FCPA Summer Review 2010

International Alert

Introduction

The second quarter of 2010 ended with a bang with respect to Foreign Corrupt Practices Act ("FCPA") enforcement, and the third quarter is off to an active start, as the U.S. Government imposed $703 million in fines and disgorgement on additional companies in connection with the payment of over $180 million in bribes allegedly paid to Nigerian government officials to build liquefied natural gas facilities on Bonny Island, Nigeria.

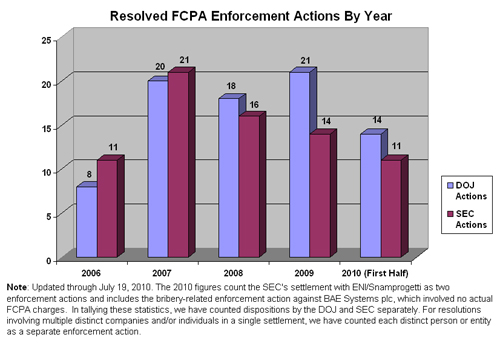

Notwithstanding a leadership transition at the U.S. Department of Justice ("DOJ" or the "Department") and a new FCPA enforcement organization at the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission ("SEC"), there were a total of 11 resolved FCPA-related enforcement actions in the second quarter and the early part of the third quarter -- five involving individuals and six involving corporations. The number of prosecutions of individuals reflected a continuing enforcement focus on individuals, although not at the level of the first quarter spike, which saw 23 individuals indicted by the DOJ on FCPA-related charges in the highly publicized "Shot Show" cases.

The second quarter of 2010 did see a number of significant developments in addition to FCPA enforcement actions. Considerable interest and publicity accompanied the departure from government of Mark Mendelsohn, who, as the DOJ's Deputy Chief of the Criminal Division's Fraud Section, was the country's leading FCPA prosecutor for the past five years. Chuck Duross was appointed in Mendelsohn's place as the Acting Deputy Chief of the Fraud Section. At the SEC, Gerald Hodgkins was appointed Associate Director of the Division of Enforcement, and the Commission opened a new regional unit in its San Francisco office dedicated to FCPA enforcement.

In addition, FCPA enforcement will be affected by proposed amendments to the federal Sentencing Guidelines, new guidance from the Justice Department on the use of independent compliance monitors, and the financial reform bill which establishes rewards for whistleblowers who assist in SEC investigations.

Outside of the United States, the United Kingdom -- much criticized in the past for its failure to implement and enforce the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention -- passed an anti-bribery law, banning both the payment and receipt of bribes. As discussed below, the ensuing publicity suggested far-reaching enforcement authority under the law, although forthcoming guidelines and the actual pattern of enforcement that follows may be more telling. In France, a French court placed French oil company Total S.A. under investigation for corruption, and German prosecutors reportedly initiated an investigation of German engineering company Ferrostaal AG.

Actions Against Corporations

Additional Companies in TSKJ Consortium Settle Charges related to Bonny Island, Nigeria Bribery Scheme

The DOJ and SEC settled charges with additional companies involved in the alleged payments of some $180 million in bribes to Nigerian officials in exchange for contracts valued at over $6 billion for the construction of liquefied natural gas facilities on Bonny Island, Nigeria.

On July 7, 2010, Italian energy company ENI, S.p.A. ("ENI") and its former Dutch subsidiary Snamprogetti Netherlands B.V. ("Snamprogetti") settled charges with the SEC related to the bribery scheme. The SEC charged ENI with violating the FCPA's books and records and internal controls provisions, and Snamprogetti with violating the FCPA's anti-bribery provisions, falsifying books and records, and circumventing internal controls. ENI and Snamprogetti will jointly pay $125 million in disgorgement to settle the SEC charges. The DOJ also filed a criminal information against Snamprogetti, charging the company with one count of conspiracy to violate the FCPA's anti-bribery provisions and one count of aiding and abetting violations of the anti-bribery provisions of the FCPA. Snamprogetti, ENI, and Saipem S.p.A. (which currently owns Snamprogetti) entered into a two-year Deferred Prosecution Agreement ("DPA") with the DOJ, agreeing to pay a $240 million penalty.

On June 28, 2010, Technip S.A., a global engineering, construction and services company based in Paris, settled charges with the DOJ and SEC related to the bribery scheme. Technip entered into a DPA with the DOJ to settle charges of one count of conspiracy and one count of violating the anti-bribery provisions of the FCPA. In its settlement with the SEC, the company consented to the entry of a court order to settle charges of FCPA anti-bribery and accounting violations. Technip agreed to pay a $240 million criminal penalty in its DPA with the DOJ and to disgorge $98 million in profits to the SEC related to the violations.

The charges relate to the alleged participation by Snamprogetti, Technip, Halliburton's former subsidiary Kellogg Brown & Root, Inc. ("KBR"), and the Japanese engineering and construction company JGC Corporation of Japan (collectively, the "Joint Venture"), in a scheme to secure engineering, procurement and construction ("EPC") contracts related to the Bonny Island project with the government-controlled company Nigeria LNG Ltd. ("NLNG"). In particular, between 1995 and 2004, the Joint Venture allegedly engaged Jeffrey Tesler and an unnamed Japanese trading company to pay over $180 million in bribes to a range of Nigerian government officials, including top-level executive branch officials. Joint Venture executives allegedly authorized the hiring of Tesler and the Japanese agent for the purpose of paying bribes. Additionally, senior executives of Technip and Snamprogetti, and other co-conspirators, allegedly accompanied Stanley, KBR's former CEO, to meetings with successive top-level Nigerian executive branch officials to designate representatives with whom the Joint Venture could negotiate bribes and the amount of bribes to be paid.

In charging Snamprogetti, ENI and Technip with internal controls violations, the SEC alleged that the companies conducted inadequate due diligence on Tesler (though he is not named in the SEC's complaint) and the Japanese agent.

JGC Corporation of Japan, the only Joint Venture member that has not settled FCPA charges with the U.S. Government, disclosed in its latest annual report that the company is in talks with the DOJ regarding a potential resolution of FCPA-related charges. The company did not say how much it has reserved, if anything, for a settlement with the DOJ.

The settlements follow the February 2009 settlement in which Halliburton, KBR, Inc., and Kellogg Brown & Root, LLC (which held a 25% interest in the joint venture) paid a total of $579 million in penalties (a $402 million criminal fine and $177 million in disgorgement), that then marked the highest total fine imposed against a U.S. company.

Noteworthy Aspects:

- Guidance on Level of Due Diligence Expected by Enforcement Agencies: Details regarding Technip's inadequate due diligence review of Tesler, as described in the SEC's complaint, provide guidance on the types of inquiries expected by enforcement agencies. Specifically, the SEC notes that the due diligence procedures adopted by Technip "only required that potential agents respond to a written questionnaire, seeking minimal background information about the agent. No additional due diligence was required, such as an interview of the agent, or a background check, or obtaining information beyond that provided by the answers to the questionnaire." Indeed, a senior executive of Technip admitted that the due diligence procedures were a "perfunctory exercise, conducted so that Technip would have some documentation in its files of purported due diligence." Such statements reinforce the current concept of "best practices" that due diligence reviews must be carried out in good faith to uncover potential risks, and should include information from outside sources (i.e., other than from the third party and internal company personnel) and, where appropriate, interviews.

- Corporate Compliance Program: Under the terms of their DPA, Snamprogetti, Saipem and ENI have implemented, and must continue to implement, a compliance and ethics program to prevent and detect not only FCPA violations but also the anti-corruption provisions of Italian law, and other applicable anti-corruption laws throughout their operations. In Attachment C of the DPA, the DOJ lists the elements that, at a minimum, must be included in the corporate compliance program.

