Buckle Up: Treasury and IRS Publish Final Section 30D Regulations on Consumer Clean Vehicle Credit

Tax Alert

"Everything in life is somewhere else," E.B. White said, "and you get there in a car." The U.S. Department of Treasury (Treasury) and the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) just finalized regulations aimed at ensuring that car is powered by a battery (or maybe a hydrogen fuel cell).

The final regulations, which Treasury and the IRS published in the Federal Register on May 6, 2024, are under sections 25E and 30D of the Internal Revenue Code, which relate to the consumer vehicle credit for used and new vehicles, respectively. This alert focuses on section 30D, the new clean vehicle credit, rather than the credit for used clean vehicles under section 25E. The definitions in the section 30D regulations also impact the commercial clean vehicle credit of section 45W.

Background

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (IRA) overhauled the federal income tax credit for "new clean vehicles" in section 30D. Under the amended provision, purchasers of electric vehicles are eligible for a non-refundable federal income tax credit of up to $7,500, subject to several conditions, of which the most important are:

- The vehicle must be made by a "qualified manufacturer," which is a manufacturer that has registered and entered an agreement with the IRS to provide information on the new clean vehicles that it manufactures.1

- A certain percentage of the "applicable critical minerals" (ACMs) in the vehicle's battery by value must be extracted or processed either in the U.S. or in any country with which the U.S. has a free trade agreement (FTA) in effect, or be recycled in North America (the ACM Requirement).2 The required percentage increases over time; for vehicles placed in service in 2024, it is 50 percent.

- A certain percentage of the battery components in the vehicle's battery must be manufactured or assembled in North America (the Battery Component Requirement).3 The required percentage increases over time; for vehicles placed in service in 2024, it is 60 percent.

- The vehicle must not have any ACMs in its battery that were processed, extracted, or recycled by a "foreign entity of concern" (FEOC), beginning for vehicles placed in service in 2025 or later.4 Further, the vehicle must not have any battery components that were manufactured or assembled by a FEOC.5 (These two requirements are collectively the FEOC Restriction.) 42 U.S.C. § 18741(a)(5) defines FEOC as entities that are "owned by, controlled by, or subject to the jurisdiction or direction of a government of a foreign country that is a covered nation." "Covered nation" means Russia, North Korea, China, and Iran.6

Section 30D(g) allows taxpayers to elect to "transfer" their credit to the car dealer in exchange for cash or down payment assistance. The dealer then claims the credit and is eligible to receive the credit in advance of filing its return, provided it is properly registered to do so.

The regulations represent the finalization of three separate packages of proposed regulations: (1) the April 17, 2023, proposed regulations (88 Fed. Reg. 23370) defining some key terms and proposing guidance for the ACM Requirement and the Battery Component Requirement; (2) the October 10, 2023, proposed regulations (88 Fed. Reg. 70310) that provided guidance on the advanced payment and transfer provision; and (3) the December 4, 2023, proposed regulations (88 Fed. Reg. 84098) on the definition of "qualified manufacturers" and the FEOC rules (Treas. Reg. § 1.30D-6), which were concurrent with proposed Department of Energy (DOE) guidance on FEOC definitions (88 Fed. Reg. 84082). Concurrent with these finalized regulations, the DOE also finalized interpretive rules relating to the pertinent FEOC definitions.

Transfer Rules: Addressing Non-Refundability

The final regulations largely adopted the proposed regulations on taxpayer elections to transfer the section 30D(g) credit to a dealer and the dealer's ability to receive an advance payment of the transferred credit. If an irrevocable transfer election is made, the dealer must pay to the taxpayer the entire amount of the section 30D credit (e.g., $7,500) either in cash or in the form of a partial payment or down payment or reduction in sales price for the purchase of a new clean vehicle.7 This payment is not includable in the gross income of the taxpayer and is treated as an amount realized when repaid by the electing taxpayer to the dealer for purposes of section 1001 in determining the dealer's gain or loss on the vehicle.8

Significantly, the final regulations are clear that "[t]he credit amount under section 30D that the electing taxpayer elects to transfer to the eligible entity [dealer] under section 30D(g)…may exceed the electing taxpayer's regular tax liability…for the taxable year in which the sale occurs, and the excess, if any, is not subject to recapture on the basis that it exceeded the electing taxpayer's regular tax liability."9 Thus, the final regulations confirm that the election under section 30D(g) might provide an end-run around the general rule of non-refundability for the section 30D credit (that is, if no election is made, the credit is only available to the extent of the taxpayer's regular tax liability).

