies that Promeca employees knew were controlled by certain IMSS officials for purported training and other promotional services in connection with courses, meeting and congresses — services which Promeca never in fact received. These payments reportedly totaled 5% of the value of sales conducted as a result of Promeca's successful national tender in 2008, and 3% of the value of such sales in 2009.

In 2010, according to the pleadings, Orthofix, upon learning of the payments through a Promeca executive, immediately self-reported the matter to the agencies, conducted an internal investigation, and implemented significant remedial measures.

In settling these allegations, Orthofix entered into a three-year deferred prosecution agreement ("DPA") with the DOJ to resolve a criminal charge for failure to maintain sufficient internal controls, and consented to an entry of judgment against it on civil charges brought by the SEC for failure to maintain sufficient internal controls and keep adequate books and records. As a part of these dispositions, Orthofix agreed to pay a $2.22 million criminal penalty, disgorge over $5.22 million in ill-gotten gains and pre-judgment interest (a total of nearly $7.5 million), maintain a corporate compliance program with rigorous internal controls (as outlined in Attachment C of the DPA), and provide periodic reports to the agencies over a two-year period regarding its remediation efforts and the maintenance of its compliance program.

Noteworthy Aspects:

- "Lax Oversight" by Orthofix – Kara Novaco Brockmeyer, Chief of the SEC's FCPA Unit, attributed the occurrence of bribery at Promeca directly to Orthofix's "lax oversight" which she said "allowed its subsidiary to illicitly spend more than $300,000 to sweeten the deals with Mexican officials." The pleadings highlight the company's failure to maintain an adequate system of internal controls, characterizing Orthofix's FCPA compliance policy and training program as inadequate in relation to the extent of the company's international operations, including its ownership of subsidiaries like Promeca that engaged in substantial sales to state-owned enterprises. Beyond the failure to prevent the underlying bribery, some key lapses flagged by the pleadings include:

- Lack of Pre-Acquisition Due Diligence: The Orthofix settlement provides another example of the risks involved in failing to undertake adequate due diligence during the mergers and acquisitions process. Specifically, the DPA states that although Orthofix "grew its direct distribution footprint in part by purchasing existing companies, often in high-risk markets, [the company] failed to engage in any serious form of corruption-related diligence before it purchased Promeca."

- Inadequate Response to Red Flags: When Promeca's training and promotional expenses significantly exceeded budget as a result of the bribery scheme, Orthofix did little to investigate or reduce the excessive spending. For instance, in 2003, Orthofix wrote off approximately $100,000 in cash advances taken out against a Promeca executive's corporate credit card after Promeca could not produce sufficient receipts for the purport travel-related expenditures. Despite monthly reporting requirements and expenditures in high-risk categories that frequently "far exceeded the budgeted amounts in several categories, including promotional expenses, travel expenses, and meetings for doctors," these categories of payments "received no extra scrutiny [from Orthofix] and were in fact budgeted funds from which Promeca made bribe payments over a multi-year period." Orthofix failed to revise its policies to rein in such abuses, including the excessive and unsupported cash advances, until 2010.

- Corporate Audit Inadequacies: Although relevant Orthofix finance personnel discussed the payment of "chocolates" in Mexico's medical device market both with Promeca and amongst themselves, concerns regarding such payments were not elevated to Orthofix's compliance personnel, nor were such concerns reflected in Orthofix's audits of Promeca, which consisted of only the standard statutory audits required under Mexican law and did not contain an anti-corruption review.

- Insufficient Training: The pleadings fault Orthofix for significant training-related shortcomings, including the company's failure to: (a) translate the company's anti-corruption policy into Spanish despite the fact that most Promeca employees spoke minimal English; and (b) provide any FCPA-training to many of its personnel for years, including to Promeca personnel and a key U.S.-based executive with responsibility over developing sales in Latin America.

- Lack of Pre-Acquisition Due Diligence: The Orthofix settlement provides another example of the risks involved in failing to undertake adequate due diligence during the mergers and acquisitions process. Specifically, the DPA states that although Orthofix "grew its direct distribution footprint in part by purchasing existing companies, often in high-risk markets, [the company] failed to engage in any serious form of corruption-related diligence before it purchased Promeca."

- Accounting Charges Only – According to the DPA, Promeca's "financial results were consolidated with Orthofix N.V.'s corporate financial statements, books, and records. Orthofix N.V. was responsible for ensuring Promeca's continued solvency, and Orthofix N.V. periodically infused Promeca with additional capital. Orthofix N.V. and Orthofix Inc. personnel based in the United States oversaw Promeca's activities, reviewed and approved Promeca's annual budgets, and had the authority to hire and fire." Thus, based on the pleadings, the basis for the accounting charges is clear. Neither agency, however, charged Orthofix with an anti-bribery violation, even though the public allegations appear to provide a basis for such charges, considering prior enforcement theories applied by the agencies. Among the Orthofix personnel responsible for Promeca was "Executive A," a Peruvian citizen and U.S. permanent resident based out of Texas, who was responsible for Orthofix's sales operations in Latin America from approximately 1991 to 2008. According to the pleadings, Executive A "knew of the payments and things of value outlined above, but failed to stop the scheme or to report the scheme to [Orthofix's] compliance department."

Nordam Group Enters NPA for FCPA Violations in China

On July 17, 2012, Nordam Group Inc. ("Nordam") – a Tulsa, Oklahoma-based provider of aircraft maintenance, repair, and overhaul ("MRO") services – entered into a three-year non-prosecution agreement ("NPA") with the DOJ to resolve an unspecified number of FCPA-related charges in connection with the company's business in China.

According to the NPA, between 1998 and 2008, Nordam's wholly-owned subsidiary, Nordam Singapore Pte Ltd. ("Nordam Singapore"), and Nordam's affiliate, World Aviation Associates Pte Ltd. (Singapore) ("World Aviation"), made illicit payments of approximately $1.5 million to employees of unidentified state-owned and controlled entities in the People's Republic of China ("China" or "PRC"), including airlines controlled and exclusively owned by the PRC government. The NPA alleges that the Nordam entities intended that the payments would induce the award and retention of contracts to perform MRO services. Several Nordam employees based in the United States allegedly knew about and approved the bribes.

According to the DOJ, Nordam Singapore and World Aviation made and concealed illicit payments to PRC officials in several ways. Initially, the payments – referred to as "commissions" or "facilitator fees" – were made in cash or wired to bank accounts belonging to customer employees, using funds transferred to and then drawn from World Aviation employees' bank accounts. Subsequently, as of about 2002, three World Aviation employees began making and concealing the payments through sales representative agreements entered into with fictitious entities. In some other instances, Nordam, Nordam Singapore, and World Aviation inflated the value of their invoices to customers, thus causing customers to reimburse Nordam for bribes paid to the customers' employees.