- Continuing Prosecutions: Several entities and persons have faced, or are expecting to face enforcement actions related to the Bonny Island corruption scheme. In 2008, Stanley pleaded guilty to conspiracy. In 2009, Halliburton and KBR agreed to a total of $579 million in penalties (all but $20 million of which Halliburton agreed to indemnify) to settle FCPA charges with the DOJ and SEC. The United States is currently seeking the extradition of agents Tesler and Chodan (both U.K. citizens) from the United Kingdom to face FCPA charges. Both have lost their extradition hearings in London. Tesler has said he plans to appeal. Additionally, according to press accounts, M.W. Kellogg Limited ("MWKL"), a 55% KBR-owned U.K.-based joint venture, is expected to settle related charges in the United Kingdom.

- Total Monetary Penalties Related to Bonny Island Scheme Exceed Landmark U.S. Siemens Settlement: Currently, the amount of monetary penalties related to the corruption scheme totals over $1.2 billion, which exceeds the landmark 2008 U.S. settlement with Siemens ($800 million).

- Anti-bribery Charges for Foreign "Issuer": The cases represent another instance where U.S. enforcement agencies have charged foreign issuers with FCPA violations. The DOJ and SEC asserted jurisdiction over Technip as an "issuer" under the FCPA because it had American Depository Shares registered and listed on the New York Stock Exchange for several years during the scheme, and over ENI because it has common stock and American Depository Shares listed on the New York Stock Exchange. The cases demonstrate the expansive reach of the FCPA and U.S. enforcement agencies' continuing willingness to prosecute foreign companies subject to FCPA jurisdiction.

- Substantial Reductions in Fines: Technip's DPA notes that Technip's criminal fine of $240 million is approximately 25% below the bottom of the applicable Sentencing Guidelines fine range of $318.4 million. This may be in recognition of Technip's cooperation with U.S. enforcement agencies, which the DPA describes as "full and truthful." Similarly, according to the DPA for Snamprogetti, Saipem and ENI, their $240 million combined penalty is about 20% below the low point of the fine range of $300 million to $600 million. In the DPA, the DOJ acknowledged Snamprogetti, Saipem and ENI's past and future cooperation with the investigation, and their adoption and maintenance of remedial measures.

- Selective Use of Monitors: Snamprogetti, Saipem and ENI did not have to retain a monitor. The DPA stated that the companies have implemented, and will continue to implement, a corporate compliance program. In comparison, Technip agreed to retain an independent compliance monitor for a two-year period.

On June 29, 2010, Veraz Networks Inc. ("Veraz"), a U.S. telecommunications company, consented to the entry of a court order settling the SEC's charges of FCPA books and records and internal controls violations. According to the consent order, Veraz agreed to pay a $300,000 civil penalty. The SEC settlement comes just over two years after Veraz received a confidential inquiry letter from the SEC relating to alleged FCPA violations and three years after the vendor of telecom data management and transport products went public.

According to the SEC complaint, in 2007 and 2008, Veraz resellers, consultants, and employees made and offered payments to employees of government-controlled telecommunications companies in China and Vietnam for the purpose of improperly influencing those employees (characterized as "government officials" in the SEC complaint) to award or continue to do business with Veraz. The SEC complaint states that Veraz failed to accurately record the payments in the company's books and records and failed to implement a system of effective internal controls to prevent the payments in violation of the FCPA. In total, Veraz employees and third parties paid or offered to pay approximately $40,000 to employees of state-controlled companies in China. In one instance, a Veraz consultant offered a 15% "consultant fee" -- approximately $35,000 -- to an employee of a telecommunications company to secure a $233,000 contract. Veraz discovered the payment offer before receiving any proceeds from the contract and cancelled the deal. In Vietnam, Veraz employees made or offered an unspecified amount of improper payments to employees of state-controlled companies in Vietnam through a Singapore-based reseller. Such payments included payments to the CEO of the Vietnamese government -controlled telecom company and flowers given to the CEO's wife.

Noteworthy Aspects:

- Industry Focus: As a newly-public company that derives the majority of its revenue from non-U.S. sales, Veraz quickly came under SEC enforcement officials' scrutiny. Veraz is the most recent in a growing list of telecom companies investigated and charged by enforcement officials for alleged FCPA-related violations, including UTStarcom, Latin Node, Lucent Technologies, and Haiti Teleco.

Actions Against Individuals

On June 25, 2010, Ousama Naaman, a Lebanese/Canadian dual national and resident of Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, pleaded guilty in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia to charges related to his role in making various improper payments to Iraqi officials on behalf of U.S. chemical producer Innospec Inc. ("Innospec") and its foreign subsidiaries. As reported in our FCPA Autumn Review 2009, Naaman was previously indicted for paying kickbacks to the Saddam Hussein regime on behalf of Innospec in exchange for contracts with the Iraqi Ministry of Oil ("MoO") under the U.N. Oil for Food Program, and for paying bribes to MoO officials after the fall of the Hussein regime. In July 2009, Naaman was arrested in Germany, and later extradited to the United States. As reported in our FCPA Spring Review 2010, in March 2010, Innospec settled enforcement actions brought by U.S. and U.K. authorities relating to the same underlying improper payments in Iraq, as well as improper travel and entertainment expenses for Iraqi officials, improper payments in Indonesia, and violations of U.S. embargo laws. Initially, in May 2010, Naaman pleaded not guilty before reaching the current plea agreement with the DOJ. In the current case, Naaman settled charges of one count of conspiracy to defraud the U.N. and to violate the FCPA's anti-bribery and accounting provisions, and one count of violating the FCPA's anti-bribery provisions.

Under the plea agreement, Naaman must continue to cooperate with the DOJ and foreign authorities in ongoing investigations. Upon sentencing, Naaman may receive up to ten years imprisonment and fines up to $350,000 or twice the gain from the offenses.

Noteworthy Aspects:

- Additional Bribery Schemes: While the allegations contained in the superseding information and statement of the offense in the current case for the most part track those in Naaman's earlier indictment and the prior enforcement action against Innospec, the pleadings in this case contain noteworthy additional information. Specifically, the pleadings indicate that several schemes to bribe MoO officials after the fall of the Hussein regime were never consummated (i.e., no bribes were paid). The pleadings state that although two Innospec executives believed that Naaman would pay $150,000 to MoO officials to ensure that a competing product failed a field test, and Naaman agreed to do so, Naaman in fact did not pay the officials and instead retained the money. The pleadings also note that Naaman and two Innospec executives negotiated to pay over $2.5 million in bribes to MoO officials in exchange for a long term purchase agreement, but goes on to indicate that the bribes were in fact not paid. Such charges based on offers, promises, and authorizations to pay bribes reinforce that FCPA anti-bribery liability does not require the actual payment of a bribe.

- Jurisdictional Questions: The pleadings in the current case raise questions as to the DOJ's jurisdiction over Naaman with respect to the anti-bribery charge. The pleadings state that Naaman's conduct is subject to the extraterritorial jurisdiction of the United States pursuant to 15 U.S.C. § 78dd-1(g). Under Section 78dd-3, the FCPA's anti-bribery prohibitions do not cover foreign individuals unless the violation has a territorial nexus to the United States. However, § 78dd-1(g), titled "Alternative Jurisdiction," extends coverage to "United States Persons" (U.S. nationals and certain organizations) acting outside of the United States, irrespective of whether such persons use the means of interstate commerce. Here, Naaman, a Lebanese/Canadian dual national, would appear not to qualify as a United States Person, which would make § 78dd-1(g) inapplicable. Additionally, because the pleadings note only indirect connections between Naaman's actions and the United States (e.g., notification from a bank branch in New York to Innospec's foreign subsidiary, notification from a foreign inspection company to the United Nations in New York, filing of Innospec's financial statements in Washington DC), it is unclear whether Naaman's actions would satisfy the territorial nexus requirements of 78dd-3. In sum, while jurisdiction clearly existed for the conspiracy charge (the scheme involved a U.S. issuer and at least one U.S. citizen), it is unclear whether the DOJ had jurisdiction to bring the anti-bribery charge against Naaman.