ACM Requirement: A "More Stringent" Approach, But a Generous Transition Rule

The April 2023 proposed regulations adopted a "50 Percent Value Added" test with respect to the ACM Requirement. The test used a 50 percent threshold to determine whether an ACM was a qualifying critical mineral, that is, an ACM was treated as extracted or processed in the U.S. or an FTA country if 50 percent or more of the value added to the ACM by extraction was derived from extraction that occurred in the U.S. or an FTA country, or 50 percent or more of the value added to the ACM by processing is derived from processing that occurred in the U.S. or an FTA country.10

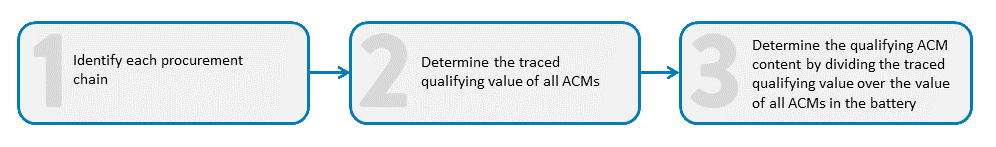

The final regulations adopt a "Traced Qualifying Value Test," which the preamble states is both "more precise" and "more stringent" than the 50 Percent Value Added test from the proposed regulations. This test, which, like the 50 Percent Value Added test, must be done separately for each ACM procurement chain, can be summarized as follows:

- The qualified manufacturer determines each procurement chain.

- The qualified manufacturer determines the "traced qualifying value" of all ACMs in the chain. This is the value of the ACM multiplied by the greater of (A) the value added by extraction that occurred in the U.S. or an FTA country, divided by the total value added from extraction of the ACM, or (B) the value added to the ACM by processing that occurred in the U.S. or an FTA country, divided by the total value added from processing the ACM. With respect to recycled ACMs, it is the value of ACM multiplied by the percentage obtained by dividing the value added to the ACM by recycling that occurred in North America by the total value added by recycling. The sum of these figures for all ACMs contained in the battery is the "total traced qualifying value."

- The qualified manufacturer determines the qualifying ACM content by dividing the "total traced qualifying value" from step 2 by the value of all ACMs contained in the battery.

Under the final regulations, the qualified manufacturer must determine the applicable values above at some point after the final processing or recycling of the ACMs.11 Qualified manufacturers can apply the ACM test either by looking at the batteries in specific vehicles (that is, on a vehicle-by-vehicle basis) or taking the average over a "specified period of time" (the final regulations suggest a year, quarter, or month) with respect to vehicles from the same line, plant, class, or some combination.12 Thus, there appears to be some flexibility as to how the qualified manufacturer applies the ACM Requirement to a fleet of vehicles.

Further, the final regulations allow qualified manufacturers to continue to use the 50 Percent Value Added test through 2026 as a form of transition relief.13

Battery Component Requirement: Stay the Course

Unlike with respect to the ACM Requirement, the final regulations largely adopt the proposed regulations' approach to the battery component test without change, though they did clarify the definition of "battery components." A battery component is defined as a component that forms part of a battery and that is manufactured or assembled from one or more components or battery materials that are combined through industrial, chemical, and physical assembly steps. Battery components include a cathode electrode, anode electrode, solid metal electrode, coated separator, liquid electrolyte, solid state electrolyte, battery cell, and battery module.14