Nordam agreed to pay a criminal penalty of $2 million, which, according to the NPA, is "substantially below" the range required by the Sentencing Guidelines. The DOJ praised the company's cooperation and remedial efforts, citing Nordam's "timely, voluntary, and complete disclosure" and "real-time cooperation," including working with "an independent accounting expert" retained by the DOJ "to review the Company's financial condition." In addition, the DOJ noted that Nordam has "fully demonstrated" that a fine exceeding $2 million will "substantially jeopardize the Company's continued viability."

In addition to the fine, Nordam also agreed to report to the DOJ on its compliance efforts on at least an annual basis for a period of three years, and to continue to enhance its compliance program to ensure that the program contains all of the elements specified by the DOJ in the NPA's "Corporate Compliance Program" attachment.

Noteworthy Aspects:

- Aircraft Services Companies in Focus – The Nordam settlement marks the second DOJ settlement this year with a Tulsa-based provider of aircraft MRO services in connection with illicit payments made to foreign officials. The first one was discussed in our FCPA Spring Review 2012, namely, the March 2012 settlement with the DOJ of Tulsa-based BizJet International Sales and Support, Inc., and its indirect parent, Lufthansa Technik AG, in connection with illicit payments to Mexican and Panamanian government officials to influence the award of MRO contracts.

- Economic Hardship Matters to the DOJ – The DOJ's sensitivity to its fine's impact on Nordam's continued viability suggests that, where a proposed fine could result in significant reduction in operations at a defendant company, the company should demonstrate that effect to enforcement officials when negotiating for a lower penalty. As discussed in our FCPA Spring Review 2010, enforcement officials were also responsive to such concerns in settling FCPA-related charges against the chemical company Innospec Inc. ("Innospec"). The DOJ and SEC assessed criminal and civil penalties against Innospec in excess of $160 million but, following an investigation into Innospec's ability to pay, enforcement officials substantially wrote-down the combined penalties to the two agencies to just over $25 million. In addition, a portion of Innospec's criminal penalties were payable contingently, based on continuing income from the company's sales.

Pfizer and Two Subsidiaries' Eight-Year FCPA Investigation Concludes in Settlements

On August 7, 2012, New York-based pharmaceutical, animal health & consumer products company Pfizer Inc. and its subsidiary Wyeth LLC resolved two separate complaints by the SEC alleging violations of the FCPA's books and records and internal controls provisions. On the same day, another Pfizer Inc. subsidiary, New York-based Pfizer H.C.P., entered into a DPA with the DOJ to resolve charges of FCPA anti-bribery violation and conspiracy to violate the anti-bribery and books and records provisions of the FCPA. The settlements, which were previewed in Pfizer Inc.'s third quarter 2011 SEC filing, put an end to an investigation that lasted eight years and extended to 14 countries.

The SEC's Complaints against Pfizer Inc. and Wyeth alleged that employees of Pfizer Inc.'s subsidiaries and their representative offices made payments to government-employed doctors and officials in multiple countries to unduly influence decisions on purchasing, product registration, government reimbursement, and customs clearance. The improper payments and actions took place in a variety of contexts in the following ten countries: Russia, Bulgaria, Croatia, Kazakhstan, Czech Republic, Serbia, China, Pakistan, Indonesia and Saudi Arabia. Pfizer Inc. and Wyeth were connected to the alleged misconduct through actions of their foreign subsidiaries. While the relevant disposition documents state that neither parent companies' employees were aware of the misconduct by their overseas subsidiaries, the subsidiaries' inaccurate books and records were consolidated into the parents' financial statements.

In contrast to Pfizer Inc. and Wyeth, Pfizer H.C.P. was involved in the illegal conduct through employees of its representative offices in Bulgaria, Croatia and Kazakhstan, and through distributors and employees of a representative office of its corporate parent in Russia (Pfizer Russia) (public documents do not state whether the corporate parent was Pfizer, Inc. itself or a subsidiary). The DOJ considered this involvement through representative offices sufficiently direct to extend jurisdiction over Pfizer H.C.P. The DPA states that Pfizer H.C.P. made $2 million in corrupt payments between 1997 and 2006, generating $7 million in illicit profits. Some of the charged misconduct included payments by Pharmacia Corporation, which Pfizer H.C.P. acquired in 2003.

Collectively, the three Pfizer entities agreed to pay $60 million in fines, disgorged profits, and pre-judgment interest. To settle the SEC's charges, Pfizer Inc. and Wyeth agreed to pay $26.3 million and $18.8 million, respectively, in disgorged profits and interest. On the DOJ side, Pfizer H.C.P., entered into a two-year DPA and agreed to pay a $15 million criminal penalty. Pfizer, Inc. also agreed to implement an extensive compliance program and to self-report on the program's implementation and progress to the DOJ and SEC for two years.

Noteworthy Aspects:

- A Tale of Two Acquisitions – The pleadings suggest that Pfizer appropriately conducted acquisition due diligence on Wyeth, and reported results to the agencies within 180 days after closing. Pfizer also integrated the new subsidiary into its compliance program. Although there was no full declination, the SEC did not include any of Wyeth's misconduct in its Complaint against Pfizer, and the DOJ did not bring an action against Wyeth at all. In its press release, the DOJ specifically attributed that decision to Pfizer's diligence and integration, and to the SEC resolution with Wyeth.

Pfizer's acquisition of Pharmacia can be contrasted to that of Wyeth. Pfizer bought Pharmacia in 2003. The pleadings do not discuss any due diligence or integration efforts by Pfizer with respect to that acquisition. However, alleged payments by Pharmacia clearly continued past closing. Payments by Pharmacia were a part of both Pfizer H.C.P.'s and Pfizer Inc.'s resolutions.

These patterns yet again highlight the DOJ's policy of encouraging pre-acquisition due diligence. A commitment to conduct anti-corruption due diligence and prompt integration of new acquisitions are included as a part of Pfizer's enhanced due diligence obligations in Attachment C to the Pfizer H.C.P. DPA.

- Instructive Settlement Documents – The wide range of misconduct described in the settlement documents provides a useful guide of potential red flags – especially for healthcare companies that operate in countries with high corruption risk. In summary, the described conduct includes:

- Conference sponsorship, travel, cash payments, and other benefits as incentives for purchases, and inaccurate recording of these payments in company books;

- Contracts with officials or with companies controlled by officials in exchange for regulatory assistance;

- Payments to health care providers for confidential information;

- Payments to resolve problems with registration and customs clearance;

- Disguising payments to individual doctors as hospital incentives;

- Use of fraudulent vendor invoices to generate cash for improper payments; and

- Payment of sales discounts into distributors' offshore accounts and inaccurate recording of these payments in company books.