Dimon, Inc. Individuals Settle Charges with the SEC

On April 28, 2010, four former executives of global tobacco merchant Dimon, Inc. ("Dimon," predecessor to Alliance One International, Inc.) settled charges with the SEC relating to improper payments to officials in Kyrgyzstan and Thailand. The four executives, Bobby Elkin Jr., Baxter Myers, Thomas Reynolds, and Tommy Lynn Williams, consented to the entry of final judgments permanently enjoining them from violating the FCPA's anti-bribery provisions and from aiding and abetting FCPA accounting violations. Myers and Reynolds also agreed to pay civil penalties of $40,000 each. Elkin and Williams were not required to pay any fine.

According to the SEC complaint, between 1996 and 2004, Dimon's Kyrgyz subsidiary paid over $3 million in bribes to various Kyrgyz officials to allow the company to purchase tobacco for resale. Specifically, Elkin, Dimon's Country Manager for Kyrgyzstan, allegedly made the bribe payments from a Dimon-funded bank account held under his name (the "Special Account") to three types of officials: (1) employees of JSC GAK Kyrgyztamekisi ("Tamekisi"), a government-established entity that had control over export licenses, (2) local public officials ("Akims"), who could prevent Dimon from purchasing local tobacco by sending police to block entrances of buying stations, among other means, and (3) tax officials, who fined the company and threatened to seize its bank accounts and inventory. As a result of the payments, Dimon was able to purchase local tobacco and obtained a reduction in tax penalties. Myers, Dimon's Regional Financial Director, allegedly knew about the Special Account and authorized multiple fund transfers from a Dimon subsidiary to the Special Account. Reynolds, Dimon's International Controller based in the United Kingdom, also allegedly knew about and was involved in recording payments from the Special Account.

In Thailand, between 2000 and 2003, Dimon allegedly colluded with two of its competitors to pay bribes of approximately $542,590 to officials of the Thailand Tobacco Monopoly ("TTM"), which is owned by the government of Thailand, in exchange for over $9 million in sales contracts with the TTM. Specifically, a portion of Dimon's selling price to the TTM was allegedly designated as "special expenses" or "special commissions," which were in reality amounts to be paid as kickbacks to TTM officials. Dimon allegedly made the kickback payments through an unnamed agent. According to the complaint, Williams, Dimon's Senior Vice President of Sales based in the United States, directed the sales to the TTM and authorized the bribe payments. In particular, Williams instructed Dimon personnel to make payments to the agent, characterized as a "retainer" or "special commissions," in numerous wire transfers over several days or weeks (presumably to avoid detection). The SEC further alleged that Williams knew that Dimon and others had provided a purported business trip to Brazil for TTM officials, which was actually a sightseeing trip to the Amazon jungle and various Brazilian waterfalls, among other places. In addition, Dimon and its competitors allegedly paid for a subsequent sightseeing trip for TTM officials, which involved a one-week stay in Madrid and Rome during the return portion of a trip purportedly to examine tobacco in Brazil.

The complaint charged all four defendants with violating the anti-bribery provisions of the FCPA and with aiding and abetting violations of the FCPA's accounting provisions. The SEC press release noted that the settlement with Elkin took into account his cooperation with the SEC's investigation.

Noteworthy Aspects:

- Levels of knowledge: The varying levels of knowledge of the four defendants illustrate the range of mental states that can result in an SEC anti-bribery enforcement action. At one end of the spectrum, Elkin and Williams allegedly acted with full knowledge of their participation in bribery (e.g., the complaint alleges that Elkins personally delivered bags filled with $100 bills to a high-ranking Tamekisi official at the official's office). At the other end, Myers, Dimon's Regional Financial Director, and Reynolds, Dimon's International Controller, faced anti-bribery charges even though they were not alleged to have actually known about the bribery. Rather, the complaint cites evidence that Meyers and Reynolds should have been aware of warning signs (i.e., red flags) regarding the use of the Special Account. Indeed, the allegations against Myers and Reynolds provide guidance regarding types of access to information and red flags that can be used as evidence of the requisite level of knowledge to sustain an anti-bribery violation. Specifically, Reynolds allegedly (1) received financial information regarding the Special Account, (2) "formalized the methodology" for recording payments from the Special Account, (3) received an internal audit report noting challenges such as a "cash environment," corruption, and a potential control issue with cash, (4) knew that the Special Account was held under the name of an employee, and (5) knew that the Special Account was used to make certain commission payments in cash. The complaint also used language resembling allegations of "willful blindness" or "conscious disregard" of bribery (an alternative means of proving the requisite state of mind to sustain an FCPA anti-bribery violation), noting that Reynolds "did not ask additional questions about the Special Account." Finally, Meyers' level of knowledge appears to have been the lowest of all the defendants. In authorizing fund transfers to the Special Account, Myers allegedly (1) had discussed the Tamekisi and Special Account recordkeeping during a visit to Kyrgyzstan, (2) regularly received documents reflecting activities in the Special Account, and (3) performed certain unspecified accounting functions related to the Special Account.

- Varying levels of penalties: Interestingly, in the settlements, those defendants who acted with apparent actual knowledge of bribery (i.e., Elkin and Williams) received no fines, whereas the defendants who were not alleged to have had actual knowledge of the bribery (i.e., Meyers and Reynolds) received fines of $40,000 each. While Elkin's cooperation may account for his lenient treatment, the rationale behind the relative levels of penalties for the other defendants is not explained in the pleadings. The varying levels of penalties imposed by the SEC may reflect the SEC's new system of evaluating cooperation by individuals. As reported in our FCPA Spring Review 2010, in January 2010, the SEC issued a policy statement describing a new "analytical framework" for evaluating an individual's cooperation in deciding the enforcement penalty against that individual.

- Less than actual knowledge: The enforcement actions in this case represent the second time in one year that the SEC has independently brought anti-bribery charges against individuals based on evidence of less than actual knowledge of bribery. In May 2009, as reported in our FCPA Spring Review 2009, Thomas Wurzel settled anti-bribery charges with the SEC based on allegations that he consciously disregarded a high probability of bribery. As in the current case, the DOJ has not brought a parallel enforcement action against Wurzel despite a lack of obvious jurisdictional impediments. One reason the DOJ might have foregone parallel enforcement actions against the four Dimon executives and Wurzel is that the evidence may have been insufficient to satisfy the stringent "beyond a reasonable doubt" standard required in criminal proceedings. Because SEC enforcement actions are civil proceedings, the SEC need only satisfy the less stringent "preponderance of the evidence" standard. This lower standard may enable the SEC to be more aggressive than the DOJ in pursuing enforcement actions against individuals in the face of limited evidence of knowledge of bribery.

Virginia Man Sentenced to Record Prison Sentence for FCPA-Related Violations

On April 19, 2010, Charles Paul Edward Jumet was sentenced to serve 87 months in prison for his role in a conspiracy to violate the FCPA through improper payments made to Panamanian officials and for making a false statement to federal agents. In addition to his prison term, Mr. Jumet was ordered to pay a $15,000 fine and to serve three years of supervised release. The 87-month prison term is the longest imprisonment ever imposed against an individual for an FCPA-related violation. Mr. Jumet is a former executive of Ports Engineering Consultants Corporation ("PECC"), a company organized under the laws of the Republic of Panama with an office in Richmond, Virginia.

On June 25, 2010, Mr. Jumet's co-conspirator John W. Warwick was sentenced to 37 months in prison for his role in the conspiracy. Additionally, Mr. Warwick was sentenced to serve two years of supervised release following his prison term and ordered to forfeit $331,000 in proceeds of the crime.

As described in our FCPA Winter Review 2010 and FCPA Spring Review 2010, the conspiracy involved unlawful payments of over $200,000 to Panamanian maritime officials and shell corporations owned by the officials or associated with their relatives.

Former Haitian Government Official Sentenced

On June 1, 2010, former Haitian government official Robert Antoine was sentenced to 48 months in prison in connection with his role in a bribery and money laundering conspiracy. Antoine was further ordered to serve three years of supervised release following his prison term, pay $1,852,209 in restitution, and forfeit $1,580,771.

