Trade Compliance Flash: Key Take-Aways from the EAPA Investigations by U.S. Customs and Border Protection

International Alert

It has been just over two years since the enactment of the Trade Facilitation and Trade Enforcement Act of 2015 (TFTEA), a law designed to enhance and streamline U.S. Customs and Border Protection's (CBP) capabilities, and to make CBP more responsive to, and collaborative with, the importing community. Included in TFTEA was the Enforce and Protect Act of 2015 (EAPA), which established a formal process for private parties to request that CBP investigate claims of evasion of antidumping and countervailing duty (AD/CVD) orders. CBP previously accepted allegations of evasion, but the agency was never required to initiate investigations, nor was it required to inform the parties that submitted allegations of any enforcement steps taken. In contrast, under EAPA, CBP is required to take certain actions within specified time frames (e.g., CBP must conclude most investigations within 300 days), the parties that file the allegations have an opportunity to participate in the investigation, and CBP is obliged to inform the parties to the investigation of key developments (e.g., initiation and evasion determinations).

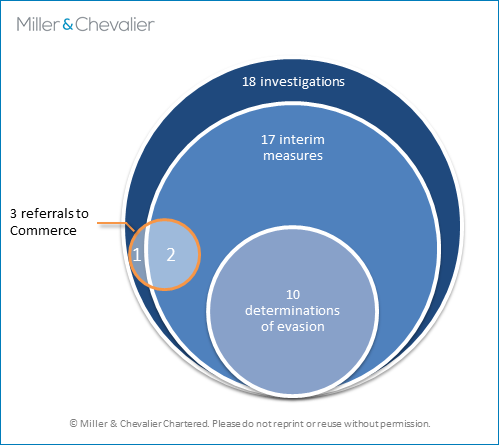

Since EAPA's enactment in February 2016, CBP has publicly announced the initiation of 18 AD/CVD evasion investigations stemming from allegations submitted through the EAPA process. Of those investigations, 10 have resulted in final determinations of duty evasion by CBP. Importers found to be evading an AD/CVD order are liable for the unpaid AD/CVD duties and may be subject to serious financial penalties and criminal prosecution. CBP can take additional enforcement measures, including referring the matter to other agencies – such as Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) – for possible civil or criminal investigation.

In short, EAPA allegations have proven to be an effective avenue of self-help for those harmed by AD/CVD evasion, and represent an increase in potential liability for importers who are wittingly or unwittingly involved in such evasion. Below is a breakdown of EAPA investigations to date, along with major trends and takeaways.

Background on EAPA

19 U.S.C. § 1517(a)(5)(A) defines "evasion" as entering merchandise subject to AD/CVD orders by means of an act or omission that is material and false, and which results in AD/CVD duties being reduced or not collected. Examples of evasion include the misrepresentation of the merchandise's true country of origin (e.g., through fraudulent country of origin markings on the product itself or false sales), false or incorrect shipping and entry documentation, using the wrong tariff subheading or mischaracterizing the merchandise's physical characteristics.

Either an "interested party" or another federal government agency, such as the Department of Commerce, can file an EAPA allegation using CBP's online e-Allegation portal. An "interested party" is defined broadly to include importers and foreign manufacturers, U.S. manufacturers, labor unions and trade associations. Once an interested party submits an EAPA allegation, CBP has 15 business days to determine whether or not to initiate an investigation. CBP will initiate an investigation if the allegation reasonably suggests: (1) that merchandise subject to an AD/CVD order entered the United States, and (2) it was entered through evasion.

In the event that CBP cannot determine whether the merchandise described in an allegation is properly within the scope of an AD/CVD order, CBP will refer the question to the Department of Commerce. Such a referral tolls the clock with regard to investigative deadlines outlined in EAPA, providing the Department of Commerce with the necessary time to conduct its analysis and determine whether the merchandise at issue is within the scope of an AD/CVD order. The ultimate findings of the Department of Commerce will be added to the administrative record of the case.

To investigate allegations of evasion, CBP has a variety of tools at its disposal. First and foremost, CBP utilizes data analytics to its record, collected through Automated Commercial Environment (ACE), of a company's import transactions. CBP can also issue questionnaires to the importer, foreign producer, and other interested parties, as well as conduct inspections of imported merchandise. In addition, CBP has utilized it attachés in foreign countries and has partnered with foreign customs and law enforcement agencies to conduct overseas investigations to further develop facts that could support or refute allegations of evasion.