- Expanded Compliance Program with Standards Unique to Healthcare Companies, Self-Monitored Implementation – Pfizer, Inc. agreed to continue to implement a comprehensive program of compliance improvements. Attachment C to the DPA describes the elements of the compliance program, including those that Pfizer already enacted and those it agreed to adopt, and requires Pfizer to self-report to the DOJ for two years on the status of its implementation. Specifically, Attachment C.1 outlines the standard corporate compliance program elements; Attachment C.2 describes various enhanced compliance program elements, which largely parallel those included in Attachment D of the Johnson & Johnson DPA (See FCPA Spring Review 2011); and Attachment C.3 sets forth compliance reporting obligations. As in Johnson & Johnson, these enhanced compliance obligations go beyond those the DOJ typically include in the standard corporate compliance program proscribed in settlements, and includes elements particularly applicable to healthcare companies. For example, Pfizer, Inc. has implemented and is required to maintain a Global Policy on Interactions with Healthcare Professionals, complete with corresponding standard operating procedures. These enhanced obligations may evolve into a set of compliance standards uniquely applicable to the healthcare industry.

Oracle Settles SEC Charges Involving "Parked Funds"

On August 16, 2012, the SEC charged California-based enterprise management firm Oracle Corporation ("Oracle") with violations of the books and records and internal controls provisions of the FCPA based on activities of certain employees of its Indian subsidiary, Oracle India Private Limited ("Oracle India"), between 2005 and 2007.

The SEC alleged that in the course of sales to Indian government end-users through local distributors, Oracle India secretly directed excess funds to be "parked" outside of Oracle's books. These excess funds consisted of the difference between what the distributor charged government end-users and took as their fees, and what Oracle India collected from the distributors. The SEC further alleged that one distributor was instructed by certain Oracle India employees to make payments out of the parked funds to third parties on 14 occasions – in relation to eight different government contracts – purportedly for "marketing and development expenses." However, some of the third party recipients of the parked funds were allegedly not on Oracle's approved vendor list and some were mere "storefronts" that did not even exist. The SEC's Complaint did not describe how the funds sent to third parties were subsequently used.

Between 2005 and 2007, approximately $2.2 million in funds were allegedly improperly "parked" with Oracle India's distributors in violation of Oracle's internal corporate policies. The SEC charged that Oracle lacked the proper internal controls to prevent its employees from creating and misusing the parked funds, and the Complaint highlighted the risk that the parked funds could be used for illicit purposes such as bribery or embezzlement.

Oracle discovered the conduct following escalation of a local tax inquiry by Oracle's Asia division. It launched an internal investigation and subsequently voluntarily disclosed the conduct to the SEC. Oracle also took remedial measures to address risks and control issues related to the parked funds, including terminating certain employees, implementing additional due diligence measures, terminating distributors involved in the activities, prohibiting other distributors from creating parked funds, requiring additional representations and warranties from distributors prohibiting parked funds, and enhancing anti-corruption training for its partners and employees.

Without admitting or denying the charges in the Complaint, Oracle agreed to pay $2 million to settle SEC's charges.

Noteworthy Aspects:

- Importance of Monitoring Risks by Distributors – In its Complaint, the SEC faulted Oracle for allegedly knowing that its distributor relationships in India created a margin of excess cash, yet failing to conduct an audit comparing the distributors' margins against the end-user prices to ensure that excess margins were not being built into the pricing structures until 2009. In past actions, such as Biomet and Smith & Nephew, discussed in our FCPA Spring Review 2012, the SEC and the DOJ have also held companies responsible for failing to adequately control known risks posed by distributors. This suggests that the SEC and DOJ expect companies to employ stringent safeguards for distributors as they do for other high-risk third parties, such as sales agents.

- Agency Evaluation of Controls Can Affect Outcome – Like the Morgan Stanley case discussed in our FCPA Summer Review 2012, improper conduct at Oracle's foreign subsidiary (1) was not known to Oracle, (2) could be traced to specific individual actors, and (3) violated Oracle's existing policies. But this case did not result in a declination for Oracle. A likely explanation for this different treatment was the fact that the SEC found fault with Oracle's controls, while the agencies praised Morgan Stanley's program. Thus, even if employees violate a company's policies, the company can still be held to account if those policies and internal controls are deemed insufficient. This case shows, for example, that improper conduct by foreign subsidiary employees remains a compliance risk area requiring significant and ongoing attention, even for parent companies with compliance policies in place.

Tyco FCPA Settlements, Round Two

On September 24, 2012, the DOJ and the SEC each announced that Tyco International Ltd. ("Tyco"), a Swiss manufacturer of security, fire protection, and energy products, had agreed to pay more than $26 million in total penalties to the agencies to resolve allegations that it violated the FCPA's accounting provisions in more than a dozen countries. In a related criminal prosecution, a Tyco subsidiary in the Middle East, Tyco Valves & Controls Middle East Inc. ("TVC ME") pleaded guilty to conspiring to violate the FCPA's anti-bribery provisions relating to payments it made to officials of an oil and gas company controlled by the government of Saudi Arabia.

This action follows a settlement between Tyco and the SEC in April 2006. Then, the SEC charged Tyco with alleged accounting fraud and FCPA anti-bribery violations. (See SEC Settles FCPA Enforcement Action with TYCO, April 20, 2006.) In that settlement, in addition to paying a $50 million penalty, Tyco agreed to be permanently enjoined from violating the FCPA, among other securities laws, and committed to review its FCPA compliance measures and conduct a comprehensive internal investigation of possible additional FCPA violations. The current SEC Complaint explains that the violations underlying this enforcement action were identified as a result of the internal investigation Tyco conducted pursuant to the 2006 settlement.

DOJ Enforcement Actions

According to the NPA, from 1999 to 2009, certain Tyco subsidiaries falsified books, records, and accounts in connection with transactions involving government officials in China, India, Thailand, Laos, Indonesia, Bosnia, Croatia, Serbia, Slovenia, Slovakia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Libya, Syria, the United Arab Emirates, Mauritania, Congo, Niger, Madagascar, and Turkey. These Tyco subsidiaries made improper payments to government officials, both directly and indirectly, and fraudulently recorded those payments as consulting fees, commissions, unanticipated costs of equipment, technical consultation and marketing expenses, conveyance expenses, cost of goods sold, promotional expenses, or sales development expenses. Tyco in turn incorporated the fabricated entries into its own books, in violation of the FCPA's books and records provision.