Antoine was the Director of International Relations for Telecommunications D'Haiti ("Haiti Teleco"), Haiti's state-owned national telecommunications company, from May 2001 to April 2003. According to the Indictment, as Director of International Relations for Telecommunications for Haiti Teleco, Antoine was responsible for negotiating contracts with unidentified international telecommunication companies. In exchange for over $800,000 in bribes, Antoine allegedly provided business advantages to the telecom companies, including preferred telecommunications rates, reducing the number of minutes for which payment was owed, and giving credits toward money owed. According to a Factual Agreement that accompanied Antoine's March 2010 plea agreement, after Antoine left Haiti Teleco, he was employed by two U.S. telecom companies that had paid him upwards of $350,000 for business advantages during his tenure as a Haitian government official. Antoine's employment for those companies included helping to manage his replacement at Haiti Teleco, Jean Rene Duperval, and facilitating the laundering of bribe payments from the telecom companies to Duperval.

As reported in our FCPA Spring Review 2010, as an official and alleged recipient of bribes, Antoine is not directly covered under the FCPA. The DOJ's prosecution of Antoine demonstrates its willingness to prosecute foreign officials for corrupt activity under legal theories other than the FCPA. Antoine pled guilty to one count of conspiracy to commit money laundering.

A jury trial for Duperval and three other individuals involved in the conspiracy, Joel Esquenazi, Carlos Rodriguez, and Duperval's sister Marguerite Grandison, is currently scheduled to begin on July 19, 2010 in U.S. District Court in Miami.

Ongoing Investigations

CCI Former Executive Extradited From Germany to United States

On July 2, 2010, Flavio Ricotti, an Italian citizen and former executive of Control Components Inc. ("CCI"), was extradited to the United States from Germany for his alleged role in a scheme to bribe foreign officials to secure contracts for CCI. CCI is a California-based company that designs and manufactures service control valves for use in the nuclear, oil and gas, and power generation industries.

As reported in our FCPA Spring Review 2009, Ricotti and five other former CCI executives were indicted by a Santa Ana, California grand jury on April 8, 2009, on charges of conspiracy to violate the FCPA. The six former executives included four U.S. nationals and two foreign nationals.

CCI pleaded guilty on July 31, 2009, to charges of conspiracy to violate FCPA anti-bribery provisions and the Travel Act, and two substantive FCPA anti-bribery violations. As part of its plea agreement, CCI agreed to pay an $18.2 million fine, implement and maintain a comprehensive anti-bribery compliance program, retain an independent compliance monitor for three years, serve a three year term of probation and continue to cooperate with the DOJ during its investigation.

Alba's Civil Suit against Sojitz Stayed for DOJ Investigation

On May 27, 2010, the DOJ requested a stay in the civil suit brought by Aluminum Bahrain BSC ("Alba") against the Japanese trading company Sojitz Corporation and its U.S. subsidiary, Sojitz Corporation of America (collectively "Sojitz"). The DOJ filed a motion asking the U.S. District Court in Houston to stay the lawsuit pending a resolution of the agency's ongoing investigation of Sojitz for possible criminal wrongdoing, including potential FCPA violations. The DOJ's investigation reportedly arose from information provided by Bahraini authorities, who have conducted their own probe of Sojitz and have filed money laundering charges against two former Alba employees who allegedly received the bribes.

As discussed in our FCPA Winter Review 2010, Alba filed the suit against Sojitz in December 2009 alleging that Sojitz committed violations of the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act ("RICO"), conspiracy to violate RICO, fraud, and conspiracy to defraud. According to Alba's complaint, officials at Nissho Iwai Corp., a predecessor company that formed Sojitz in 2004, paid almost $15 million in kickbacks to two former employees of Alba, which is majority-owned by the Bahraini government. In a scheme running from 1993 to 2006, Sojitz allegedly arranged to buy aluminum from Alba at unauthorized below-market rates and then resold the aluminum at discounted prices on the U.S. market. Meanwhile, the company wired kickback payments via U.S. banks to bank accounts in Liechtenstein, Switzerland and Britain that were beneficially owned by the former Alba employees. Alba is seeking compensatory damages of more than $31 million in addition to punitive damages, costs, and fees.

This is the second time that the DOJ has intervened in a civil lawsuit filed by Alba alleging that a corporation made corrupt payments to Alba employees. In February 2008, Alba sued the aluminum producer Alcoa, Inc. ("Alcoa") along with a senior executive, William Rice, and an agent, Victor Dahdaleh, in connection with an alleged bribery scheme in which Alba paid hundreds of millions of dollars in overcharges to Alcoa over a fifteen year period. Funds were allegedly funneled through overseas accounts controlled by Alcoa's agent, Dahdaleh, who then used the money to bribe Alba's executives in return for supply contracts. The DOJ intervened in the case soon after the lawsuit was filed, requesting a stay while the agency investigated potential FCPA violations by Alcoa and the individuals named in the lawsuit. The stay remains in effect, and the investigation is ongoing. According to press reports in April 2010, U.S. and U.K. prosecutors discovered financial records linking Dahdaleh, a Canadian citizen living in London, with payments made to a former senior executive of Alba. No charges have been announced against Dahdaleh as of this writing.

HP under Investigation for Bribery in Russia

Hewlett-Packard Co. ("HP") is under investigation by German and U.S. authorities for a suspected €8 million ($10.9 million) in bribes paid to Russian officials in exchange for a €35 million contract to supply computer equipment to the office of the Russian prosecutor. According to press reports, the bribery scheme involved three German agents and money being cleared through numerous shell companies.

In December 2009, German authorities arrested three individuals (including one current and two former HP executives) in connection with the probe. In April, 2010, Russian authorities raided HP's offices in Moscow, reportedly following the request by the Dresden prosecutor. After press reports described the investigation, the SEC and the DOJ announced that they are joining the probe.

Brief Appealing Frederick Bourke's Conviction Filed in Second Circuit

On April 1, 2010, Frederic Bourke filed his opening brief in the Second Circuit appealing his conviction for conspiracy to violate the FCPA and for making false statements to the FBI. (For more coverage of Bourke's case, see our FCPA Winter Review 2010, FCPA Autumn Review 2009 and other past issues.) The charges relate to Bourke's involvement in a failed project to privatize a state-owned oil company in Azerbaijan, in which a scheme of corrupt payments was orchestrated by Viktor Kozeny.

The brief presents several arguments for reversing the verdict. Of most relevance to future FCPA enforcement is the much debated "conscious avoidance of knowledge" standard. As we reported, at Bourke's trial the Government attempted to prove the knowledge element of the FCPA by showing that Bourke "consciously avoided" knowing about Kozeny's bribes. Judge Scheindlin permitted an instruction on conscious avoidance, ruling that it was proper to prove knowledge "if, but only if, the person suspects the fact, realized its high probability, but refrained from obtaining the final confirmation because he wanted to be able to deny knowledge." On appeal, Bourke argues that the Government did not present any evidence that Bourke "deliberately avoided knowledge of Kozeny's bribes." The brief claims that the Government's presentation throughout the trial sought to prove that Bourke actually knew about the bribes. In Government's own words, Bourke "did everything he could to learn about the arrangement" and "didn't look the other way." Conscious avoidance, the brief claims, required the Government to show that Bourke "decided not to learn" about bribery. The Government only attempted to use conscious avoidance as a "fall back" theory, which, according to the brief, is impermissible under the circumstances.

Bourke's brief asserts that although the Government lacked evidence to prove deliberate avoidance of knowledge, it did present evidence tending to show that Bourke "failed to exercise adequate due diligence." This evidence at worst showed that Bourke's conduct was negligent or reckless, but not knowing. Given the instruction on conscious avoidance, however, this evidence could have led the jury to "convict for negligence or recklessness." The jury's confusion between negligence and conscious avoidance was apparent in Bourke's case, the brief claims, in light of the jury foreman's statement to the press after the trial: "We thought he knew and definitely could have known. He's an investor. It's his job to know."