Throughout an EAPA investigation, both the party that submitted the allegation and the importer are able to supply additional facts, arguments, and rebuttals for the administrative record. Because evasion determinations in EAPA investigations are based entirely on the administrative record, this process of providing supplemental information can be critical to the outcome and CBP's determination.

Within 90 days of initiating an EAPA investigation, CBP will make an interim decision as to whether there is "reasonable suspicion" that merchandise covered by an AD/CVD order was entered into the United States through evasion. In cases where CBP determines there is reasonable suspicion of evasion, the regulations state that CBP will: (1) suspend the liquidation of unliquidated entries of the covered merchandise entered after the date of initiation; (2) extend the period for liquidating the unliquidated entries of covered merchandise that entered before the initiation of the investigation; and (3) take any additional measures necessary to protect the ability to collect appropriate duties, which may include requiring a single transaction bond or posting cash deposits or reliquidating entries as provided by law with respect to entries of the covered merchandise. These measures are imposed to ensure CBP collects the appropriate duties while it completes the EAPA investigation.

No later than 300 days from the initiation of the investigation (360 days in "extraordinarily complicated" cases), CBP must make a determination as to whether, based on "substantial evidence," evasion has occurred. The consequences of an affirmative evasion determination can be severe. An importer found to be evading an AD/CVD order will be liable for the unpaid AD/CVD duties for as much as the previous five years, plus a penalty, and will be required to post cash deposits on future entries of the covered merchandise. CBP can take additional enforcement measures, including referring the matter to other agencies – such as ICE – for possible civil or criminal investigation. CBP will issue a notice of a final determination within five business days of the decision.

EAPA by the Numbers

Since the enactment of EAPA, CBP has made public 18 AD/CVD evasion investigations targeting a broad range of industries and has issued final determinations of evasion with regard to 10 importers. The steel industry has led the pack in terms of EAPA allegations, submitting 10 EAPA allegations that have all led to final determinations of evasion. However, EAPA allegations from manufacturers and trade groups related to the chemical, furniture, aluminum, and diamond sawblade industries have also led to investigations and interim measures.

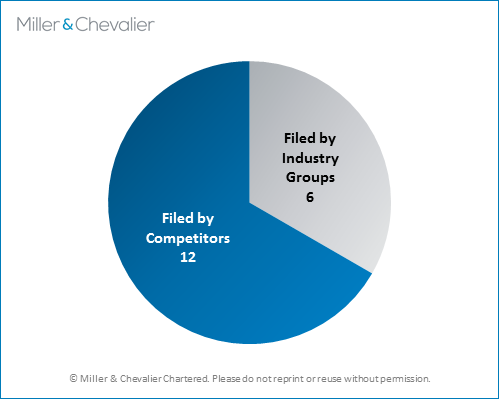

Of these 18 investigations, 13 involved transshipment, one involved the obfuscation of the manufacturer within the country of origin, and four involved misclassification. Of the 18 investigations, 17 involved goods of Chinese origin. Based on public information, both competitors and industry groups have submitted EAPA allegations that led to investigations, with competitors filing 12 and industry groups filing six.

CBP is not required to provide public notice in those instances in which it does not initiate an EAPA investigation. However, considering that the first public EAPA notification was one declining to initiate an EAPA investigation, it is notable that no further declinations have been published. It may be the case that CBP simply feels that additional non-initiation notices would not substantively inform the trade community with regard to what CBP is looking for in an EAPA allegation.

Takeaways from CBP's Responses to EAPA Allegations

- Allegations Must Show Evidence of Imports of the Subject Merchandise. To reasonably suggest evasion, the allegations must contain evidence that the subject merchandise is actually being imported. In the allegations that have led to investigations, this evidence has come in the form of records collected and produced by business intelligence platforms – such as Panjiva and Import Genius – that provide subscribers with import/export data based on information collected from ocean bills of lading. This information can include merchandise descriptions, classification codes, weight, and the number and size of containers, among other details. In one EAPA investigation, the allegation relied on comparisons of import weights to suggest to CBP that diamond sawblades were being imported as millstone segments in order to evade anti-dumping duty (ADD) deposit requirements on diamond sawblades. In another, samples of the product were purchased by the alleging party to obtain information relating to the country of origin and price of the imports to reasonably suggest ADD deposits were not being made.