The Criminal Information against Tyco subsidiary TVC ME alleges that between 2003 and 2006, TVC ME made improper cash payments to officials of Saudi Aramco ("Aramco"), a state-owed oil and gas company in Saudi Arabia. The payments were intended to: remove TVC ME interests from various Aramco "blacklists," win specific project bids, and obtain specific product approvals. TVC ME's "Local Sponsors" – third parties through whom TVC ME paid the bribes – provided TVC ME with false documentation of the payments, including fictitious invoices for consultancy costs, bills for fictitious commissions, or bills for "unanticipated costs for equipment." The Information stated that TVC ME then improperly recorded its bribe payments by using this false documentation.

TVC ME pleaded guilty to one count of conspiring to violate the FCPA's anti-bribery provisions, and agreed to pay a $2.1 million penalty and work with Tyco to fulfill its compliance obligations. Tyco entered into a three year NPA with the DOJ in which it agreed to pay an approximately $13.68 million penalty (which includes the $2.1 million fine against TVC ME). In addition to the fine, Tyco agreed to strengthen its compliance, bookkeeping and internal controls standards and procedures as required by the DOJ's "Corporate Compliance Program" attached to the NPA. The NPA also requires Tyco to report, at least annually, over a three year period, to the DOJ on the implementation of its strengthened compliance programs and ongoing remediation efforts.

SEC Enforcement Action

The SEC's civil Complaint alleges facts substantially similar to those in the DOJ's NPA. With respect to the books and records and internal controls violations, in addition to those countries listed in the NPA, the SEC alleged improper conduct by Tyco subsidiaries in Malaysia, Egypt, and Poland. Overall, the SEC alleged that Tyco subsidiaries in Asia and the Middle East operated at least twelve different illicit payment schemes, starting prior to 2006 and continuing until 2009. As a part of these schemes, the SEC alleges that these Tyco subsidiaries knowingly disguised illegal payments to government officials as commissions and falsely recorded those payments in their books. Tyco then incorporated these inaccurate entries into its financial statements.

According to the SEC, in one of these illicit payment schemes, Tyco also violated the FCPA's anti-bribery provision, through actions of TE M/A-Com, Inc. ("M/A-Com"), a Tyco Turkish subsidiary. In 2006, a New York City-based sales agent of M/A-Com made illegal payments to an instrumentality of the Turkish government in connection with the sale of microwave equipment. Employees of M/A-Com knew of these illegal payments but did not prevent or report them. In its allegations against M/A-Com, the SEC cited an internal email, which stated, "Hell, everyone knows you have to bribe somebody to do business in Turkey. Nevertheless, I'll play it dumb if [M/A-Com's agent] should call." There was no indication that any Tyco officers knew of these payments.

The SEC's press release reported that Tyco entered into a proposed Final Judgment with the SEC in which it agreed to pay approximately $10.5 million in disgorgement and approximately $2.6 million in prejudgment interest. In addition, Tyco agreed to be again permanently enjoined from violating the FCPA.

Noteworthy Aspects:

- Relatively Low Fine and No Monitorship Despite Apparent Violation of Prior Injunction – Many of the alleged FCPA violations in this enforcement action occurred between 2006 and 2009, in apparent violation of the 2006 permanent injunction. Even so, the agencies offered Tyco a comparably low penalty and an NPA, and did not impose a corporate monitor. Tyco's cooperation played a role – the agencies praised Tyco's "extensive efforts to identify and remediate its wrongdoing" and explicitly considered these efforts in crafting the settlement. Another factor may be that the conduct underlying this prosecution was uncovered in the course of Tyco fulfilling its 2006 settlement obligation to conduct a comprehensive FCPA internal investigation. Still, companies hoping to avoid a government-imposed monitor could point to the absence of a monitor in this case to argue that the threshold for requiring a monitorship has risen.

- Need for Comprehensive Training that Reaches High Risk Jurisdictions – In the Tyco NPA, the DOJ specifically emphasized the need for corporate FCPA training programs that reach high-risk countries. The DOJ pointed out that, despite having previously admitted to failing to provide adequate anti-corruption training to its employees in certain high risk jurisdictions (in the 2006 prosecution), Tyco nonetheless allowed weak internal controls and improper conducts to persist in high risk jurisdictions until 2009. To improve internal controls, the NPA requires Tyco to maintain an effective system for providing guidance to employees on compliance issues "in any foreign jurisdiction in which the Company operates."

- Enforcement Actions During Restructuring – The Tyco NPA provides some interesting insights into how the DOJ deals with a company that is restructuring during the period covered by a settlement. The NPA acknowledges that Tyco is in the process of separating into three companies and spinning off its flow control business. The NPA provides that if the spinoff takes place during the period of the agreement, any entity or business unit implicated in the wrongdoing will continue to be bound by the obligations of the NPA (except reporting), and Tyco must specifically include continuing obligation provisions in any spinoff agreements. However, once the spinoff is complete, Tyco would no longer be responsible for ensuring the spun-off entity's compliance with the NPA.

- Continuing Themes in Enforcement Actions – Several Tyco subsidiaries named in the settlement documents operated in the healthcare industry, adding to the long list of healthcare companies under FCPA scrutiny, as discussed in the introduction. In addition, a Tyco subsidiary allegedly made improper payments to a Chinese design institute, a type of government intermediary that has appeared repeatedly in cases involving China, making these institutes a bright red flag for international companies and enforcement agencies alike. (See e.g., Watts Water, FCPA Winter Review 2012; ITT Corp., FCPA Spring Review 2009.)

Actions Against Individuals

SHOT Show Informant Sentenced to 18 Months in Prison

On July 31, 2012, U.S. District Judge for the District of Columbia Richard Leon sentenced Richard Bistrong, the principal informant in the DOJ's SHOT Show prosecution, to 18 months in federal prison, followed by three years of supervised release.

As discussed in prior FCPA Reviews, Bistrong, the former Vice-President for International Sales at Armor Holdings Products, LLC ("AHP"), was arrested in 2007 for helping AHP to illegally secure contracts through the payment of bribes. He was charged with conspiracy to violate the FCPA, the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, and the Export Administration Regulations. After his arrest, Bistrong agreed to cooperate with the FBI in an undercover sting operation aimed at the defense and law enforcement industry. Bistrong acted as an informant and participated in hundreds of recorded meetings and phone calls. The information he gathered was central to the DOJ's charges against 22 individuals for FCPA violations, in relation to a supposed $15 million dollar equipment sales contract to the government of Gabon. (See Historic FCPA Sting Operation Nets 22 Individuals, January 20, 2010; FCPA Autumn Review 2011.) However, after two consecutive mistrials and multiple acquittals and dismissals, the DOJ dismissed all charges against all 22 defendants earlier this year. (See FCPA Summer Review 2012.)