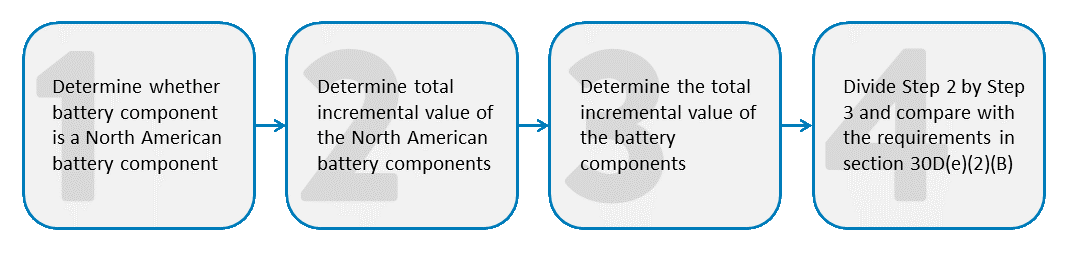

The four-step process for applying the battery component test under the final regulations is as follows:

- The qualified manufacturer must determine whether each battery component is a "North American battery component," that is, a battery component substantially all of the manufacturing or assembly of which occurs in North America.

- The qualified manufacturer must determine the total incremental value of North American battery components, which is the sum of the incremental values of each North American battery component contained in the battery.

- The qualified manufacturer must determine the "total incremental value of the battery components," which is the sum of the incremental values of each battery component in the battery (whether or not a North American battery component).

- The qualified manufacturer must divide the result in step 2 by the result in step 3, and see if the quotient meets the requirement set forth in section 30D(e)(2)(B) (i.e., 60 percent for vehicles placed in service in 2024).15

Similar to the ACM test, the qualified manufacturer can run the battery component test either by a specific vehicle, or use an average computed over a "limited period of time" (for example, a year, quarter, or month) with respect to vehicles from the same model, line, plant, class, or some combination thereof with final assembly in North America.16

Foreign Entities of Concern: Also Familiar, but with Some Welcome Changes

The DOE Final Interpretive Rule that identifies the foreign entities that qualify as FEOCs as a result of being "owned by, controlled by, or subject to the jurisdiction or direction of a government of a foreign country that is a covered nation" was eagerly anticipated. The final rule generally follows the December 2023 proposed rule with a few clarifications.

The preamble to the final rule is full of examples and explanations that should be useful to qualified manufacturers trying to determine whether any of the foreign entities in their battery supply chains are FEOCs and would therefore bump them out of compliance with the FEOC Restriction of section 30D(d)(7). A few notable highlights include:

- The preamble confirms that the "jurisdiction" standard is an objective standard applying U.S. definitions and not a subjective standard that follows the definitions used by covered nations. It is also broad, applying to entities that are organized under the legal provisions of the covered nation as well as entities that operate within the borders of the nation.17

- A subsidiary of a U.S.-headquartered company that is located in a covered nation is likely going to meet this standard and be an FEOC, as it will likely be organized under the laws of the covered nation or operating within the borders of the covered nation. This designation will not flow back to the U.S. entity's operations in the U.S. or other countries, however.18

- The subsidiaries of an FEOC that are located outside of a covered nation are not automatically deemed FEOCs. However, a government of a covered nation cannot evade the FEOC restriction simply by establishing a U.S. subsidiary while otherwise maintaining ownership or control.19

Many comments on the proposed DOE rule asked DOE to provide more concrete guidance on certain issues (e.g., an exhaustive list of which "senior government officials" are considered part of the "government of a foreign country"). DOE generally rejected this invitation in favor of broader, less defined standards that would bring a larger number of entities into the FEOC definition. This conservative approach is notable, as it gives DOE greater flexibility to address unique facts and circumstances as they arise and prevent gamesmanship by FEOCs trying to avoid being branded as such.