The brief also asserts that the trial court erred in permitting the Government to present evidence that another party refused to participate in the scheme after conducting thorough due diligence. Because Bourke was not aware of this potential investor's due diligence, it had no effect on Bourke's state of mind. At the very least, Bourke claims, the court should have allowed him to present evidence of yet another sophisticated investor (Columbia University), who, like Bourke, did decide to invest after conducting due diligence similar to Bourke's.

The government's response brief is due on July 29, 2010.

Civil Litigation

According to press accounts, on May 7, 2010, El Instituto Costarricense de Electricidad ("ICE"), Costa Rica's government-run telecommunications and electricity provider, brought a civil suit in Dade County Circuit Court against Alcatel-Lucent S.A. and others for their alleged involvement in the bribery of Costa Rican officials to obtain contracts with ICE. As reported in our FCPA Spring Review 2010, Alcatel-Lucent recently announced a settlement in principal with the DOJ and SEC regarding charges of FCPA violations in various countries, including Costa Rica. Additionally, as reported in prior reviews, Christian Sapsizian, a former executive of Alcatel CIT (a predecessor company to Alcatel-Lucent) pleaded guilty in 2007 and received a sentence of 30 months imprisonment and monetary penalties for his involvement in the bribery of Costa Rican officials.

According to press accounts, ICE claims in its civil complaint that Alcatel-Lucent and others violated civil racketeering and other Florida laws by participating in the scheme to bribe Costa Rican officials. ICE reportedly claimed that the bribery was directed in part from Miami, Florida. According to media sources, ICE's claims under Florida law could allow it to recover three times the amount of damages it has suffered.

U.S. Legislative/Regulatory Developments

Amendments to the Sentencing Guidelines

On April 29, the U.S. Sentencing Commission submitted to Congress revised amendments to the federal Sentencing Guidelines with important implications for corporate governance. The proposed amendments will become effective on November 1, unless disapproved by Congress. As discussed in our FCPA Spring Review 2010, the Commission announced proposed reforms in January that included significant amendments to Chapter 8 regarding the sentencing of organizations. The Commission solicited public comment and held a public hearing on its proposals before voting on a revised version of the amendments on April 7.

The final amendments retain many of the proposals announced in January albeit with a few key revisions. The amendments preserved the most noteworthy change proposed in January, a three-level mitigation of an organization's culpability score where the organization has implemented direct reporting by the compliance officer to the board of directors. Under the final language of the amendments, an organization is eligible for the sentence reduction for an effective ethics program even where high-level personnel within the organization were involved in the offense if: (1) the compliance officer has direct access to the board of directors; (2) the organization's compliance program detects the criminal activity, and (3) the company quickly self-discloses the criminal activity to the government.

In revised commentary regarding the requirements for an effective compliance and ethics program, the Commission replaced the previously proposed reference to a corporate monitor with a reference to an "outside professional advisor." The change was reportedly made in response to concerns that the language about monitors would create a virtual requirement for a corporate monitor to demonstrate the effectiveness of a compliance program. The Commission rejected proposed language that would have made appointment of a corporate monitor one of the available conditions of probation. The revised amendments also removed the reference to employees' knowledge of the organization's document retention policies as an aspect of an effective compliance program.

SEC Whistleblower Provision in Financial Reform Legislation

On July 15, 2010, the U.S. Senate approved the final version of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, which establishes a significant new program to reward whistleblowers who assist in SEC investigations. The bill is expected to be signed by President Obama. Both chambers of Congress passed their own respective versions of financial reform legislation, and the two bills were reconciled in conference committee in June. As discussed in our FCPA Spring Review 2010, the SEC whistleblower provision could dramatically impact FCPA enforcement and companies' compliance strategies.

Both the House and Senate financial reform bills proposed the new initiative to reward whistleblowers who voluntarily provide original information to the SEC that leads to a successful enforcement action with sanctions of at least $1 million. The whistleblower provision grew out of a proposal by Representative Paul Kanjorski (D-PA), who chaired a series of House Financial Services subcommittee hearings in spring 2009 focusing on the Madoff scandal. In testimony at a hearing in February 2009, Madoff whistleblower Harry Markopolos suggested expanding the existing SEC whistleblower program for insider trading to apply to all types of securities fraud. The SEC Inspector General made similar recommendations in a letter to Rep. Kanjorski on June 30, 2009. After Kanjorski proposed the reward program in October 2009 in a bill to strengthen SEC enforcement, the House Financial Services committee voted to incorporate the provision into the broader financial reform bill.

The final language in Section 922 of the bill largely tracks the language of the Senate proposal, with an award of at least 10%, but not to exceed 30%, of the monetary sanctions collected in SEC enforcement actions and "related actions" brought by other agencies, including the DOJ, federal and state regulatory authorities, and foreign law enforcement agencies. According to the Senate Banking Committee report on the Senate bill, the Senate proposal was modeled after the IRS whistleblower program enacted in 2006, which includes a 15% minimum award. The Banking Committee emphasized the importance of promoting the predictability and enforceability of rewards to incentivize whistleblowers to come forward with information about violations. While the SEC is given discretion over whether a whistleblower receives an award under the proposal, the Committee expressed its intention for the program to be used "actively," with "ample rewards."

Given the incentives for whistleblowers generated by FCPA cases with substantial monetary penalties, the whistleblower program could significantly tilt the balance toward companies making early voluntary disclosures. Companies will find it increasingly difficult to delay a voluntary disclosure if employees could become multi-millionaires by beating the company to the SEC's doorstep. Moreover, companies are well-advised to encourage internal reporting and to address employees' concerns quickly rather than risking an SEC enforcement action based on whistleblower information.

Additionally, Section 1504 of the act directs the SEC to issue rules requiring that any "Resource Extraction Issuer" include in its annual report information relating to any payment made by the issuer, any subsidiary of the issuer or "any entity under the control of the issuer" to the Federal Government or any "foreign government, [ ] department, agency, or instrumentality of a foreign government or a company owned by a foreign government, as determined by the Commission" for the "commercial development of oil, natural gas, or minerals." The Act defines a "Resource Extraction Issuer" as any issuer required to file a report with the SEC that "engages in the commercial development of oil, natural gas, or minerals." The law's language appears to reach only to the Federal and foreign governments and their agencies and instrumentalities (including national oil companies or NOCs), not to payments made to individual government officials. Nonetheless, the extent of the law remains vague, particularly the reach of the definition of "Resource Extraction Issuer" and whether Congress intended the law to reach beyond direct producers and to companies that support resource extraction. It is possible that the SEC rule-making procedures will add some clarity but, in any event, this provision will add an additional layer of disclosure obligations for many companies engaged in natural resource development. Miller & Chevalier will continue to monitor developments in this area and issue further alerts as appropriate.

U.S. Agency Developments

Opinion Procedure Release Addresses Hiring of a Foreign Official

On April 19, 2010, the DOJ responded to a request from a U.S. company (the "Requestor") regarding the proposed hiring of a foreign official pursuant to an agreement between the U.S. government and another country.

The Requestor entered into a contract with a U.S. government agency to design and construct a particular facility in the foreign country. Under the contract, the Requestor is obligated to hire and compensate individuals to work at the facility as directed by the U.S. agency. The foreign country selected an individual as director of the facility, and the U.S. government agency directed the Requestor to hire the individual. The Requester then entered a subcontract with another company to hire and compensate the individuals selected to work at the facility, including the Facility Director.