Bistrong pleaded guilty on September 16, 2010, and according to his plea agreement, he faced a maximum of five years in prison, a fine of up to $250,000, and up to three years supervised release. (See FCPA Autumn Review 2010.) DOJ prosecutors urged Judge Leon to sentence Bistrong to probation, arguing that his extensive assistance to the SHOT Show cases warranted leniency, despite the seriousness of the charges against him. However, Judge Leon disagreed that a sentence of only probation would send an appropriate message, and instead noted that prison was the best deterrent against corruption.

Former Morgan Stanley Executive Sentenced to Nine Months for Evading Internal Controls

On August 16, 2012, the former Managing Director of Morgan Stanley's real estate business's Shanghai office, Garth Peterson, was sentenced in the Eastern District of New York by Judge Jack B. Weinstein to nine months in prison and three years of supervised release after pleading guilty to conspiracy to evade Morgan Stanley's internal controls. Peterson had faced a maximum penalty of five years in prison and a maximum criminal fine of $250,000 or twice his gross gain from the offense. Judge Weinstein added a two-point enhancement to Peterson's offense level for abusing a position of trust in a manner that significantly facilitated the commission of the offense, but ultimately reduced the penalty due, in part, to Peterson's acceptance of responsibility and the anticipated deterrent effect of the sentence. As discussed in our FCPA Summer Review 2012, Peterson was alleged to have secretly acquired millions of dollars' worth of real estate investments for both himself and others, including the then-Chairman of a Chinese state-owned entity.

In a related civil case, the SEC charged Peterson with violations of the anti-bribery, and books and records and internal controls provisions of the FCPA, as well as with aiding and abetting violations of the anti-fraud provisions of the Investment Advisors Act of 1940. Peterson consented to a SEC settlement requiring him to disgorge over $250,000 as well as a portion of his ill-gotten real estate interests, valued at approximately $3.4 million. Peterson also agreed to permanent debarment from the securities industry.

Both the DOJ and the SEC declined to bring charges again Morgan Stanley, as detailed in our FCPA Summer Review 2012, due at least in part to the comprehensiveness of the company's internal controls as well as Peterson's deliberate efforts to circumvent them. Because Judge Weinstein determined at sentencing that Peterson had limited assets, Morgan Stanley agreed to waive its right to seek criminal restitution from Peterson.

Ongoing Developments

"Foreign Official" Definition Appeal Now in Hands of Appeals Court

In the "Haiti Teleco" Eleventh Circuit appeal that could, for the first time, allow a circuit court to decide the definition of "foreign official" under the FCPA, the parties have finished their briefings. Following the appellants' opening briefs filed in May (covered in our previous FCPA Review), the DOJ filed its opposition on August 12, 2012, and the appellants, Joel Esquenazi and Carlos Rodriguez, filed their separate replies on October 4, 2012.

We have extensively covered the underlying Terra Telecommunications Corporations ("Terra") case, which involved a scheme by Terra, a U.S. telecom company, to bribe officials of Telecommunications D'Haiti ("Haiti Teleco" or "Teleco"), a state-owned company in Haiti. (See Haiti Teleco discussions, Summer 2012, Winter 2012, Autumn 2011, and Spring 2011.) The alleged scheme involved payments to Haiti Teleco employees in return for rebates, tariff reductions, and other benefits for Terra. For their roles, two Terra executives, Joel Esquenazi and Carlos Rodriguez, were convicted by a jury and respectively sentenced to fifteen-year and seven-year prison terms.

In May 2012, Esquenazi and Rodriguez appealed their convictions. The argument on appeal of most interest to FCPA observers is the appellants' contention that the district court's jury instruction wrongly defined "instrumentality." (See FCPA Summer Review 2012.) The FCPA defines "foreign official" as "any officer or employee of a foreign government or any department, agency, or instrumentality thereof." The statute does not separately define "instrumentality." The district court instructed the jury that "instrumentality" is "a means or agency through which a function of the foreign government is accomplished," and that "state-owned or state-controlled enterprises that provide services to the public may meet this definition." The court also provided the jury the following factors to consider in determining whether Teleco was an instrumentality:

- Whether Teleco provides services to the citizens or inhabitants of Haiti;

- Whether its key officers and directors are government officials or are appointed by government officials;

- The extent of Haiti's ownership of Teleco, including whether the Haitian government owns the majority of Teleco's shares or provides financial support such as subsidies, special tax treatment, loans, or revenue from government-mandated fees;

- Teleco's obligations and privileges under Haitian law, including whether Teleco exercises exclusive or controlling power to administer its designated functions; and

- Whether Teleco is widely perceived and understood to be performing official or governmental functions.

According to the government, the jury was reasonable in finding that Haiti Teleco met this multi-factor test, because the Haitian government "effectively" owned Teleco; the Haitian national bank subsidized Teleco; Teleco's management was appointed by the government; and even Terra's in-house counsel referred to Teleco as an "instrumentality."

On appeal, Esquenazi argued in his opening brief that the term "instrumentality" applies to only "foreign entities performing governmental functions similar to departments or agencies." The DOJ countered that this proposed definition, tying "instrumentality" to a "traditional government function" performed by a "part of the government," is untenable for a number of reasons:

- "Traditional governmental function" should not be a benchmark, since governments around the world differ in what they consider as their functions and in who should carry out those functions;

- The narrow definition effectively reads "instrumentality" out of the statute, since all entities covered by the proposed definitions would fit under other prongs of the "public official" test;

- The narrow definition contradicts Congress's intent to enact broad prohibitions against bribery;

- The narrow interpretation is inconsistent with U.S. obligations under the OECD anti-bribery convention, which includes "public enterprise" in the definition of a public official; the definition of "public enterprise," in turn, includes entities majority-owned by governments regardless of their function. When Congress implemented the Convention, it did not amend the pre-existing "public official" definition in the FCPA, indicating that it intended "instrumentality" to encompass "public enterprise"; and

- District courts that have reviewed this issue largely disagreed with proposed definitions comparable to that advocated by the defendants. For support, the DOJ cited U.S. v. Aguilar; Aluminum Bahrain BSC v. Alcoa, Inc.; and U.S. v. Carson.

In relevant parts, Esquenazi responded that if the government agrees that not all state-owned entities are instrumentalities, then the definition of instrumentality should be independent of government ownership in the enterprise – rather, the definition should depend on the function of the entity. Esquenazi also refers to the definition of "foreign government" in the Dodd-Frank Act – "departments, agencies, instrumentalities, and state-owned entities" – and argues that because Congress intentionally kept the latter two categories separate in Dodd-Frank, it did not mean to combine the categories in the FCPA. Esquenazi also makes use of Opinion Procedure Release 01-12, discussed elsewhere in this Review, in which the DOJ advised that a member of the royal family was not a foreign official. Esquenazi notes that the DOJ came to that conclusion after a thorough examination of the individual's role in the government. He contends that a similar analysis of the entity's governmental function should be applied to Haiti's Teleco, with similar results.