- Most Successful EAPA Allegations Have Involved Transshipment. Of the 18 EAPA allegations publicly known to have led to investigations, 13 have involved transshipment of merchandise. In each of these cases, the goods were alleged to have been of Chinese origin and exported to a third country prior to importation into the United States in an effort to obscure the country of origin of the goods and avoid ADD deposit requirements. Similarly, one allegation claimed that a Chinese furniture manufacturer sold merchandise through a second Chinese party to obscure the furniture's origins because of the manufacturer's relatively higher ADD rate. Only four of the public allegations have involved allegations of misclassifying merchandise. This trend toward allegations of transshipment could indicate that evidence reasonably suggesting evasion is easier to obtain in cases of transshipment than in cases of alleged evasion through other means, and/or that transshipment is the preferred method of AD/CVD evasion.

- Investigative Reports Boost Allegations Chances of Success. The 13 EAPA allegations of evasion through transshipment have all included reports on the foreign exporters, commissioned by the alleging parties. In these cases, investigators have conducted site visits to the foreign entities alleged to be involved in the transshipment in order to collect evidence in support of the allegation. These investigators have been able to provide pictures of facilities, observations of employees, and financial information gathered during the course of the investigation. Such information can show that foreign facilities do not have the capacity to produce the quantity of goods that the facility is exporting to the United States, suggesting transshipment. In one case, the investigator was able to obtain financial information allegedly showing that the foreign party had not purchased the manufacturing equipment necessary to produce the wire garment hangers it claimed to be making, painting a convincing picture of evasion for CBP. In another, investigators appear to have contacted a Chinese freight forwarder, posing as individuals seeking to illicitly transship goods, to obtain information critical to the evasion allegation. Based on CBP's public responses to these allegations, such investigations and site visit reports play an important role in reasonably suggesting that AD/CVD evasion is occurring.

- CBP Will Seek Scope Rulings from Department of Commerce. In the case of three EAPA allegations, CBP has sought scope rulings from the Department of Commerce to determine whether the subject merchandise was covered by the scope of an AD/CVD order. In two of these cases, CBP requested scope rulings after it had imposed interim measures. In the third case, which involves imports of a generic version of a refrigerant, both CBP and the alleging party have sought scope determinations related to the imports.

- Importers Can Be Unwitting Parties to Evasion. In the first final determination of evasion issued by CBP stemming from an EAPA allegation, CBP made clear that the statutory definition of evasion focuses solely on whether adequate deposits or bonds were submitted. In that case, the importer found to have engaged in evasion claimed it had not known of the transshipment scheme and that it was merely an unwitting importer. However, CBP stated that whether the importer is a knowing and active participant in the evasion scheme is not determinative of whether evasion has occurred, though it will likely be important for the purpose of determining whether the government pursues civil or criminal penalties.

Conclusion

While 2016 may have been the warmup lap for EAPA, it has been less than two years since CBP initiated the first EAPA investigation and the law is already proving to be an accessible and effective tool for private parties, though one that requires thoughtfulness and creativity to produce results. As more companies come to recognize the potential that submitting an EAPA allegation has for leveling the playing field, and as the Trump administration continues its efforts to crack down on unfair trade practices, we expect this trend to continue and to see additional EAPA investigations and final determinations in 2018 and into the future.

For more information, please contact:

Richard A. Mojica, rmojica@milchev.com, 202-626-1571

Patrick M. Stewart, pstewart@milchev.com, 202-626-1582

Reproduced with permission from Copyright 2018 The Bureau of National Affairs, Inc. (800-372-1033) www.bna.com.

The information contained in this communication is not intended as legal advice or as an opinion on specific facts. This information is not intended to create, and receipt of it does not constitute, a lawyer-client relationship. For more information, please contact one of the senders or your existing Miller & Chevalier lawyer contact. The invitation to contact the firm and its lawyers is not to be construed as a solicitation for legal work. Any new lawyer-client relationship will be confirmed in writing.

This, and related communications, are protected by copyright laws and treaties. You may make a single copy for personal use. You may make copies for others, but not for commercial purposes. If you give a copy to anyone else, it must be in its original, unmodified form, and must include all attributions of authorship, copyright notices, and republication notices. Except as described above, it is unlawful to copy, republish, redistribute, and/or alter this presentation without prior written consent of the copyright holder.