The release states that the individual hired as Facility Director currently serves as a paid officer for an agency of the foreign country, and thus is considered to be a "foreign official" within the meaning of the FCPA. However, the DOJ indicated that it did not intend to take any enforcement action with respect to the Requestor's proposal. The DOJ emphasized that while the director is a foreign official whose salary will be paid by the Requestor, the official is being hired pursuant to an agreement between the U.S. government and the foreign country, and the Requestor is contractually bound to hire and compensate the official as directed by the U.S. government agency. In addition, the foreign country appointed the Facility Director based upon the individual's qualifications for the position; the Requestor played no role in selecting the individual. Moreover, the official's position in the foreign government does not relate to the work at issue, and the services that the individual will perform as Facility Director are separate and apart from those performed in the individual's role as a foreign official. The DOJ noted that the official will not perform any services on behalf of, or receive any direction from, the Requestor, and the official will have no decision-making authority over matters affecting the Requestor, including any procurement or contracting decisions.

Noteworthy Aspects:

- Not all Transactions with Foreign Officials Banned: Although the status of the employee as a foreign official is a red flag under the FCPA, the opinion release shows that not all transactions with foreign officials are banned under the Act. The DOJ highlighted several factors that appeared to absolve the company of liability under the FCPA, including the Requestor's contractual obligation to hire the official pursuant to an agreement between the U.S. government and the foreign country, the Requestor's lack of participation in the selection process, the fact that the individual's duties as a foreign official did not intersect with those performed as Facility Director, and the official did not hold any potential influence on the Requestor through those duties.

On May 25, 2010, DOJ Acting Deputy Attorney General Gary Grindler issued additional guidance for prosecutors relating to the use of independent corporate monitors in deferred prosecution and non-prosecution agreements ("DPAs and NPAs" or "agreements"). According to a November 2009 Government Accountability Office ("GAO") report, 48 of the 152 agreements negotiated by the DOJ from 1993 through September 2009 have required appointment of a monitor. As noted by the GAO in a December 2009 report, the 2008 Morford Memorandum has governed the DOJ in the selection and use of independent monitors without providing adequate guidance for companies concerned about monitors' cost, selection, independence, and responsibilities, and about seeking DOJ assistance to resolve those concerns. As a result, the December 2009 report recommended that the DOJ develop performance measures to assess the effectiveness of DPAs and NPAs. The DOJ agreed with that recommendation.

In accordance with the GAO recommendation, the DOJ issued a new basic principle addressing the DOJ's role in resolving monitorship disputes. The principle states that a DPA or NPA "should explain what role the Department could play in resolving disputes that may arise between the monitor and the corporation, given the facts and circumstances of the case." As explained in the comment to the new principle, clear communication between prosecutors and the companies under monitorship should improve the DOJ's ability to receive notice of monitorship disputes, improve public confidence in the use of monitors, and increase monitors' accountability. Generally, the DOJ's role in resolving disputes with monitors should be limited to questions about the company's compliance with the monitor agreement but in practice will depend on the specific public and law enforcement interests at issue.

The new principle suggests that prosecutors should consider whether the following language should be included in DPAs or NPAs:

- With respect to any Monitor recommendation that the company considers unduly burdensome, impractical, and unduly expensive, or otherwise inadvisable, the company need not adopt the recommendation immediately; instead, the company may propose in writing an alternative policy, procedure, or system designed to achieve the same objective or purpose. As to any recommendation on which the company and the Monitor ultimately do not agree, the views of the company and the Monitor shall promptly be brought to the attention of the Department. The Department may consider the Monitor's recommendation and the company's reasons for not adopting the recommendation in determining whether the company has fully complied with its obligations under the Agreement.

- At least annually, and more frequently if appropriate, representatives of the company and the Department will meet together to discuss the monitorship and any suggestion, comments, or improvements the company may wish to discuss with or propose to the Department, including with respect to the scope or costs of the monitorship.

International Developments

Multilateral Development Banks Sign Cross-Debarment Agreement

On April 9, 2010, five multilateral development banks ("MDBs") signed an agreement to mutually enforce debarment against any firm or individual debarred by one of the banks. The World Bank and four regional development banks -- the African Development Bank, the Asian Development Bank, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, and the Inter-American Development Bank Group -- agreed to cross-debar entities debarred by one of the signatory banks for corruption in an MDB-financed development project.

Under the agreement, a firm debarred for more than one year by any of the participating banks will be debarred from conducting business with all five of the banks. Mutual enforcement is subject to the criteria that the sanctioning institution makes the initial debarment public, the initial debarment decision is made after the cross-debarment has entered into force with respect to the sanctioning institution, the debarment decision is made within ten years of the date of the misconduct, and the decision is not made in recognition of a decision in a national or international forum. The agreement contains a limiting clause stating that a participating bank may decide not to enforce a debarment decision where such debarment would be inconsistent with its legal or other institutional considerations. However, the agreement also provides for wider enforcement of cross-debarment procedures by welcoming other international financial institutions to join the agreement after its entry into force.

World Bank Debars MacMillan Publishers

On April 30, 2010, the World Bank announced that it had debarred Macmillan Publishers, Limited ("Macmillan") for a period of six years based on the company's admission that a subsidiary paid bribes in an unsuccessful bid for a World Bank contract in southern Sudan. The original debarment period of eight years was reduced to six years in recognition of Macmillan's "early acknowledgement" of the issue to the World Bank.

Macmillan, a privately-owned company based in the United Kingdom, admitted that a subsidiary of its education business, Macmillan Education, paid bribes to secure a World Bank education contract in southern Sudan. The World Bank administers the Sudan Multi-Donor Trust Fund ("MDTF"), which was established in 2006 to fund post-conflict reconstruction in southern Sudan. The bribes were reportedly paid to a local official between 2008 and 2009 in an unsuccessful attempt to win a multi-million pound contract to publish textbooks for an MDTF education rehabilitation project.

Macmillan self-reported the improper payments to the World Bank and entered a settlement agreement in exchange for a reduced debarment period. As part of its agreement with the Bank, the company announced that it would implement a compliance program and hire a monitor to ensure the adequacy of the program. While the agreement stipulates that Macmillan is ineligible to bid for World Bank contracts for the next six years, the debarment period may be further reduced to three years subject to the company's continued cooperation with the Bank.

In a press release on May 6 announcing the settlement, Macmillan stated that it has conducted a review of Macmillan Education's practices and procedures and has started implementation of a revised ethical framework to include comprehensive risk assessment and staff training. The company has also established a board-level Risk and Compliance Committee in its efforts to prevent the recurrence of improper conduct. Macmillan confirmed that it has voluntarily disclosed the matter to the U.K.'s Serious Fraud Office.

United Kingdom

The U.K. Parliament passed the U.K. Bribery Act 2010 (the "U.K. Bribery Act") on April 8, 2010, significantly reforming the country's anti-bribery laws. U.K. Government guidance on the U.K. Bribery Act has been scheduled to be published by July 2010. The U.K. Bribery Act is scheduled to be implemented in or about October 2010.

The U.K. Bribery Act bans both the payment and receipt of an "advantage" with the intention that a relevant "function or activity" will be performed "improperly." The provisions apply to both individuals and corporations, and also pertain to payments made by third parties. Significantly, a relevant function or activity includes both public functions and business activity, as the law covers both bribery of private citizens and public officials. The law applies a reasonable expectation test in assessing improper performance, which evaluates what a reasonable person in the United Kingdom would expect in relation to the function or activity in issue. Local custom or practice is to be disregarded unless it is permitted or required under local written law. Under the U.K. Bribery Act, individuals face up to ten years' imprisonment, a fine, or both for each violation. Corporations are subject to unlimited fines.

Payment of Bribes (Section One)

Under the U.K. Bribery Act, it is illegal for a person to offer, promise or give an "advantage" to another person with the intention of inducing a person to perform a function or activity improperly, or rewarding them for such improper performance. The provision applies to illegal offers made by third parties. The mere act of offering an advantage is an offense, regardless of whether the person to whom the advantage is offered takes action. Also, it does not matter if the advantage is offered to the same person who is to perform the act.