Rodriguez argued in his opening brief that the Eleventh Circuit had already defined "instrumentality" as "part of the foreign government itself," in a case involving the Americans with Disabilities Act, and that this prior definition should apply to the FCPA. The DOJ responded that the Eleventh Circuit precedent interpreting "instrumentality" could not apply because it was not decided in the FCPA context. In response, Rodriguez insists that the use of "instrumentality" is contextually and grammatically similar in the two statutes, therefore, the precedent should apply.

Separately, the DOJ also dismissed Rodriguez's argument that the jury instructions should have required the government to prove that he knew that the bribe recipients were foreign officials – as defined by the FCPA. According to the government, this would effectively require Rodriguez to know that he was violating the FCPA, a requirement that had been refused by other courts. Rodriguez counters that, to violate the FCPA, the relevant legal standard requires that he knew that Haiti Teleco officials possessed characteristics making them "foreign officials" – a legal standard that could be satisfied without him even being aware that the FCPA exists, but which, given the evidence in the case, he did not meet.

The Department also disagreed with appellants' argument that the term "instrumentality" is unconstitutionally vague and suggested that the defendants could have used the DOJ's Opinion Release Procedure to obtain clarifications, but did not. In response, Esquenazi contends that an opinion from the DOJ "on the scope of its current enforcement policy" would not cure the vagueness in statutory language.

Civil Litigation

Recent Settlements and Dismissals in FCPA Related Shareholder Derivative Suits

As noted in this recent article by Miller & Chevalier's James Tillen, shareholder derivative suits are part of an increasing trend of parallel civil litigation following FCPA disclosures. We have periodically reported on settlements and dismissals of these suits, most recently in the FCPA Winter Review 2012. We reported then on the settlement agreement that resolved a consolidated shareholder derivative suit against former directors and officers of SciClone Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Over the past six months, a slew of additional shareholder derivative lawsuits based on FCPA disclosures have been fully or partially resolved, and we review the major resolutions below. The results from this time period signal that these shareholder suits face considerable challenges – in none of these cases did the plaintiff succeed in obtaining damages, and many failed to make it past the motion to dismiss stage.

Settlements

- Halliburton – As reported in our FCPA Winter Review 2009, Halliburton and KBR agreed in February 2009 to a total of $579 million in penalties to settle FCPA charges with the DOJ and SEC related to alleged payments KBR's predecessor company made between 1994 and 2004 in connection with contracts to build and expand a natural gas liquefaction plant on Bonny Island, Nigeria.

In May 2009, two large institutional investors brought derivative claims against the company and certain of its officers and directors in Texas state court alleging that the company's leadership was at fault for the Bonny Island-related misconduct, as well as other unrelated misconduct involving U.S. military contracts, illegal business in Iran, and other assorted wrongdoing. While the institutional investors' suits were consolidated, a Special Advisory Committee of Halliburton's board established a Shareholder Allegation Review Committee ("SARC") to review the allegations. Although the consolidated plaintiffs had alleged that it would be futile to make a demand on the board to investigate the allegations, upon the company's creation of the SARC, they agreed to join the company in seeking a stay of the suit until the SARC finished its investigation. In January 2011, an individual investor submitted a shareholder demand to the board, alleging much of the same misconduct as pled in the consolidated action.

In March 2011, the board received the SARC Report and concluded from the Report that there was no merit to the plaintiffs' claims. Settlement negotiations proceeded from May 2011 until June 4, 2012, when the parties signed a stipulation of settlement. According to press reports, the proposed settlement was finally approved by the court on September 17, 2012.

The end result of the negotiations was similar to that which occurred in the SciClone case. Halliburton agreed to make structural changes to its corporate governance model but did not agree to pay any damages aside from attorney's fees (up to $7 million – as opposed to $2.5 million in SciClone and $3 million in the Maxwell Technologies, Inc.'s shareholder derivative litigation settlement). Some notable governance changes Halliburton agreed to undertake include:

- adoption of a clawback provision that allows the company to reclaim incentive compensation provided to former officers and directors found by a court or the company itself to have engaged in illegal behavior;

- enhanced oversight by the Audit Committee in conjunction with the CEO with respect to compliance functions and risk management;

- establishment of a Management Compliance Committee to evaluate compliance with the FCPA and other significant state and federal laws;

- annual performance reviews for board members and annual consideration of whether CEO and chairman of the board should be the same person;

- annual compliance training for certain employees working in high risk countries;

- greater detail added to the Code of Business Conduct explicitly prohibiting bribery, kickbacks, and the use of unscreened foreign agents;

- expanded intra-company outreach of compliance issues; and, among other things,

- a commitment to identify compliance violations prior to outside discovery.

- Johnson & Johnson – Johnson & Johnson ("J&J") also recently settled an FCPA-related follow-on shareholder derivative lawsuit. As reported in our FCPA Spring Review 2011, in April 2011, J&J resolved FCPA charges with the DOJ and SEC relating to a long-running FCPA investigation into payments allegedly made by the company's subsidiaries to doctors at publicly-owned hospitals in Greece, Poland and Romania, as well as kickbacks the company allegedly paid to the former government of Iraq.

A flurry of shareholder actions in 2010 followed the first reports of the investigation, including both board demand letters and shareholder derivative claims that argued that such demands were futile. J&J's board created a special committee to conduct an internal investigation into the allegations presented by the various shareholder actions, which included both FCPA-related and unrelated products liability and FDA violations claims. The special committee concluded in late June 2011 that direct litigation by the company against its officers and directors was unwarranted. However, the special committee did recommend the establishment of a Regulatory, Compliance and Government Affairs Committee ("RCGC"), which was adopted by the Board.

In response, in August 2011, the shareholders who had submitted demand letters to the board filed wrongful refusal actions. In September 2011, the federal district court in New Jersey overseeing the demand futility actions dismissed those actions without prejudice after rejecting their assertion that a demand on the board would have been futile.