DOE clarified how to calculate whether the ownership interest of a government of a covered nation met the "25 Percent Ownership Threshold" for the underlying entity to be considered an FEOC.20 The 25 percent calculation applies to each ownership metric – an entity's voting rights, equity interests, or board seats – independently. For example, if a government of a covered nation holds 20 percent of an entity's voting rights, 10 percent of its equity interests, and 15 percent of its board seats, these percentages are not combined. Instead, the government is considered as having an interest equal to the highest metric (here, 20 percent).21 "Equity interests" include all ownership interests, including capital or profit interests and contingent equity interests.22

DOE slightly revised the safe harbor that allows non-FEOC entities to engage FEOC-contractors for certain activities without establishing "effective control" as long as certain rights are retained by the non-FEOC.23 The proposed rule included a requirement that intellectual property (IP) and technology subject to the contract be accessible to the non-FEOC "notwithstanding any export control or other limit on the use of intellectual property imposed by a covered nation subsequent to execution."24 Comments pointed out that this could be interpreted in a way that caused the non-FEOC to violate foreign law. The final rule adopted a more measured approach whereby the IP licenses only need to commit that the non-FEOC will retain access to and use of any IP "for the duration of the contractual relationship."25

DOE declined to create a voluntary pre-review process to review contracts with FEOCs to determine whether the contracts result in "effective control" under the final rule.26 DOE also declined to allow a transition period for determining whether the safe harbor might apply to contracts with FEOCs that existed prior to the IRA or the date of the final rule.27

Like the DOE final rule, the Treasury and IRS final regulations generally followed the December 2023 proposed regulations regarding the due diligence required to attest or certify that a clean vehicle battery does not violate the FEOC Restriction of section 30D(d)(7). The due diligence requirements require qualified manufacturers to trace the source of all ACMs and battery components to ensure they are FEOC-compliant.28 Treasury and the IRS declined to set a universal standard for how to comply with this requirement, despite requests for such guidance. The final regulations mirror the proposed regulations in requiring due diligence to "comply with standards of tracing for battery materials available in the industry."29 While this approach is relatively more ambiguous, it aligns with the expectation stated in the preamble (and requirement under the regulations) that qualified manufacturers will develop thorough tracing processes to confirm FEOC compliance, which will hopefully alleviate any uncertainty.

FEOC due diligence must also be sufficient for the qualified manufacturer to "know with reasonable certainty the provenance" of the ACMs, associated constituent materials, and battery components that are in the specified batteries.30 The final regulations, like the proposed regulations, allow a qualified manufacturer to meet this requirement through reasonable reliance on a supplier's attestation or certification that the relevant materials are FEOC-compliant, as long as the qualified manufacturer does not know or have reason to know that such documentation is incorrect.31 The final regulations broaden this reasonable reliance definition to include due diligence conducted by third-party manufacturers and suppliers.32 This expansion helps offset the lack of a reporting requirement that is directly imposed on upstream suppliers, which comments to the proposed regulations had requested. As a work around, qualified manufacturers may want to consider including terms in their contracts with suppliers that require reporting and tracing assurances regarding battery materials and battery components.

The final regulations also declined to adopt universal procedures for how qualified manufacturers should conduct FEOC due diligence (e.g., what happens if a supplier refuses to disclose proprietary information that the qualified manufacturer might need to confirm the accuracy of the supplier's attestation or certification?). Instead, as the preamble notes, the IRS prefers to address any issues that may arise from inaccurate attestations, certification, or documentation on the back end through the remedial avenues available under the regulations.33

In the short term, the risk that qualified manufacturers may experience a foot-fault with the due diligence process is somewhat ameliorated by the transition rule that excludes "impracticable-to-trace battery materials" from the due diligence requirements through 2026.34 This term replaces that of "non-traceable battery materials" in the proposed regulations in an effort to better describe the rationale of the rule: that some ACMs are currently impracticable to trace given current capabilities (and not to suggest that such ACMs cannot be traced at all). Nomenclature aside, the transition rule generally follows the framework that was outlined in the proposed regulations, such that qualified manufacturers may exclude impracticable-to-trace battery materials (and associated constituent materials) when determining whether a battery cell is FEOC-compliant.35