Receipt of Bribes (Section Two)

In addition to applying to individuals who offer bribes, the U.K. Bribery Act also applies to persons who receive such bribes. Under the U.K. Bribery Act, it does not mater whether a bribe recipient requests, agrees to receive, or accepts an "advantage" directly or through a third party, or whether the advantage is for the benefit of the recipient or another person. Moreover, the mere request, agreement or acceptance of an advantage constitutes the improper performance by the recipient of a function or activity. Also, it does not matter whether the person to whom the advantage is paid, or the individual who receives the improper advantage, knows or believes that the performance of the function or activity is improper.

Bribery of Foreign Public Officials (Section Six)

The U.K. Bribery Act contains a separate provision specific to bribery of foreign officials. Under the U.K. Bribery Act, it is unlawful to offer, promise or give any advantage, directly or through a third party, to a "foreign public official" with the intent to influence the official and obtain or retain business or an advantage. Under the U.K. Bribery Act, the foreign official must not be permitted nor required by local written law to be influenced in their capacity by the offer, promise, or gift. The term "foreign public official" is defined as an individual who holds any type of legislative, administrative, or judicial position; exercises a public function; or is an official or agent of a public international organization. The definition does not appear to include political candidates or employees of state instrumentalities, unless the employee exercises a "public function."

Senior Corporate Officers (Section 14)

If the payment or receipt of a bribe, or bribery of a foreign official, (Sections One, Two, and Six) are committed with the "consent or connivance" of a senior officer of a company, or a person purporting to act in such a capacity, both the senior officer or person, as well as the company, can be held liable if the senior officer or person has a "close connection" with the United Kingdom. Individuals with such a close connection would include U.K. citizens, U.K. nationals, and U.K. residents incorporated under U.K. law.

Corporations' Failure to Prevent Bribery (Section Seven)

One of the most significant provisions of the U.K. Bribery Act penalizes corporations for failing to prevent bribery. Under the U.K. Bribery Act, a "relevant commercial organization" is guilty of an offense if a person "associated" with the corporation bribes another person intending to obtain or retain business for the corporation or to obtain or retain an advantage in the conduct of business for the corporation. Persons associated with a corporation include employees, agents, subsidiaries, and others who perform services for or on behalf of a corporation.

The provision, though, contains an affirmative defense under which corporations may demonstrate that they had in place "adequate procedures" to prevent such conduct. The term "adequate procedures" is not defined in the U.K. Bribery Act; however, according to the U.K. Bribery Act, the Secretary of State must publish guidance about such procedures.

Territorial Application

Territorial application exists in relation to the payment and receipt of bribes, and bribery of public officials, (Sections one, two and six) if any part of the act takes place in the United Kingdom, or if the act occurs outside of the United Kingdom, but would be illegal if committed in the United Kingdom, and the person has a "close connection" with the United Kingdom. A close connection includes U.K. citizens, nationals and residents and companies incorporated under U.K. law.

Significantly, though, the provision regarding a corporations' failure to prevent bribery (Section Seven) applies not only to U.K. incorporated bodies and partnerships, but to a corporate body or partnership which "carries on" a business, or part of a business, under U.K. law. Jurisdiction exists even if no part of the act was committed in the United Kingdom. The U.K. Bribery Act does not define what is entailed in carrying on a business in the United Kingdom.

Differences from the FCPA

As described above, the U.K. Bribery Act differs from the FCPA in several key ways:

Commercial Bribery: The U.K. Bribery Act prohibits bribery of both foreign officials and private citizens, wherever located. Thus, corporations could be liable if persons associated with the corporation, including third party agents, bribe a private citizen. The FCPA does not cover foreign commercial bribery.

No facilitating payments exception: Unlike the FCPA, the U.K. Bribery Act does not have an exception for facilitating payments.

Jurisdiction: While the FCPA requires a territorial nexus for foreign companies to be held liable, the U.K. Bribery Act does not require such a nexus for foreign companies which fail to prevent bribes. Under the U.K. Bribery Act, a non-U.K. corporation can be held liable for failing to prevent bribery if they carry on a business, or part of a business, in the United Kingdom, regardless of where the allegedly illegal acts took place. As described above, though, it is a defense for corporation to have in place adequate compliance programs.

Reasonable and bona fide business expenses: Unlike the FCPA, the U.K. Bribery Act does not include a defense for reasonable and bona fide business expenses directly related to promotional activities.

Adequate procedures defense: The U.K. Bribery Act contains an affirmative defense for having "adequate procedures" in place to prevent bribery. No such defense exists under the FCPA, although it is a mitigating factor in the Sentencing Guidelines and agency guidance.

Foreign officials: While the FCPA's definition of "foreign official" includes an "employee of a foreign government or any department, agency or instrumentality thereof," the U.K. Bribery Act is not as clear as to inclusion of low-level officials. Under the U.K. Bribery Act, the definition of "foreign public official" includes an individual who "holds a legislative, administrative or judicial position of any kind, whether appointed or elected;" exercises a public function for, or on behalf of, a foreign government or agency; or is public international organization official or agent.

Questions of Interpretation and Application

Although commentators and British law firms have emphasized the apparent breadth of the new U.K. Bribery Act, several questions about its scope and how it will be enforced are evident from the text of the statute and the commentary. For example:

- Does the absence of an affirmative defense for reasonable business promotional expenses mean that this law intends to prohibit such expenses, as some commentators fear?

- Does the absence of an explicit exception for facilitating payments mean that the U.K. Bribery Act prohibits the payment of facilitating payments (which the commentary to the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention suggests are not covered by the convention)?

- Will the guidelines on “adequate procedures” include a requirement that compliance programs prohibit or discourage facilitating payments in order to be “adequate”?

- Moreover, even if a corporation does have “adequate procedures,” which would be an affirmative defense to the Section 7 “failure to prevent bribery” prohibition, will the corporation be subject to prosecution under the general Section 6 prohibition against bribery and, if not, will not the “adequate procedures” defense largely immunize corporations from prosecution as a practical matter?

- Finally, to what extent will the apparently expansive jurisdictional reach of the new law extend to a non-U.K. company that does business in the United Kingdom, but pays a bribe outside of the U.K. with no connection to the U.K.? And, if so, would asserting jurisdiction in those circumstances be contrary to established principles of international law?

Miller & Chevalier will continue to monitor developments in this area and issue additional alerts as appropriate.

Executive of Johnson & Johnson Unit Jailed for Role in Greek Healthcare Corruption

On April 14, 2010, the U.K.'s Serious Fraud Office ("SFO") announced that Robert John Dougall, a former executive of a subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson (DePuy International Limited, or "DPI"), pleaded guilty at Southwark Crown Court to charges related to his involvement in the bribery of Greek surgeons by DPI. Specifically, according to the SFO release, from 2002 to 2005, DPI paid approximately £4.5 million to a Greek distributor, Medec S.A. and a related company, with the understanding that the distributor would use a portion of the payments to induce or reward surgeons to use DPI orthopedic products. DPI referred to the improper payments variously as advance "commissions," "cash incentives," and "Professional Education." The funds available for the corrupt payments amounted to 20% of the value of end-user sale price. Dougall served as Director of Marketing at DPI, and had responsibility for business development in Greece. The press release does not provide details regarding Dougall's involvement in the scheme, merely stating that he "acted to carry out the corporate intention of DPI." Dougall received a prison sentence of 12 months, which was reduced on appeal to a 12 month suspended sentence.

Notably, the press release does not specifically state whether U.K. authorities consider the Greek surgeons to be officials of the Greek government. Indeed, the statute Dougall is charged with violating (§ 1 of the Prevention of Corruption Act of 1906) does not require that recipients of bribes be affiliated with a government. Rather, the statute prohibits the bribery of "agents." The press release describes the bribe recipients as "agents of the Hellenic Republic, namely medical professionals working within the public healthcare system in the Hellenic Republic." It also states that the effect of the scheme was that the "Greek taxpaying public funded the corrupt payments." Thus, while it is unknown whether the surgeons were considered employees of a state entity, it appears that they were at least agents of the government and carried out a public function.