Ultimately, J&J was able to coordinate settlement negotiations with representatives of all of the various shareholder actions, and the federal district court in New Jersey approved the proposed settlement agreement on July 16, 2012. As with Halliburton, the settlement provides for no monetary damages, but requires J&J to implement corporate governance changes and allows for attorney's fees up to $10 million (as well as $450,000 worth of expenses). The core corporate governance changes agreed to by J&J, in addition to those changes made by J&J during the several years since the FCPA investigation was announced, include:

- adoption of a Quality and Compliance Core Objective, adherence to which has been made a factor in the evaluation and compensation of employees;

- adoption of a charter and operating procedure for the RCGC, which is required to meet at least quarterly and to hold separate semi-annual private meeting with J&J's General Counsel, Chief Compliance Officer, Chief Quality Officer, and Vice President of Corporate Internal Audit;

- establishment of a new Product Risk Management Standard.

Dismissals

Not every shareholder derivative action has proceeded as far as the Halliburton, Johnson & Johnson, and SciClone actions did. Notable recent dismissals include:

- Tidewater Marine Int'l, Inc. – As we reported in our FCPA Winter Review 2011, Tidewater Marine International Inc. settled charges with the DOJ and SEC related to a broad FCPA investigation into Panalpina, Inc.'s business practices. Specifically, in July 2010, Tidewater paid over $15 million in fines to the SEC and DOJ combined in connection with the company's activities in Azerbaijan and Nigeria. In February 2011, a shareholder sued Tidewater and certain of its officers and directors in federal district court in the Eastern District of Louisiana based in large part on the information contained in the company's settlements with the DOJ and SEC. But the shareholder never submitted a demand to Tidewater's board to investigate the allegations in the complaint. On July 2, 2012, the court dismissed the case without prejudice after ruling that the plaintiff had not sufficiently alleged that submitting a demand to the board would be futile. On July 23, 2012, the plaintiff filed a motion to stay the proceedings in the case after informing the court that it had decided to submit a demand to the board after all and wanted to await the conclusion of the board's potential investigation.

- Parker Drilling Co. – Another set of shareholder derivative suits stemming from the U.S. government's investigation into Panalpina's business practices met a fate similar to that of the Tidewater actions. Shareholders filed suits in 2010 in state and federal court in Texas against Parker Drilling Company two years after the company first disclosed that it was under investigation by the SEC and DOJ for possible FCPA violations related to its operations in Nigeria and Kazakhstan. Neither the state nor the federal plaintiffs submitted demands to the company's board and both the state and federal courts twice dismissed the suits after concluding that the plaintiffs had failed to adequately plead demand futility. In both state and federal courts the plaintiffs had been allowed to amend their complaints to overcome the deficiencies in their original pleadings, but in neither case were the plaintiffs successful in doing so. The federal case was dismissed on March 14, 2012, and the state case was dismissed on July 23, 2012.

- Smith & Wesson – A similar result occurred in the shareholder derivative lawsuit against Smith & Wesson Holding Corp. related to the failed bribery sting prosecution known as the SHOT Show trials (see FCPA Spring Review 2012) of, among others, Amaro Goncalves, a former vice president of sales at Smith & Wesson. In September 2010, two shareholders filed derivative suits against the company and certain of its officers and directors in Nevada state court. The actions were later consolidated and moved to federal district court in Massachusetts in July 2011. This move coincided with the company's announcement that its own internal bribery investigation had closed. In late July 2012, the federal district court overseeing the matter dismissed the case after ruling that the plaintiffs had failed to make a demand of the board and had failed to show that making such a demand would have been futile.

- Wal-Mart – At least one court in Delaware has made it difficult for plaintiffs to reach the motion to dismiss stage. Only one month after the New York Times's report of possible systematic bribery at Wal-Mart de Mexico, Wal-Mart's Mexican subsidiary, a shareholder derivative suit was filed in Delaware state court. According to press reports, on July 16, 2012, at a hearing to determine who would be appointed lead plaintiff and lead counsel in the case, the court refused to appoint anyone to either position because the two largest institutional shareholder plaintiffs had failed to make a books and records request to inform their claims as is permitted under Delaware law. The court instead told the parties to come back after the only institutional shareholder that had made such a request had obtained access to the company's books and records.

Key Lessons

Although each of the cases discussed above is unique and the resolution of each, in part or in full, has been the result of a mix of calculations made by shareholders, the respective companies' officers and directors, plaintiff's attorneys, and insurance companies, all of whom have their own risk tolerances, some key points may be taken from an examination of these cases:

- Shareholders generally have not been successful in avoiding the demand requirement.

- Board investigations of shareholders' allegations are time-consuming and none of the investigations discussed above concluded that direct litigation was in the company's best interest.

- Among the major recent resolutions, no company, nor any of their officers or directors, has admitted liability, and no damages, aside from attorney's fees, have been obtained.

- Attorney's fees awarded in these cases have ranged from $2.5 million at the low end to up to $10 million at the high end.

- Corporate governance measures instituted as part of the settlement process add to whatever changes in corporate structure had been required by settlements with the DOJ or SEC.

U.S. Agency and Legislative Developments

SEC Announces First Award under Whistleblower Program

On August 21, 2012, the SEC's Office of the Whistleblower announced the first payout from its new program rewarding tipsters who provide evidence of securities fraud, including FCPA violations, to the SEC. Established in August 2011, the program offers financial incentives to whistleblowers who provide original and useful information leading to SEC enforcement actions resulting in more than $1 million in sanctions. Awards can range from ten to 30 percent of the money collected. See our FCPA Reviews from Winter 2012, Summer 2011, and Winter 2011 for more background on the program and its rules.

This first recipient under the program will receive nearly $50,000, representing 30% of the money collected by the SEC in the case. The amount could increase if the SEC collects more money. According to the SEC, the whistleblower provided information that significantly aided its investigation and likely prevented the victimization of many more investors. A second person who also offered information in the case did not receive an award because the information provided did not help the enforcement case.

Few other details about the payout are known – the SEC protects the anonymity of whistleblowers in the program. Whistleblowers are, however, required to disclose their identities to the SEC to receive any award.

The whistleblower program has had its share of critics. Commentators have complained that the incentives undermine internal compliance programs because the rules do not require that the whistleblower first report issues to the company. The SEC responded by creating a rule potentially giving whistleblowers a higher percentage award if they report internally before coming to the SEC. However, critics maintain that the rule is insufficient to encourage individuals to report internally before going to the SEC.

SEC officials have continued to express enthusiasm for the program. In a press release, Chairwoman Mary L. Schapiro remarked, "[t]he whistleblower program is already becoming a success. We're seeing high-quality tips that are saving our investigators substantial time and resources." Sean McKessy, Chief of the Office of the Whistleblower, has reported that the Office receives about eight tips a day. He added, "[t]he fact that we made the first payment after just one year of operation shows that we are open for business and ready to pay people who bring us good, timely information."