The final regulations are not entirely clear, however, on how to identify which battery materials are impracticable-to-trace. They define "impracticable-to-trace battery materials" as "specifically identified, low-value battery materials that originate from multiple sources and are commingled during refining, processing, or other production processes by suppliers to such a degree that the qualified manufacturer cannot, due to current industry practice, feasibly determine and attest to the origin of such battery materials."36 Further, such materials "have low value compared to the total value of the clean vehicle battery."37 (A number of comments asked for a de minimis threshold for low value, such as five or 10 percent, but the final regulations do not adopt this approach.) The final regulations go on to define "identified impracticable-to-trace battery materials" (emphasis added) as graphite contained in anode materials (an addition to the final regulations) and ACMs in electrolyte salts, electrolyte binders, and electrolyte additives.38 Frustratingly for taxpayers, the final regulations lack any description of how a battery material becomes "identified" as impractical-to-trace. The utility of the transition rules would be greatly enhanced by a framework for how such materials become "identified," and we welcome further guidance on this point.

While we wait, qualified manufacturers could consider seeking individual relief that a specific battery material is impracticable-to-trace through the up-front review process. All qualified manufacturers who want to take advantage of the transition rule must submit a report through the up-front review process (which is to include, among other things, a description of how the qualified manufacturer will comply with the due diligence tracing requirements once the transition rule is no longer in effect).39 It is anyone's guess as to how the IRS will respond to such a request, but it could be worth trying to expand the relief available under the transition rule.

The final regulations were more forthcoming with relief on how to track FEOC-compliant ACMs and associated constituent materials to each clean vehicle battery. The proposed regulations provided a temporary rule through 2026 whereby the available mass of ACMs and associated constituent materials could be allocated to battery cells manufactured or assembled in a facility without physical tracking, which was the general rule.40 The physical tracking rule could only work if supply chains were able to unravel the commingling of ACMs, however. Following comments about the challenges this presented and consultation with the DOE, Treasury and the IRS recognized that de-commingling was a hard task to complete by 2027. The final regulations therefore make permanent the allocation rule for ACMs and associated constituent materials.41 Unfortunately, the allocation rule does not apply to battery components, which must be physically tracked to specific battery cells.42 (If a qualified manufacturer was lucky enough to submit a periodic written report before May 6, 2024, there is a transition rule that alleviates the need to use physical tracking for determining that the relevant batteries and battery cells are FEOC-complaint.43)

In a win for fuel cell electric vehicle (FCEV) manufacturers, the final regulations confirm that FCEVs are exempt from the FEOC rules altogether.44 This outcome appropriately reflects how FCEVs are constructed, generally having only a small battery because they are primarily powered by a hydrogen fuel cell.

Effective Date and Reactions

The final regulations do not go into effect until July 5, 2024, 60 days after their publication in the Federal Register.45 Once effective, however, the final regulations apply for tax years ending after the date Treasury and IRS released the relevant proposed regulations, which in all cases is in 2023.46 Therefore, for calendar year taxpayers, the final regulations will be applicable for all of 2023. Treasury and IRS stated that this effective date was within their general rule making authority under section 7805(b)(1).47 That provision allows for final regulations to apply as of "the date on which any proposed or temporary regulation to which such final regulation relates was filed with the Federal Register," an exception to the general bar on retroactive regulations.

For more information, please contact:

Andy Howlett, ahowlett@milchev.com, 202-626-5821

Jim Gadwood, jgadwood@milchev.com, 202-626-1574

Jaclyn Roeing, jroeing@milchev.com, 202-626-5929

-----------

1Section 30D(d)(1)(3).

2Section 30D(e)(1). Vehicles that fail to meet this requirement will be eligible for a maximum credit of $3,750.

3Section 30D(e)(2). Vehicles that fail to meet this requirement will be eligible for a maximum credit of $3,750.

4Section 30D(d)(7)(A).

5Section 30D(d)(7)(B).

610 U.S.C. § 4872(d)(2).

7Treas. Reg. § 1.30D-5(e)(3).

8Treas. Reg. § 1.30D-5(e)(1), (2).