Additionally, Dougall's sentencing and appeal may have implications for the SFO's ability to enter into future U.S.-style plea agreements with cooperating defendants. In this case, the SFO noted that Dougall cooperated fully with and provided substantial assistance to the SFO. Indeed, the SFO noted that Dougall is the "first co-operating defendant in a major SFO corruption investigation." According to press accounts, because of Dougall's cooperation, the SFO had requested a suspended sentence. However, in Southwark Crown Court ("lower court"), Mr. Justice Bean imposed a 12 month sentence, reportedly concluding that public policy considerations did not justify a suspended sentence. The lower court's unwillingness to consent to the SFO's requests for leniency is similar to views expressed by Lord Justice Thomas in the March 2010 sentencing judgment for Innospec, Ltd. ("Innospec"), as reported in our FCPA Spring Review 2010. In that sentencing judgment, Lord Justice Thomas held that the SFO had no power to enter into a U.S.-style plea agreement with Innospec, and that "it is for the court to decide on the sentence and to explain that to the public." Here (unlike in Innospec) the lower court imposed a harsher sentence than the SFO requested. The Court of Appeal, however, suspended Dougall's sentence, but reportedly warned that suspended sentences would not automatically be imposed for cooperating witnesses. In sum, the result of Dougall is similar to that of Innospec; the SFO's requested sentence was ultimately imposed, but with accompanying statements that may deter future potential cooperating witnesses.

France

Total S.A. under Investigation

On April 6, 2010, a French court placed French oil giant Total S.A. under investigation for corruption in connection with the United Nations "Oil-for-Food" program ("OFFP") in Iraq. The French company, one of the six largest non-state-owned energy companies in the world, is headquartered in Courbevoie, France and listed on the New York Stock Exchange. According to press reports, politicians allegedly received vouchers for oil in exchange for lobbying to loosen sanctions on Saddam Hussein's regime and Total employees bought the oil.

According to Total's 2009 annual report, the CEO and several other current or former employees were formally investigated by French authorities beginning in 2006 for possible charges as accessories to the misappropriation of corporate assets and as accessories to the corruption of foreign public agents. In 2009, the Prosecutor's office recommended dismissing the case against all current and former employees. In early 2010, a new investigating judge decided to put the company under investigation for bribery, complicity, and influence peddling. Total states in the annual report that the formal investigation does not involve any new evidence and Total believes it was in compliance with OFFP.

Germany

No Jail for Convicted Siemens Execs

On April 19, 2010, two former Siemens AG executives, Michael Kutschenreuter and Hans-Werner Hartmann, were convicted by a Munich court for breach of trust and abetting bribery in connection with the massive scandal that has plagued the company in recent years (see Siemens Alert). The pair allegedly helped cover up slush funds and bribes paid by Siemens telecommunications arm to secure contracts in Russia and Nigeria.

Kutschenreuter, a former Financial Director at Siemens, received a two-year suspended sentence, was fined €61,000, and ordered to pay an additional €100,000 to charity. While Hartmann, another executive, received an 18-month suspended sentence and was required to pay €40,000 to charity.

Several other former Siemens executives have been convicted in the wake of the bribery scandal and all have likewise received suspended sentences. Kutschenreuter and Hartmann, however, reportedly could be the last two individuals tried in connection with the long-running scandal, as the hundreds of other individuals still under investigation are expected to receive summary punishments. To date, no individuals connected with the Siemens scandal have been charged in the United States.

German Companies Make Anti-Corruption Pledge

On April 21, 2010, more than fifty German companies that conduct business in Russia, including Daimler AG, Deutsche Bank AG, Deutsche Bahn AG and Siemens AG, promised not to offer bribes in their business dealings in Russia. The companies, which are members of the Russian-German Chamber of Commerce ("RGVP"), initiated the pledge themselves and entered into it at an official ceremony in Moscow, with a top Russian Presidential aide Arkady Dvorkovich in attendance.

Participating companies signed both the International Business Leaders Forum's ("IBLF") Corporate Ethics Initiative for Business in the Russian Federation and World Economic Forum's Partnering against Corruption - Principles for Countering Bribery. By committing themselves to these initiatives, participating companies specifically agreed to implement the proscribed anti-bribery and anti-corruption principles and practices or use them as benchmarks to improve their existing programs.

In determining how to most effectively implement anti-corruption programs in Russia, RGVP Chairman Michael Harms said member companies decided the mutual pledge would be a critical step: "If companies announce they do not intend to bribe anymore, it can be expected that no one will turn to them for bribes."

The pledge was lauded by a wide-range of organizations, including The International Business Forum, the American Chamber of Commerce, the European Business Association, and the Russian Government.

Ferrostaal AG under Investigation

German prosecutors have reportedly initiated an investigation of German engineering company Ferrostaal AG and roughly a dozen of its executives over long-running bribery allegations. At least two executives, including Board member Klaus Lesker, have been arrested as a result of the probe. The investigation is said to be focused on five projects worth a combined €1 billion that were purportedly secured through illicit payments

The current investigation is fallout from the ongoing investigation of Ferrostaal's former parent company (and current minority stakeholder), MAN SE. Last summer, German authorities raided Ferrostaal offices as part of that inquiry. The allegations against Ferrostaal are extensive and relate to an €880 million (about $1.1 billion) submarine contract with Portugal that the Company secured in November 2003. Ferrostaal allegedly obtained the contract in part by promising a Portuguese diplomat, who the Company hired as a "consultant," a cut of the contract (around €1.6 million, or about $2.0 million) for his help in setting up a meeting with the Portuguese Prime Minister. Ferrostaal is also believed to have entered into numerous other sham consulting agreements related to the submarine deal, which included large payments to a Portuguese law firm and more than €1 million (or about $1.3 million) to an admiral in the Portuguese navy.

Beyond bribes to secure contracts for itself, Ferrostaal is also alleged to have arranged bribe payments for others in exchange for a fee. Specifically, it is alleged that Ferrostaal used bribes, through a consultant, to organize the sale of several printing and embossing machines to a state-owned Indonesian company on behalf of the German firm Giesecke & Devrient. The Company is also purported to have brokered sales for another German company to the Colombian navy and the Argentine Coast Guard by making illicit payments to defense officials.

The Ferrostaal investigation is just the latest in a string of corruption-related investigations by German authorities, which include probes against Siemens AG, MAN SE, and Giesecke & Devrient GmbH.

Canada

Canadian Citizen Arrested and Charged Under the Corruption of Foreign Public Officials Act

On May 27, 2010, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police ("RCMP") "A" Division International Anti-Corruption Unit ("IACU") arrested and charged Nazir Karigar, a Canadian Citizen, with one count of corruption under Section 3(1)(b) of the Corruption of Foreign Public Officials Act ("CFPOA"). According to a RCMP press release, the IACU acted on information it received in 2007 indicating that representatives of a Canadian company made a payment to an Indian government official in order to facilitate the execution of a multi-million dollar contract for the supply of a security system. While the RCMP has declined to disclose the company for which Nazir Karigar worked at the time of the alleged violation, press accounts indicate that Cryptometrics, a high-tech firm that develops facial recognition software for airports and governments internationally, employed Karigar. Cryptometrics is an Ottawa firm that is headquartered in Tuckahoe, New York.

The information contained in this communication is not intended as legal advice or as an opinion on specific facts. This information is not intended to create, and receipt of it does not constitute, a lawyer-client relationship. For more information, please contact one of the senders or your existing Miller & Chevalier lawyer contact. The invitation to contact the firm and its lawyers is not to be construed as a solicitation for legal work. Any new lawyer-client relationship will be confirmed in writing.

This, and related communications, are protected by copyright laws and treaties. You may make a single copy for personal use. You may make copies for others, but not for commercial purposes. If you give a copy to anyone else, it must be in its original, unmodified form, and must include all attributions of authorship, copyright notices, and republication notices. Except as described above, it is unlawful to copy, republish, redistribute, and/or alter this presentation without prior written consent of the copyright holder.