DOJ Issues First Opinion Procedure Release of 2012

On September 18, 2012, the DOJ issued its first Opinion Procedure Release of 2012, providing some guidance on the meaning of "foreign official" under the FCPA. In this case, a U.S. lobbying firm ("Requestor") planned to engage a third party ("Consulting Company") to introduce it to the Embassy of a foreign country that the Requestor would like to represent in its lobbying activities. In addition to introducing the Requestor to the Embassy, the Consulting Company would advise the Requestor on cultural issues, act as the Requestor's business sponsor in the foreign country, help the Requestor establish an office there, and identify additional business opportunities for the Requestor there. Because one of the three partners in the Consulting Company was a member of the Royal Family of the foreign country, the Requestor asked the DOJ: "(1) whether the Royal Family Member is a ‘foreign official' under the FCPA; and (2) whether the Requestor's proposed engagement with the Consulting Company would result in any enforcement action by the Department."

Citing a mix of factors drawn from a past Opinion Procedure Release (10-03) and from the court's opinion in United States v. Carson, the DOJ concluded that the Royal Family Member was not a "foreign official" and that the Department would not take action against the proposed engagement under the described facts and circumstances. In its analysis of whether the Royal Family Member was a "foreign official," the DOJ considered: "(i) how much control or influence the individual has over the levers of government power, execution, administration, finances, and the like; (ii) whether a foreign government characterizes an individual or entity as having governmental power; and (iii) whether and under what circumstances an individual (or entity) may act on behalf of, or bind, a government." Here, the release noted that the Royal Family Member did not have any government decision-making power, could not ascend to a government position as a result of his status, did not have any benefits or privileges because of his status, and had no relationship – personal, professional, or familial – with decision-makers in his country with the power to award the business the Requestor was seeking. In coming to its conclusion, the DOJ assumed that the Royal Family Member would not hold himself out as someone acting on behalf of the Royal Family.

While the DOJ did not explicitly rely on these two factors, the agency also noted that (1) the Requestor and the Consulting Company incorporated FCPA-specific safeguards in their proposed business arrangement, and (2) the foreign country's laws do not prohibit the Embassy from engaging the Requestor directly.

International Developments

Oxford Publishing Settles with SFO and World Bank for African Bribery

On July 3, 2012, the SFO announced an enforcement action against Oxford Publishing Limited ("OPL") for alleged unlawful payments made by its wholly-owned Kenyan and Tanzanian subsidiaries, Oxford University Press East Africa ("OUPEA") and Oxford University Press Tanzania ("OUPT"). OPL itself is a wholly-owned subsidiary of London-based Oxford University Press (OUP).

The SFO stated in its press release that between 2007 and 2010, OUPEA and OUPT offered and made corrupt payments intended to induce recipients to award the companies publishing contracts to supply foreign governments with textbooks. In 2011, OUP became aware of possible irregular tendering practices involving OUPEA and OUPT and immediately retained independent counsel and forensic accountants to investigate. OUP voluntarily reported the concerns to the SFO in November 2011, who then instructed OUP to follow guidance set forth in the then-current SFO publication, "Approach of the Serious Fraud Office to Dealing with Overseas Corruption", which instructed companies on the SFO's practices and standards relating to voluntary disclosure and settlement in foreign corruption cases. In addition, because two of the affected contracts were funded by the World Bank, OUP voluntarily reported the matter to the World Bank. According to the SFO, OUP's investigation was "thorough" and "completed to the satisfaction of the SFO," and the investigation result was presented to both the SFO and the World Bank.

The London High Court ordered OPL to pay £1,895,435 ($2,940,621) and reimburse the SFO £12,500 ($20,238) for the cost of pursuing the order. The settlement was agreed to under Part 5 of the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 ("POCA"). As previously explained in our FCPA Spring Review 2012, unlike proceedings under the U.K. Bribery Act, which are criminal and personal in nature (against individuals and corporations), proceedings under the POCA are always civil and only against property.

The SFO gave a few reasons, some of which are outlined below, as to why it pursued civil recovery instead of criminal prosecution. First, the SFO stated that the matter at hand did not meet relevant criteria for criminal prosecution; specifically, key material obtained from the investigation was judged not to be evidentially admissible for criminal prosecution, and witnesses necessary for a prosecution were in overseas jurisdictions and unlikely to cooperate. Second, OUP had conducted itself in a manner that "fully meets" the SFO's applicable conduct criteria, and there was no evidence that the allegations took place with "knowledge or connivance within OUP." Third, the SFO would need considerable resources to investigate the matter further, while a civil recovery would allow the SFO to more strategically deploy resources into other investigations. Fourth, the products ultimately supplied were of a good standard and provided at "open market" value, rather than unsuitable or unnecessary products sold at inflated prices.

The SFO noted that OUP had enhanced its compliance procedures to reduce the risk the conducts in question will recur. Also, as a part of the High Court's Order for Disposal by Consent, OUP agreed to appoint an Independent Monitor to ensure that OUP's "policies, procedures and controls as actually implemented are adequate." Interestingly, the Order requires that the Independent Monitor's review "shall be proportionate and limited to the prospective application of such policies, procedures and controls and shall not include any retrospective review of past events, allegation or other historical circumstances." The Monitor must report to the Director of the SFO within twelve months. There is no required time period that the Monitor must be assigned; rather, the Order intends that the Monitor will be discharged upon the SFO being satisfied that those internal corporate policies meet the required standards.

Noteworthy Aspects:

- Coordinated Settlement with the World Bank: On the same day the SFO announced its consent order with OUP, the World Bank also announced its plans to debar OUPEA and OUPT from future Bank tenders for three years. Notably, the SFO cited the Bank's debarment decision in explaining its decision to pursue only civil recovery. According to the Bank, OUP agreed to pay the Bank $500,000 as a part of the Negotiated Resolution. In addition, the Independent Monitor will also report its review findings to the Bank, in addition to and separate from its report to the SFO.

- Voluntary and Unilateral Donations by OUP: In addition to the payments required by the civil recovery order, OUP unilaterally promised to donate £2,000,000 ($3,238,195) to not-for-profit organizations to support teacher training and other educational purposes in sub-Saharan Africa. The donation is not included in the civil recovery order because, according to the SFO, voluntary payments of this kind are "not [the SFO's] function."

- SFO's Method for Calculating Recovery: The SFO generally described the method it used to calculate the recovery amount. The Office took the price of the affected contracts as revenue derived from unlawful conduct, and deducted certain costs (not including the cost of the bribes paid) from the revenue to arrive at the recoverable benefit obtained by OPL. The SFO did not disclose how it calculated the costs, but stated that its "approach to costs was conservative, with the result that the agreed methodology produced a higher figure than would normally be recognized as trading surplus in the accounts."