9Treas. Reg. § 1.30D-5(e)(1)(i). See also, Treas. Reg. § 1.30D-5(e)(5)(i), Ex. 1.

10Prop. Treas. Reg. § 1.30D-3(c)(17).

11Treas. Reg. § 1.30D-3(a)(3)(iii).

12Treas. Reg. § 1.30D-3(a)(3)(iv).

13Treas. Reg. § 1.30D-3(a)(4), (c)(1)(ii).

14Treas. Reg. § 1.30D-3(a)(8).

15Treas. Reg. § 1.30D-3(b)(1).

16Treas. Reg. § 1.30D-3(b)(3)(iii).

1789 Fed. Reg. at 37086.

1889 Fed. Reg. at 37080-81.

1989 Fed. Reg. at 37082, 85.

2089 Fed. Reg. at 37090.

2189 Fed. Reg. at 37082.

2289 Fed. Reg. at 37083.

2389 Fed. Reg. at 37090.

2488 Fed. Reg. at 84084.

2589 Fed. Reg. at 37084, 90.

2689 Fed. Reg. at 37084.

2789 Fed. Reg. at 37084.

28Treas. Reg. § 1.30D-6(b)(1).

29Treas. Reg. § 1.30D-6(b)(1).

30Treas. Reg. § 1.30D-6(b)(1).

31Treas. Reg. § 1.30D-6(b)(1).

32Treas. Reg. § 1.30D-6(b)(1), (c)(5).

33Treas. Reg. § 1.30D-6(f).

34Treas. Reg. § 1.30D-6(b)(2), (c)(3)(iii).

35Treas. Reg. § 1.30D-6(c)(3)(ii)

36Treas. Reg. § 1.30D-2(b)(25).

37Treas. Reg. § 1.30D-2(b)(25).

38Treas. Reg. § 1.30D-2(b)(26).

39Treas. Reg. § 1.30D-6(a)(2), (d)(2)(ii). Per the preamble to the final regulations, Treasury and the IRS anticipate issuing additional requirements for the transition rule report, including "robust documentation of efforts made to date to secure FEOC-compliant battery supply, such as potential suppliers engaged, offtake agreements, and contracts entered into with domestic or compliant suppliers."

40Prop. Treas. Reg. § 1.30D-6(c)(3)(ii)(A)

41Treas. Reg. § 1.30D-6(c)(1)(ii), (3)(ii).

42Treas. Reg. § 1.30D-6(c)(3)(i).

43Treas. Reg. § 1.30D-6(e)(1).

44Treas. Reg. § 1.30D-6(g).

4589 Fed. Reg. at 37706.

46See Treas. Reg. §§ 1.30D-1(d), -2(d), -4(j) (effective for tax years ending after December 4, 2023), -3(h) (effective for new clean vehicles placed in service after April 17, 2023, in taxable years ending after April 17, 2023), and 89 Fed. Reg. at 37744. Because the transferability rules do not apply until 2024, those regulations are effective for new clean vehicles placed in service after December 31, 2023, in taxable years ending after December 31, 2023. Treas. Reg. § 1.30D-5(k). The same effective date applies to the FEOC Restriction. Treas. Reg. § 1.30D-6(j).

4789 Fed. Reg. at 37743.

The information contained in this communication is not intended as legal advice or as an opinion on specific facts. This information is not intended to create, and receipt of it does not constitute, a lawyer-client relationship. For more information, please contact one of the senders or your existing Miller & Chevalier lawyer contact. The invitation to contact the firm and its lawyers is not to be construed as a solicitation for legal work. Any new lawyer-client relationship will be confirmed in writing.

This, and related communications, are protected by copyright laws and treaties. You may make a single copy for personal use. You may make copies for others, but not for commercial purposes. If you give a copy to anyone else, it must be in its original, unmodified form, and must include all attributions of authorship, copyright notices, and republication notices. Except as described above, it is unlawful to copy, republish, redistribute, and/or alter this presentation without prior written consent of the copyright holder.